My Combat Experience in Balete Pass

PFC Rodney C. Barrett

PFC Rodney C. Barrett

I have written this story because I have become aware that I am a survivor. Now as I wake in the morning, put in my partial plate, my hearing aids, put on my ankle braces, grab my walker, take my morning medicines, and waddle off to breakfast, I realize I am truly a survivor.

As I get older I, also, realize that those survivors of World War, II are gradually dying away ( or just fading away as they say).

Survivors of the Balete Pass are now few. When I got into combat in World War II, it had already wound down and some of the operations were called mop up. Oh how I dislike those words, mop up, it gives the idea that this operation was simple and not important. Still soldiers were being killed and injured, many had gone through maJor campaigns and were still corning face-to -face with the enemy.

Balete Pass was the last operation of the 25th Infantry Division in World War II. Still it was significantly important for clearing the Japanese from the island of Luzon.

Many of us were called boys, because of our 18 and 19 ages. Even today 18 year olds are still called boys, boys that have to become men quickly because of their task.

I praise God that my two sons did not have to become men in that way. However I do admire and appreciate those boys that had to become men so quickly to defend the freedoms we fought for in the World Wars. Especially those soldiers today who are now all volunteers. An infantry soldier or Marine infantry that has to come face-to-face with the enemy, regardless of the fire power and back-up they now have, still has the toughest task in any military involvement.

I would like to thank my wife of 46 years for helping me in writing this short story of my experiences in Balete Pass. She has been most helpful in proofreading, spelling correction, and limited knowledge of sentence and paragraph arranging. I am indeed a very fortunate survivor.

After finishing my basic training at Camp Roberts California as an infantry soldier, I was given an eight day "delay in route leave" before reporting to Fort Ord California in preparation to be sent overseas.

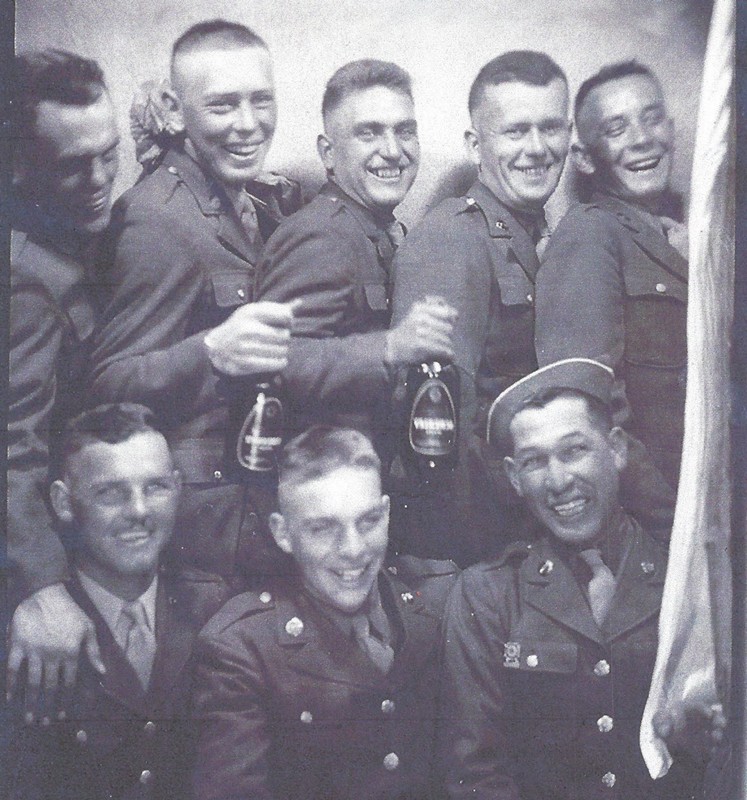

At Fort Ord we had a short period of training on safety precautions on board ship, which included learning where the life jackets and lifeboats were located and how to use them. Then we had to swim across a pool about a hundred feet in length. Crawl through and infiltration course with machine guns firing over our heads and small explosives going off around us to simulate combat. We were given haircuts (practically all of our hair was cut off). We were issued new uniforms, combat boots, a pack shovel, mess gear and the duffel bag to carry it all in. After we had finished this training, we were given a pass to go off base for one night before we were to leave for our ship.

