Wolfhound Commanders III: Al Hodges, A Wolfhound with Style

by Howard Landon McAllister

When old soldiers gather, a frequent question is, "Who was the best infantry battalion commander you ever knew?" For me the answer is easy. It was Al Hodges, who commanded the Second Wolfhounds from the middle of April until November of 1970, when the Colors of the battalion left Vietnam. His full name was Albert Pence Hodges. He was called "Al" by his friends. His family called him Sonny, but later I learned he didn't care much for the nickname. Certainly no one in the battalion used it, or even knew about it. I was his operations officer from the time he took command until I left the Wolfhounds to come home at the end of my tour in August. When we first met, I asked him how he wanted his name to appear on operations orders. His answer was what he didn't want, that is, to follow the standard Army format of first name and middle initial. I said, "How about A.P. Hodges?" I didn't add, "like A.P. Hill," but I was thinking it, since we had earlier been talking about Civil War battles and leaders. A slow smile crossed his face, as he read my mind. "Yeah, A.P. Hodges will do it."

Among my reasons for saying he was the best was an ability that helped make him an outstanding commander. He could listen to information from a variety of sources at the same time, process it instantly, make a decision quickly, and then smoothly issue an order in his calm, Southern way of speaking. But he was not slow in action. At his urging, the battalion would fly into action like a coiled spring, and it was all the staff could do to keep up. For an operations officer, it was the stuff of dreams. But he always had the knack of staying calm and projecting it to the men around him, no matter how dangerous the time or place. Time after time, he would stand up and coolly look around in the presence of enemy snipers. In May of 1970, when we were in Cambodia, one of the company first sergeants told me, "Major, that colonel acts like he is bulletproof -- or invisible!" Hodges had come to the battalion immediately after the battle in the Renegade Woods, our last big fight in the Vietnam War, and he had to hit the ground running, since we were planning the Cambodia operation. There was much to do and little time to do it.

Major Bob Farmer was the executive officer, and I was the operations officer. Captain Jim Grimsley, formerly General Hollis's aide, had joined us, understudying my old comrade, Captain Dick Eye as assistant S-3. Captain Paul Evans, formerly commander of Company D, was the intelligence officer. Captain Clarence "Mert" Agena was the artillery liaison officer and fire support coordinator, whose radio commands set the howitzers to firing in support of Wolfhounds in action on the ground. We were a competent team, and with four companies of Wolfhound riflemen, we believed we could do anything we were ordered to do.

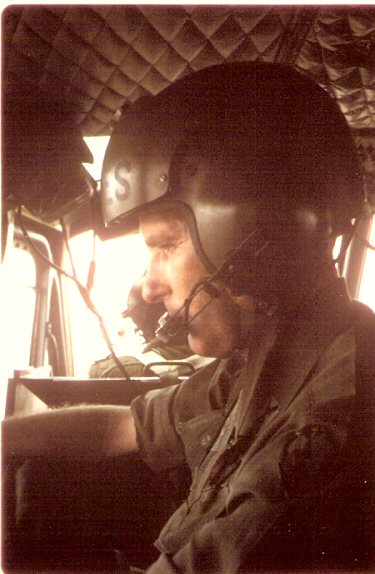

From a helicopter, Lieutenant Colonel Al Hodges watches one of

his rifle companies air assault into Cambodia on May 11, 1970

(photo property of the author)

Cambodia turned out to be mostly a non-event. The operation that should have provided a highly skilled battalion commander like Al Hodges with a colorful campaign in a new war zone was anticlimactic. He was ready, and his battalion was ready, trained to a fine edge, and fresh from hammering the enemy in the Renegade Woods. But only one company saw any action worth mentioning. Bravo Company, under command of Ed Criswell, a hero of the Renegades, met the enemy soon after the battalion landed in an air assault on May 11. The valiant Criswell, who would be wounded and out of the war within a month, was itching for a fight that never materialized. Lieutenant Dennis Heitner, leader of Bravo Company's first platoon, described the action in a letter home:

14 May 70

...We airmobiled into the "fish-hook" (15 clicks into Cambodia. 4 lifts of 16 helicopters each time. Wolfhounds and 4 other battalions of the 3rd Brigade. My platoon was point for movement into the jungle & we got shot at the first afternoon from our right front. I called in a dustoff for one of my men-wounded in the stomach & 3 other men—heat casualties. Our artillery forward observer got shot in the knee. He only had 36 days left in country.

