My Life, My Story

by Bailey Gillespie

Korean War Veteran

I was captured and became a Prisoner of War on November 27th, 1950. I was released in the very last group on September 5th, 1953. I was held prisoner for 34 months, 1,013 days ... nearly three years.

In 1948 I was 18 years old and I joined the Army because there wasn't a whole lot to do at that time. They sent me to Japan. I signed up to be a medic because I decided I would rather tote a syringe than a rifle. I went to basic medical training school and lab school and then to a laboratory where I worked until the Korean War started. I was 20 years old when they sent me to Korea on July 10, 1950. When you're that young you don't know anything. In the beginning it was exciting to be in Korea. After the first day of battle it quit being exciting.

Another thing, when we were going from Japan over to Korea they issued us an M-1 rifle. Medics weren't supposed to have weapons, but they gave us one because the enemy didn't honor the Geneva Convention. We had already gotten reports that the North Koreans had wiped out General Dean's company in Taejon and then went in to the aid station and shot all of their wounded and the doctor. So, on that information we were issued rifles to protect ourselves. So we become riflemen and medics. I was promoted to sergeant in late summer 1950 as we advanced forward across Korea. I was sent back to Taejon to pick up supplies and returned just as we were getting ready to enter Seoul. Seoul was torn all to pieces. We were in a heavy fire fight and took a lot of wounded. We continued to move forward that fall until we were way up in North Korea. We received our Thanksgiving dinner on November 26th. After we ate we organized a spearhead, a company of men going forward on a reconnaissance mission. We travelled all that day and didn't see anything. That night we bedded down on the side of the road. About four or five o'clock in the morning on November 27th, the Chinese opened fire on us.

I was ordered to head back and set up an aid station to receive the wounded. I was in a 14-ton truck with canvas over the back with two South Koreans in the back with me. We hadn't gotten very far when we ran into the Chinese and they opened up on us. That canvas disappeared. I had a carbine that I had taken off a guy that didn't make it. I grabbed it and went out the back of the truck, hit the road and rolled over into a field. The field dropped down enough so there was some protection there, they couldn't see me. Being young and foolish, I stuck my head up to see what was going on and almost got it shot off. I saw five, maybe six Chinese come across the road into the field in front of me but there was a terrace between us. I was on the high side of the terrace and they were on the low side. One of them stuck his head up; he couldn't see me, but I could see him. I pulled the trigger on him. Another one stuck his head up and I pulled the trigger on him and his head snapped. I pulled the receiver back and snapped it again and again. Don't ask me why I wasn't being hit. I pulled an empty shell out and threw another round in and took care of the other guy. About that time, they threw a hand grenade toward me. That thing was spinning around like a top, sparks spewing out of it. I remembered from basic training that if you're ever that close to a grenade just stay flat. It goes up. If you get up you're going to get some shrapnel. It went off and four or five Chinese came over on me. We started fighting; they got beat up a little bit. Then one guy started trying to tie my hands behind my back but I refused to let him do it. If he had been a North Korean he'd probably have killed me. That's when I became a prisoner of war for the next 34 months.

We walked for nearly 10 days, up and over a mountain range, before we got to this valley. That was in December 1950. We left there about the middle of January to go back over to a town called Pyok Tong, North Korea, where they separated us into three groups: sergeants in one group, corporals on down in another, and then officers. I was a sergeant. By then the Chinese had taken over the camp from the North Koreans. If they hadn't, we would have died from starvation. We were freezing to death, too. It was often 30 degrees or more below zero and we didn't have adequate clothing or shoes or heat. Our beards grew real long and we had no way to wash or shave, and lice were all over us. One time they gave us pork to eat and it was full of worms and we refused to eat it.

How did you keep your sanity?