The next day at Fort Ord we all had our last short arm inspection. From there we boarded a train to go to San Francisco, where our ship that was to take us to our theater of war was docked. We still weren't sure where that would be but we thought that, since we were leaving from the Pacific side, it would be somewhere in the Pacific theater.

The ship which we were loaded on was a new ship, manned by the Coast Guard. The captain had just been commissioned and this was his first ship to command. We sailed out of San Francisco Bay underneath the Golden Gate Bridge just as the sun was setting. As we sailed out away from the bridge, I stood on the deck looking at the bridge and wondering, if I would ever see it again. We crossed the Pacific without an escort. We zigzagged to avoid any kind of pattern that an enemy submarine could use in an attack.

The first land that we saw, after we left, was New Guinea. We anchored in a cove, where we sat for about a week and a half, waiting for instructions, I guess, as to where we would be taken.

None of the replacement soldiers went ashore but some of the crew took a shore-boat to do some kind of detail work ashore. After a day of anchoring there, some of the natives came out in their small canoes, they would dive for coins that the soldiers dropped in the water. Some of the soldiers threw ropes over the side of the ship, then the natives would tie bananas onto them to be hoisted on ship but that soon stopped by the captain saying that the soldiers could get sick from the bananas.

While we were anchored in this cove we spent most of our time above deck because it was quite warm. We were warned about getting sunburned and some did. The water was very clear and quite still.

It seemed to be a common sight for military planes in the area to practice diving on the ships anchored in the cove. There were several planes practicing diving on us as we sat anchored. We got quite use to it and we would wave as the planes dived on us. One day an open, double seated cockpit seaplane came over and dived on us, the pilot waved, we waved back (we thought it was unusual that a seaplane would dive like that because they are not attack planes). After a while he was back, this time he had a passenger in the second cockpit. Each time they dived they waved, we waved back. On about their fourth dive over our ship the plane failed to come out of its dive and crashed into the side of our ship, above the waterline. We all rushed to get to the rail to look down, all that we could see was a shadow of the plane sinking down into the clear water. The plane's engine went through the bulkhead. Several of the ship's crew were injured. There were whistles blowing, sirens going off and crew rushing all over the place. We were told to clear the decks and get back to our bunks. After the damage was assessed, we were told that we could return to the main deck. The plane had made a hole in the side of the ship, well above the waterline, close to the main deck. So here we sat in a cove off the mainland of New Guinea, a troopship loaded with soldiers, with a hole in its side.

The captain was very upset that he had a hole in the side of his new ship, which he had been commissioned to take out on its first mission, the damage caused by forces on his side. We sat there, anchored in the cove for another day, waiting to know what the captain would do with the ship. That night we could hear the anchor being lifted and the ship getting under way. He sailed to the Marianas Islands, where the repair was made in less than eight hours. We then sailed on toward our destination, which turned out to be the Philippines on the island of Luzon.

We arrived in the Philippines on the island of Luzon the last two weeks of April 1945 and were sent to a replacement camp where we were divided up and sent to different divisions as replacements to build our forces up to strength. On May 1st I was sent to replace soldiers in the 25th Infantry Division. The 25th Infantry Division was part of the Sixth Army whose mission was to push the Japanese Yamashita's forces out of Balete Pass in northern Luzon.

In the 25th Infantry Division I was sent to the 27th Regiment Company A. There were about 20 of us that were taken by trucks to Company A headquarters near the mountains. Where we left our duffel bags and filled our packs with one day of C rations, a shelter half, mess gear and shovel. Then we loaded our ammunition belts with ammunition and took 4 grenades (this was the first ammunition that I received since landing in the Philippines). We were told that our captain had made us all private first class and also that we were to receive combat badges.

We were then loaded into trucks again and taken to a stream where we were met by a sergeant that told us to fill our canteens and put the water purifying pills in them (we each had two canteens). He told us we were in a combat zone and could receive fire at any time and to be ready for an ambush.