That night we had 7 POWs come up & give up @ our AP site. So we bound them & had to keep them all night. Needless to say, we didn't get much sleep. Our CP got penetrated w/4 NVA in the perimeter. Our company killed 5 & lost 1 killed & 1 wounded. Our captain set it up really stupid - In a valley, they dug 2 man positions 20 meters apart in a circle & in the daytime, w/ only2 dozen men. It's a wonder only 1 man was killed.

Next day we found a base camp – duplicating machines, tape recorder, medical supplies, food, clothing, etc., ammo, rockets, weapons.

Another group found VIP headquarters – limousines, real ritzy houses, trucks, a tank, etc.

This morning we got flown out of Cambodia back to Vietnam – Fire Base Frances (Right on Saigon River) Everybody went swimming this afternoon & shaved off their beards. I kept on my "Cambodia mustache" for the fun of it.

We'll be out in the woods tonite in a company sized perimeter. Sure hope we get back to Cu Chi soon.

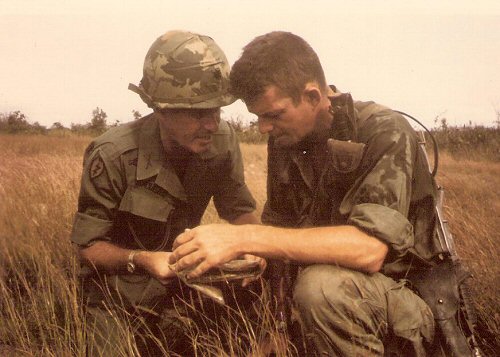

Lieutenant Colonel Al Hodges confers with bareheaded Captain Ed Criswell, one of his

company commanders during the fighting in Cambodia in May, 1970 (photo property of the author)

The Cambodian adventure was over for the Second Wolfhounds. Lieutenant Heitner soon got his wish to get back to Cu Chi, and wrote home again from there on May 27, with anniversary wishes for his parents in Cincinnati, OH. They would receive only three more letters from him, the last dated June 11. Heitner was killed while on an ambush patrol on June 13.

I was with Colonel Hodges when he signed a letter expressing his sympathy to Heitner's parents. The lieutenant had been one of the officers decorated for gallantry in the Renegade Woods, and the battalion commander had decided to keep an eye on him for early advancement, possibly even company command. As he handed the signed letter to the adjutant, he looked over at me and said, "Get your hat. We're goin' flying." I had already learned It was his way of displacing the regret he felt about our casualties.

"Going flying" meant getting one of the hotshot loach pilots of 3d Brigade to buzz a few likely spots that might conceal enemy soldiers as we were on our way to visit one of the companies at a field location. The pilots thought it was great fun. The colonel sat in front, beside the pilot, and I always sat in back of the tiny helicopters, which had all of the doors removed. I kept my Car-15 at the ready, and I had a claymore bag of filled magazines on the seat beside me. He held a bag of hand grenades on his lap. My job was to cover him, if we spotted any enemy, while he threw grenades. Only once did we spot a VC, ducking into a camouflaged hole beside a bomb crater. The pilot dived on the site, the colonel readied his grenade, and I leaned out to spray the area. When I pulled the trigger, nothing happened. The pilot pulled pitch quickly and got us out there, and the colonel looked daggers back over his shoulder at me.

Lieutenant Colonel Al Hodges in a loach leaving a helipad at Cu Chi. The mission was not "goin' flying"

as described in the text, since no one was riding "shotgun" in the rear seat (photo property of the author)

When we got back to Cu Chi, I disassembled the weapon, and as I suspected, the firing pin was broken. Colonel Hodges never brought the matter up, but I made sure to test-fire the Car-15 before we went flying after that. It was the only time the reliable little weapon failed to fire in that whole tour of duty.

After Cambodia, the war was winding down for us. During that period of time, the battalion area of operations was the size of the whole AO of the 3d Brigade of pre-Cambodia days. We had companies all over the map in the area around Cu Chi, so it was also a busy time. But I remember a couple of brief, pleasant interludes at Cu Chi with time out for a few pleasures almost like those of home.

One day, Colonel Hodges nudged Bob Farmer while Bob and I were in a conversation, saying, "Let's go to lunch, boys." When we walked out of the headquarters and turned toward the mess hall, the colonel said, "We're going to my place," motioning toward his quarters. That day we had something that came as close to a stateside hamburger as anything I ever had in Vietnam. Afterward, Bob and I always called it a "Big Hodge." The colonel had his own recipe and accepted no shortcuts or changes in assembling the burgers. If I remember correctly, tomato was a forbidden ingredient in a "Big Hodge." The duty schedule prevented us from enjoying the treat very often, but I never forgot it, and I am certain that Bob has not.