I don't know. You just have a different mindset then. You've got to accept things as they are, not as they way you'd like for them to be. If you start dwelling on things you could get in bad shape. At Camp 5, where I was, a lot of death was going on there. There were 20 a day or more, who died. A lot of them had delirium. One day I came down with dysentery. I had a real high fever and chills. The fever was so high I felt like I was delirious. As I lay there, burning up and freezing, I prayed for help. And then it seemed like I was lying in a grave in a tight coffin and people were looking down at me. I was struggling, but I could look up and see them. I was thinking, "I'm not supposed to be here." And then this bright light appeared at a distance and came toward me. It stopped at my feet. There were no words spoken ... but at that moment I started getting better, my dysentery stopped, my fever left and I got well. God appeared to me that night. I was sure God was with me. He saved my life. After all these years, 60 something years, I still get emotional.

What did you do for those 34 months?

We were busy. We had to do details and listen to lectures that went in one ear and right out the other. July of 1952 they put our company on barges and sent us down the Yalu River to a little place called Weawong and broke us down into three companies. The blacks and some whites were in one company; then company two and three. I was in two and it had all the United Nations forces in there. We had Turks, British, French and Australian. And we stayed there until the Armistice was signed, July 27th, 1953. I was released in the last group -- the last group -- on Sept. 5. When we got on the helicopter to leave, this major said to us, "You guys are really lucky." And I said, "Well, yes, I felt like if I ever got out of there we'd be liberated rather than repatriated." He said, "No, that's not what I mean. We did not have your names to be released until today." I don't think the Chinese were going to let us go. They had told us at one time that we'd be released according to how well we cooperated with them.

What brings you joy these days?

I get a lot of joy from my two great grandsons. One is 14 and his name is Hayden Bailey Pierce, and the other is nine, Chase Alexander Pierce. One was born on the 17th of November and the other on November 27th, the day I was taken prisoner. I remember that easily enough. The most meaningful thing is my family, knowing they are well taken care of. And it gives me joy to see people reading my book and becoming Christians and joining the church.

What are you most proud of?

I'm proud that God has let me live this long to be an example for others. And I had two brothers in World War II and I can trace my lineage back to the Revolutionary War. I joined the Sons of the American Revolution in September 2015.

What do you want your care team to know about you?

My wife is doing very well. She has a bad foot but luckily it's her left one. She still drives. We've been married for 62 years. If not for God and my wife, I would not be here. And the VA doctors at the VA medical Center, that's a true story.

What happened that put you in a wheelchair?

My feet were frozen really bad during the winters of '50 and '51. We were captured with summer clothes on and leather boots. Leather boots don't hold up to 60 degrees below zero weather.

What did you do after the war?

I started in the cafe business, but that didn't last very long. I wasn't cut out to be in the restaurant business. I considered going back in the service, but then I met my wife and she encouraged me not to. I finished high school and then went to Howard's Business College and the University of North Carolina in Raleigh on the GI bill. We were married and had a child while I was in school. I eventually went into textiles, in the design office. I was department supervisor of the cloth room for Fieldcrest Mill for 19 years, until it closed. We have one daughter, Christy Bailey Shires; one granddaughter, Summer Lee Pierce, and the two great grandsons.

Interviewed: Oct. 30, 2015 by Dr. Kelly

Transcription: Melanie Threlkeld McConnell

Also see Korean War Remembered: Prisoner of War, 1013 Days of "Hell," But for the Grace of God, Bailey Gillespie's memoir of the Korean War.

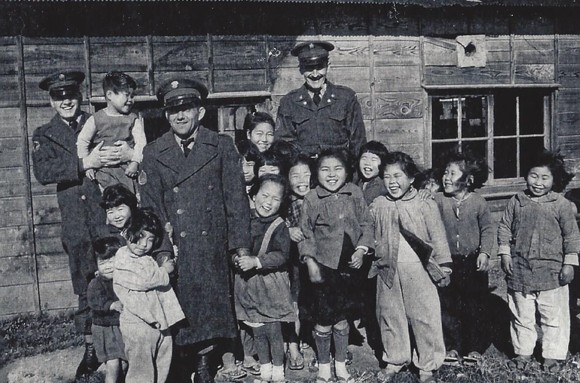

Bottom: Bailey Gillespie, Don Shore, Robert Arnett, James Mulkey