We started up the stream not talking to each other but using hand signals to communicate. I could hear gunfire in the hills around us and a mortar shell going off occasionally (now I really knew l was in combat). Whenever we stopped to rest we would face opposite from the soldier in front of us so we could cover both sides of the trail, looking at the area in front of us, always looking for snipers. It was really hot and sweat soaked my fatigues as we climbed along the stream. I had a bath towel draped over my neck that I would pull out the ends of occasionally to wipe the sweat and salt from my face, I could feel the salt burning my eyes as it dripped down from my forehead. With so much sweat on my head my helmet slid around and often I had to shove it up to uncover my eyes. If I shoved it back too far, my pack would push it back again, leaving me continually trying to keep my eyes clear.

At one of the rest stops we were sitting facing the stream that trickled down some rocks making a very small waterfall, as we sat there we heard voices coming down the stream, they were very loud, we could tell that they were GIs. I wondered why they were so loud as I knew we were in a dangerous area. When they reached where I was sitting, they stopped to rest and, I learned that they were two soldiers being sent down to be sent home. They had enough points to be mustered out. They had been in three campaigns and now as the war was winding down, they had enough points to go home. What shocked me, as they were sitting there, was that they took their canteens, filled them from the falls and immediately drank some of the water without putting any of the water purifying pills in their canteens. I thought to myself, "They have been fighting so long they must feel nothing could kill them". When we moved further up the steam, there were three dead Japs with maggots all over them, lying right in the middle of the stream. I wondered if those two soldiers really would survive this war.

As we traveled up the trail, we met a woman with a child and a man with a rifle. The child was completely naked and had that puffed out stomach from malnutrition. I could not be sure whether they were Japanese or Filipino. Later I learned that the woman and child had been captured in a Jap cave. The army could not take civilian prisoners so the man was a Filipino guerrilla with a captured rifle taking them out of the combat area to turn them over to civilian authorities.

At this point I should explain something about these Filipino guerillas. Most of them were Filipino citizens. When the Japanese began to lose, these citizens banded together in small groups to help to run the Japs out of Luzon. They were poorly trained and lacked leadership. Some of the time they were a help but some of the time they were a hazard, which caused some casualties in our operation.

When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, some of them became involved with some of the Filipino women, even to having children together, creating a family. When we invaded the Philippines, some of the higher ranking Japanese retreated into the northern mountains, taking their families with them. Our forces had destroyed the big tanks and fighting equipment of the Japanese. The only fire power that the Japs in the mountains had was the small amount of guns and ammunition that they were able to take with them. We didn't have to worry about stepping on mines or being shelled by heavy artillery. The things that we did have to worry about were snipers, night infiltration, banzai charges (a suicidal charge by Japanese troops), and mortar shelling.

It took us about 4 hours to reach Company A's headquarters in the combat zone. We were all split up and spread into the four platoons of the company. Brownie (his last name was Brown, we called him Brownie) and I were put into the first squad of the first platoon.

The first squad was down to three men, a squad leader, an assistant squad leader and a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) man when Brownie and I joined them, our joining them made us a squad of five (a squad had eight men, when up to strength). We learned that positions in the squad were decided by seniority, so since Brownie and I were low men on the seniority list, we got to be first and second scouts, the most dangerous positions in the squad.

The Company had already formed their perimeter and our holes were already dug so I was told to stay in the hole with the assistant squad leader. I spent several nights in holes with this man, he had been through three campaigns, he was 37 years old and had never had a scratch. It was amazing how relaxed he was, he could sleep anywhere and at anytime. We stayed in our holes from dust to dawn, no communications with anyone around the perimeter. Each man in a hole had two hours watch while the other slept (if he could). The first night I looked over the terrain, noticing where every bush was placed and constantly checking to see that none of them moved, we were told the Japs sometimes camouflaged themselves with bushes to crawl up into our holes. I was not wishing to get that close to a Jap so whenever I thought I might have seen a movement I would try to wake up my buddy with a whisper "to look". But he never could be wakened, I had to sweat it out until I was sure it was nothing or thought it might be something, then I would take a grenade, pull the pin, count three seconds, throw it out and duck. (Our grenades had too long a fuse, if we did not hold it for three seconds a Jap might throw it back before it exploded). This did wake my buddy up, he would rise up, peer around a little bit, lay back down and continue to sleep. When it was my turn to sleep and I could get him awake, he would sit up and look around. I would then lay down and try to sleep but, when I opened my eyes and looked up, I could see his head bobbing. I slept very little at night.