My time to return home was mid-August, and, as the time approached, the days passed in a blur. Spending more time in Cu Chi base camp meant greater opportunities for Wolfhounds to get into petty trouble, with readily available alcohol and other diversions. The colonel was not a severe disciplinarian, and he believed the chain of command worked both ways. He established a discussion group he called the "Wolfhound Council," and every company was represented on it, with men in the lowest ranks, as well as the leaders. Some of the company commanders weren't sold on the idea, but it helped identify problems we were able to nip in the bud, before they became serious. But the colonel was no patsy, and he didn't just transfer the chronic foul-ups out the way some commanders did. They were transferred out of the battalion, but it wasn't that simple. The Hodges solution for a man who couldn't cut it in the Second Wolfhounds was, as he put it, "slick of sleeve, empty of pocket—and gone."

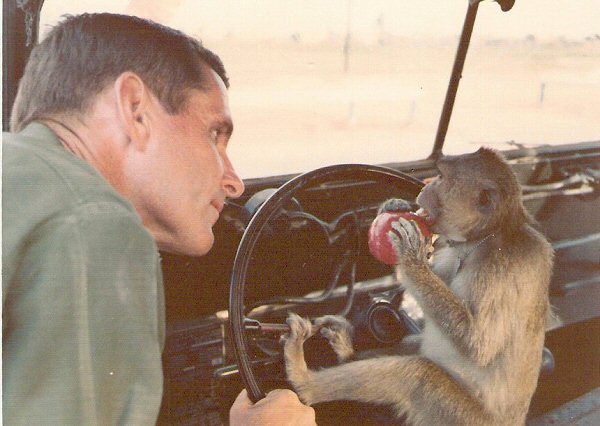

He loved the camaraderie of an infantry unit, as most old soldiers do. He recognized the importance of morale and its fragility in a war setting so far from home. His appearance was always as impeccable as circumstances would permit, but he was no stuffed shirt. When the battalion returned from Cambodia, a collection of monkeys appeared in the units. Soldiers went out of their way to justify the retention of the new mascots. The drivers in the battalion headquarters advanced the theory that the simians would make good vehicle guards. The monkeys certainly loved camping in the jeeps, where they fattened on the giant red apples flown in often from the west coast of the United States. The colonel listened to everything the men had to say and observed the monkeys in their new habitat. He could ham it up with the best of them, and he even posed for pictures with one of the monkeys perched on his shoulder. Finally he approved, after specifying that the animals had to be taken to the Division veterinarian for health checks and shots. And the monkeys joined the dogs as Wolfhound companions at Cu Chi.

The CO studies the monkey used by his driver as a vehicle guard. The monkey seems

to be more interested in lunch than guard duty (photo property of the author)

He wasn't much for short-timer attitudes. If I didn't know it already, I learned it on the day I left the Division. I thought I had said my good-byes the night before, so my plan was to sleep in, have a leisurely breakfast, and then go down to Long Binh for outprocessing. It didn't turn out exactly like that.

About 7 a.m. I awoke to see my battalion commander, helmet and web gear on, with that damn bag of grenades in his hand.

"Get your ass out of bed," he said, "We're going on a village seal," meaning a seal-and-search operation. It was a type of operation we conducted with Vietnamese units to round up enemy soldiers being harbored in villages in our AO. The Vietnamese also got the added benefit of catching deserters from their own army.

"Colonel, I have already turned in my TA-50 gear," I said. "I don't even have a weapon."

"Don't tell me your story, Major," he grinned as he walked out.

I dressed hurriedly, went to the supply room, checked out my old flak jacket and web gear, my steel, my Car- 15, and ten loaded magazines, and headed for the helipad.

I don't remember which company of ours went on the seal, or much else about it except that it was uneventful. I think the Vietnamese bagged a couple of deserters.

When we got back to Cu Chi, I turned in my gear, picked up my bags and walked to my jeep. As the driver and I rolled down the road toward Long Binh, I didn't even look back.

The colonel commanded the Second Wolfhounds until the battalion left Vietnam in November 1970.

We served together again briefly at the National War College in 1973-74. I went on to graduate school, and he went back to Vietnam. He was there when the last Americans left in 1975. A couple of years later, when I was chief of the Army News Service, I saw him when he was in a pressure-cooker operations assignment in the Pentagon. He retired as a full colonel some time after that, but when I think of him, my mind goes back to our days in the Wolfhounds. I will always remember him as the best infantry battalion commander I ever served with -- bar none.

© Copyright 2006, Howard Landon McAllister