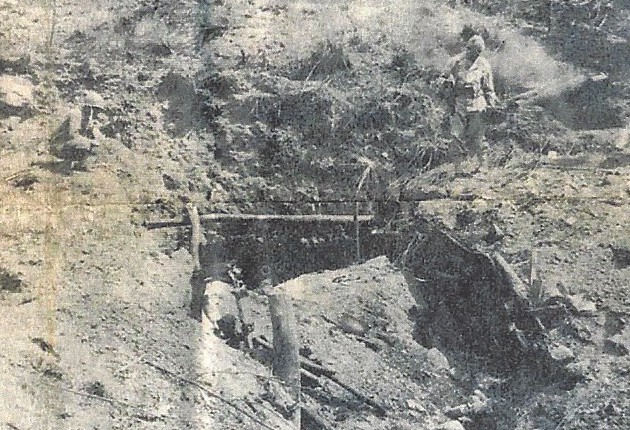

The tactics we used in this campaign to clean out the retreating Japanese forces from their dug-in placements in Balete Pass was to systematically move units of our forces through the pass, to engage the Japs in their holes or caves, and to set up perimeters on the high ground. When a unit (company or platoon) secured a hill or mountain, they would dig in, placing foxholes a few feet apart, around the edges of the hill. Other units were doing the same thing all across the pass. When a line of secure hills was formed across the pass, other units would move through these perimeters to take the high ground ahead of them. Each time a unit was to take a hill, they would move up into the secured perimeter ahead of them and get into the foxholes with the unit that had dug them, all of us taking cover together. Then the artillery would start shelling the terrain that we were going to take. When the shelling stopped, it was time for us to move out and make our push.

While the artillery shelled the area in front of us we could tell when they were about to stop (or hoped they would stop) as the shelling got closer and closer and the shrapnel flew overhead (this was done because, if there were any Japs in the shelling area, they would move up as close as they could get to our in-placement). So we always prayed that the artillery shelling would stop but not too soon or too late. When we got up to move out, the area around us looked much different, as the shelling cut down much of the trees and shrubs ahead of us. I wondered how anyone could survive out there after a shelling (I learned later that they could).

Each unit did not make a push every day and sometimes we did not have to dig a new foxhole for 3 or 4 days. We spent those days in our perimeters or on short patrols around the lower areas of the perimeter. During the day, if not on a patrol or watching for snipers (there were men on sniper guard during the light hours), we would try to make our perimeter more comfortable by taking C ration crates, tearing them up and laying the boards on the bottom of our foxholes, making them a little dryer area to lay on. When it rained, and it often did, we would try to cover our foxholes with our shelter halves to keep them dry. (A shelter half is one half of a pup tent, a pup tent is a two-man tent). We dug latrines (a narrow trench that you squatted over to dispose of your solid waste). We would mark them by placing branches on the ground around them and putting empty C ration cans on them so no one would step on this sacred ground. There were other things that we used the empty C ration cans for, sometimes we would take string and hang the empty cans together, then string them in the bushes around our perimeter so, if the Japs would crawl close to our perimeter, we would hear the cans rattle.

One day we made a perimeter on a hill where 3 of us had one hole, it was sprinkling so we covered our hole with shelter halves and limbs, then we tried to bail the water out that had sprinkled in, no matter how much we scooped up the water, there always seemed to be about two inches of water in the bottom of our hole. We crawled around checking our shelter halves to see how the water was getting in but found nothing that seemed to be leaking into our hole, then someone noticed bubbles coming up in one corner and realized that we had dug our hole in a small spring. We had to spend the night sitting in our helmets, hovering over a small fire of canned heat.

Our first patrol was the next day after we joined Company A. As we walked along this peninsula, there were about 22 of us, I was about in the middle of the column looking for Japs in the terrain around the peninsula. I had my first fears that the Japanese would see me before I saw them. Then we got word that there were Japs seen coming around the back of our column, we were told to stop and build up a perimeter and wait to see what to do. As I sat there trying to identify each soldier on my right and left so that no Jap could get between them and myself, I became so scared I began to vomit, the soldier on my left noticed this but could do nothing as we were expecting an attack. After about 20 minutes we got word that it might be a false alarm and to return to the company’s old perimeter. On the way back the soldier told the platoon sergeant that I was sick. As we moved back through Company B the sergeant told me to go to the Battalion Aid station to get something for my stomach. I went back to the Battalion Aid station, the corpsman gave me something for my stomach and told me to get back to my company before it got dark. I went back through Company B's perimeter, then I mistakenly started out down the same trail that we had gone on on our patrol and were told to return, as I lookedaround, I began to think the trail looked familiar and then I said to myself "They're all getting to look the same". I looked down and saw our communication line that we had strung out along that peninsula and had tied to a tree. The blood rushed to my head as I realized that I was back on the peninsula that we had come back from that day. I knew I had to get back over the trail. I ran, climbed, slid in the mud and thought that, if there were Japs out there, I would surely have to fight all by myself. Surprisingly my stomach was a lot better. It occurred to me that, when I came to the trail that I should have been on at Company B, I might be mistaken for a Jap. So, when I got back to Company B, I yelled my company name and that I was a G.I., fortunately I was met by a soldier of Company B holding his weapon on me and asking me what the hell I was doing out there. I explained that I had taken the wrong trail back to Company A. He pointed to the trail that I should have taken, shaking his head sympathetically. When I got back to my company, I reported to the company Captain, he looked at me as if I was some kind of nut and told me to spend the night in the squad leader's hole and not to do guard duty that night.

On the 18th of May 1945 my platoon was to take a hill in front of a machine gun nest of our heavy weapons emplacement. The squad that I was in was to lead the platoon. I was second scout and Brownie was first scout. Brownie was in the lead and I was behind him as we walked along the trail that led along the side of a dry ditch. We were moving just below this machine gun emplacement when someone from our machine gun nest started shouting about a Jap that they could see in front and to the side of us. Brownie and I squatted down and looked toward the dry ditch but could not see him. There was some argument about why they could not fire at him from the machine gun nest, something about not being able to get the machine gun down low enough. Sergeant Mahoney ran down to us and told Brownie to take a position nearer the dry ditch at the left and told me to go to a tree about 10ft. down the trail. I took the prone position alongside the tree, noticing that there were large tree roots to my left shoulder. Then Mahoney took a position between us about 3 to 5 ft. behind me. The BAR man took a position to my right about 6 ft. and about 5 ft. back. Mahoney threw a grenade toward the area that the machine gun nest was yelling that this Jap was in a hole, but none of us could see the Jap from where we were. After Mahoney threw the first grenade, they yelled, "A little further out", Mahoney threw a second grenade, then they yelled "About 5 ft. to the right". Then I heard Mahoney say, "What the hell is this, a ball game?" In front of me about 10 ft. down the trail I saw this head of a Jap looking up at the machine gun nest, he did not see me. It was my first to see a live Jap. I knew I had to shoot, I took aim and fired. The impact from my rifle knocked my helmet over my eyes, I had to push it back up to see if I had hit him. I knew I had hit him because I heard his helmet fly off and roll down the hill. Then I heard all of this yelling in Japanese and throwing the bolts on their rifles but I did not hear any firing from their direction. Then I heard a shot from my left, the Jap that Mahoney was trying to get had fired at me through the roots of this tree, evidently he could not see anything but my legs and was trying to hit me in the head. The bullet went through the roots of the tree, splattering wood slivers into the left side of my face and cutting through my GI jacket, through a towel that I had draped over my shoulder under my jacket and into my shoulder for about five or six inches long from the edge of my shoulder to about an inch from my neck. At the time I only knew that I had been hit. I turned back to tell Mahoney that I was hit, when I looked back, Mahoney's helmet was off, his head was lying back on a tree stump and blood was running down the side of his head and out of his ear. Then I heard someone whisper, "Mahoney is dead". I looked to the right and saw the BAR man wiggling back, I looked to the left and saw Brownie moving back as well and I thought, "They think I'm dead and they're leaving me." Just then someone from the machine gun nest shot off a phosphorous grenade from a rifle, I looked over my shoulder and saw the grenade flying in the air, the fins of the grenade hit a vine causing it to lose flight and drop down, right onto Brownie. He got up screaming and ran back, at that time I knew that I had to get up and run, fearing the Jap would notice he had not killed me and try again. But evidently he was running, too, so I got back to Brownie as our squad leader came running up and told us to build up the fire power while medics came down to get Brownie. The BAR man began firing into the terrain along this ditch and I began to fire my rifle as well. When the medic had Brownie on the stretcher, he was screaming and was in horrible pain, the medics gave him morphine and plasma, he was burnt from his ass down his legs to his knees and calves. The medics picked up Brownie and started carrying him back up the hill, we went back up the hill as well, firing down toward the area we were retreating from. When we got back up the hill with the rest of the platoon, the BAR man said, "I thought you were dead." I took off my shirt and he put sulfa on my wound and bandaged it with the packet that we all carried.

When Brownie was stable, the medics and I carried him back to an ambulance where we both were taken to a field hospital. At the field hospital they took the worst cases first so they admitted Brownie first and later, when I was admitted, I went to another tent. I did not see Brownie until the next day, he was in terrible shape, screaming and cursing because he was burned by our own grenade. They took him to a general hospital that day, I felt that he would make it. I learned, when I returned to my unit, that he had passed away from pneumonia.

I stayed in the field hospital for nine days, my wound looked pretty good but had not healed completely, the scab was still on my shoulder. The doctors said that I could return to my combat company. I returned to my combat company, every morning I had to go to the battalion aid station to have my wound dressed, they put sulfa and a clean bandage on it, however it became infected and would not heal so after six days in combat they sent me to the general hospital for one night and then I was sent to the rehab hospital. I spent about a month in the rehab hospital.

The rehab hospital was made up of tents. Each tent had about 10 army cots, the floors were dirt and at one end of the tent they had a small office, separated by a canvas drop cloth. Each office had a small desk that was used by the orderly who administered the drugs and did whatever the nurses directed him to do. The nurses went from tent to tent daily to look after the patients. We got our meals at the cook area which was covered by a canopy. We went in groups with our mess gear and ate wherever we could find a place to sit down. We washed our mess gear in large garbage cans, one with soapy water another with clear hot water for rinsing, then we swung them in the air to dry them. After breakfast and after lunch we were to return to our cots until after the nurses and orderlies came to each cot and the nurses gave instructions to the orderly and to us on what we should do to attend to our health problems (medications, exercises, washing, and cleaning).

I had some interesting experiences at the rehab hospital. One day after lunch we were all on our cots waiting for the nurse and orderly to come in to give us instructions, when two soldiers down the aisle got out of their cots, and were arguing about something (I'm not sure what). They stood up in the center of the aisle, nose to nose, getting ready to fight just as the nurse walked in with the orderly behind her, she realized what was about to happen and said, "You two soldiers get back on your cots and stay there." The soldier on her left returned to his cot but the other soldier said. "Make me!” She was carrying a clipboard in her right hand so she must have been left handed because she came around with her left fist and socked him on the left-side of his face, he went backwards, turned and grabbed the rails on his cot and let himself down on the cot. The nurse then said, "I want all soldiers in this tent to stay on their cots and not talk to anyone until I get back." She then turned to the orderly and they went back into the office where they had a conference and made a phone call. Then the orderly came in and told the soldier that had obeyed the nurse's instructions, to get his gear, he was to go to another tent. He then told the other soldier that he should apologize to the nurse because, if there was a hearing, he might be court-martialed. I imagine that nobody wanted a hearing because the nurse should not have hit him even, if he had disobeyed her order. When the nurse came back in, he told her he was sorry, she said that is all right, she had two brothers that she had to straighten out every once in awhile.

I stayed in this rehabilitation hospital for about a month before they said that I would be able to return to duty. By that time my outfit was out of combat and I was returned to my infantry unit, the 27th Regiment. They had set up camp and were training for the invasion of Japan. The 27th Regiment built a tent city some distance from an air station, it had only one building, a Quonset hut. The rest of the camp was made up of tents. Each company had its own area, with roadways and walkways marked off with rocks. We began our training for the invasion of Japan. We built our obstacle courses, net climbing areas, and a firing range. Everybody had some kind of routine duty. We trained in the morning and then the afternoon was spent in fixing up the camp. We had an outdoor movie area where special services showed movies at night and had church services on Sunday. I was lucky because they learned that I had played the saxophone in school so I was sent with two other guys in the regiment, one played the saxophone and the other played the piano, to this Quonset hut which had been made into the officers' club. They had instruments there that we could use so in the afternoons we practiced to play for the night movies. At night the piano was loaded into a truck and taken down to the movie site where we played familiar songs for the sing along before the movie was shown.

The war ended in August of 1945, that meant that we would not be invading Japan. We all were very happy and thought we were going home since the war was over in Europe and now in the Pacific but we were told that we were going to be in the occupation of Japan. Most of us had not given much thought to the occupation of Japan.

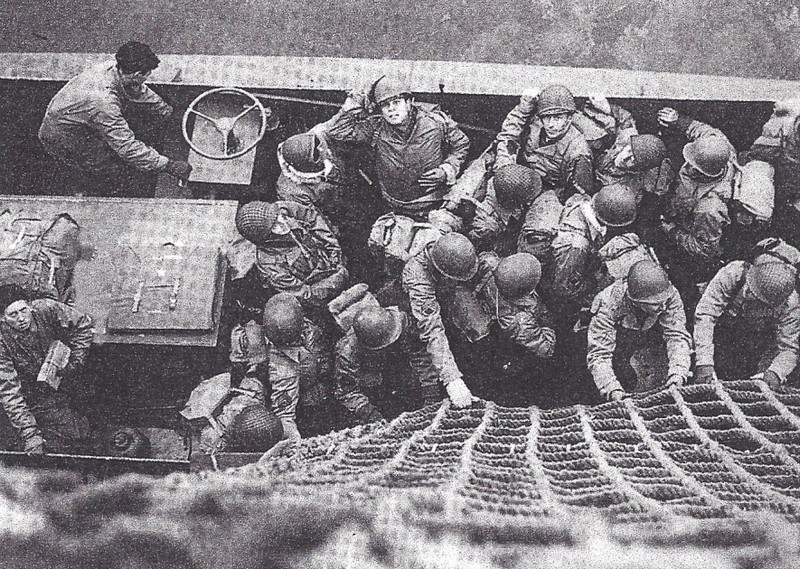

From the time Japan surrendered we prepared to break camp and get ready for the occupation of Japan. We were taken by train from the camp to the west coast of Luzon where we boarded landing crafts and were taken out to ships. We went from the landing craft and climbed aboard the ship. I can remember this because we had to carry our rifles, duffel bags and packs and climb up on nets to board the ships. It was hard to do, some lost their helmets, stepped on the heads of soldiers climbing below them, trying to hold on and climb with all of this was not easy. How thankful I was, when I neared the top of the net that a sailor grabbed me by the back of my jacket and pulled me the rest of the way up, it felt so good to know that I would not fall back into the landing craft. We boarded ships to sail for Japan on September 22, my 20th birthday. I was very sick that day and felt like I might vomit.

After we got settled in the hole, I asked the squad leader, if I could go up on the main deck and lay down, he said that I could. I went up on deck, lay down by the side of the rail, getting up from time to time to vomit and thinking what a hell of a way to celebrate my birthday.

We sailed the next morning, by that time I was feeling fine but most of the rest of the guys were getting sea sick. After we got to sea, we tried to sail around a typhoon but I think we got into most of it, it was a very rough trip.

October 29th we landed in Japan near the city of Nagoya. We unloaded onto a large landing craft by way of a large gangplank, so much easier than the way we got onto the ship. I need to tell you at this time that we had no ammunition, just our bayonets. They told us that we would be landing much like we would have done, if we had made the invasion. I looked around as we went in and saw all of these rocks to maneuver and thought what a hell of a place to make an invasion. When the landing craft maneuvered into a sandy beach area, it lowered its ramp and we marched off onto the sand, up an embankment to a street where we formed ranks and marched down this street for about six blocks. At each intersection a Japanese police officer was standing, facing away from us with his hands behind his back, I wondered, if he was trying to ignore us or protect us from something that might be coming at us. I also noticed children and women looking at us from the second story windows of the buildings. We then were loaded into trucks and taken to the mountains somewhere near to a Japanese airfield where we were to occupy and destroy its planes, however most of the planes had been destroyed by air attacks.

The extensive white routes shown on the map cover favorable terrain and were taken by the 26th in a matter of weeks. The much shorter yellow route up Highway 5 through Balete Pass took months!

Equipment I used in Balete Pass 1. Combat Boots 2. Helmet & Liner 3. Pack & Shovel 4. shirt 5. Cartridge belt 6. Canteen, cup & cover (I had two) 7. First aid pouch 8. Hand axe & carrier 9. Grenade carrier & Grenade. 10. Pants 11. M1 Rifle 12. Machete 13. Bayonet

The Japanese had occupied the Philippines for three years before we were able to liberate it. During the occupation by the Japanese the Filipino people had most of their resources taken from them to support the Japanese occupation forces. There were many Filipinos forced to work for them with little compensation.

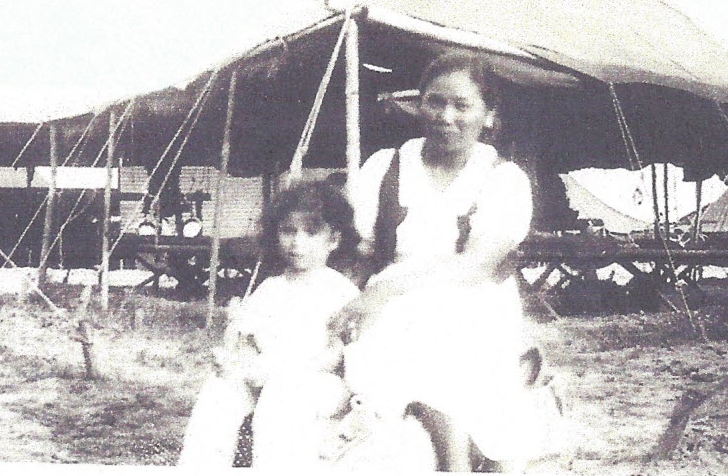

After the Filipinos were liberated they had a hard struggle to build up their lives, they were working hard to get back on their feet. This photograph is a photo of my laundry lady and her child. There were many women coming to our camp, taking our laundry to earn pesos for their families.

The little girl in the photo was very interested in me. When she came with her mother to pick up my laundry, she would sit on my cot and ask me questions, "Do you have any brothers or Sisters?", What do you do in the United States?", and so on. Of course she, also, enjoyed the peanuts and chewing gum that I always had for her. She was one of the lucky children, there were many children without mothers and fathers, they were left to beg for the leftovers from our chow line.

Message from the Author

May 18th 1945.

A day in my life that I thought I might forget, but never could, a day of fear, anger, hate, and sorrow, now I want to remember, and never forget to remember, those buddies who were with me on that day and never returned, as God graciously allowed me to. I often think of those two that lost their lives in that fire-fight I was in, often wondering what they may have become had they lived to the age God has allowed me to.

Sergeant Mahoney was on the island of Oahu, Hawaii when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. and he had fought in three campaigns, he was about to be sent back to the states as the war was winding down.

Private first class Brown (we called him Brownie, I never did learn his first name), was a replacement soldier like I was, fresh into combat. I was with him when he received the letter telling him he was a father, he was married on his last leave before being sent overseas, a son, who will never know his father.

Three Purple Hearts, two who gave so much. I will never forget them even though I knew them for such a very short time. Just one day in a war of many days, and many fire-fights with many sacrifices, this is a day I shall never forget.

Thank you for reading my story, I wrote it for my children, family, friends, and you.

Stories, like this short story, were part of history that were played out hundreds of thousands of times in the lives of men and women who defended our rights and liberties.

Today, when we demand so much, our rights and privileges, I wonder if we have given much thought to those that gave up those rights and privileges so that we could have them.

Again, thank you.

Rodney Barrett