Bad Day at Bo Bo Canal, Part II: Hindsight

by Howard Landon McAllister

by Howard Landon McAllister

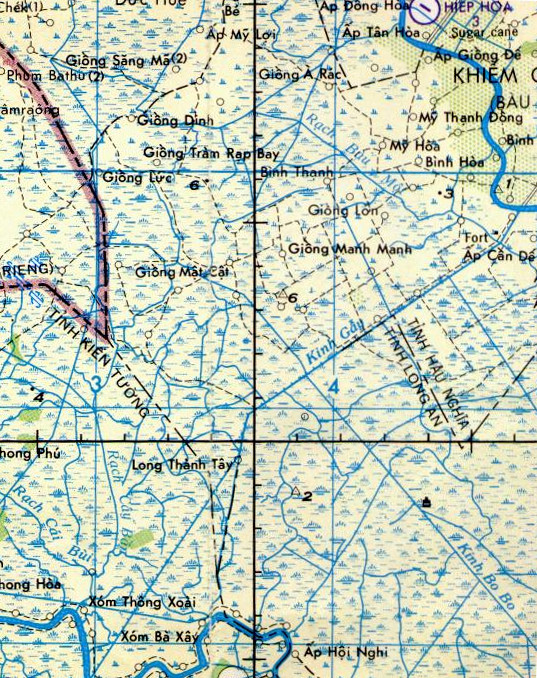

Jutting into Vietnam, the terrain near the southern tip of Cambodia may be among the most forbidding landscapes on earth. Wolfhounds called the tip Parrot’s Beak. Canals, swamps, and marshes without end, with narrow strips of land alongside, are how American soldiers in the Vietnam War remember that area. Heat from a tropical sun, torrential rains, and wild temperature swings from day to night--along with pestilent insects and snakes--combine to create a world rivaling the worst penal colonies described in any literature. A major waterway nearly 15 miles in length, the Bo Bo Canal intersects with another long canal called the Gay, which leads to the Vam Co Dong River west of the city of Duc Hoa.

Fighting in that kind of environment is tough, and it calls on every survival instinct that soldiers can muster to stay alive. When the Second Wolfhounds went into the area on July 29, 1969, their mission was the emergency relief of Special Forces Detachment A-326, 5th Special Forces Group, commanded by Captain James Joseph Amendola.

Other than sparsely-detailed official accounts, and information gleaned from and about the Rittgers tape published earlier in these pages, little has been written by the soldiers who survived that combat. The day had its heroes and victims. First Lieutenant David A. Brown, an irreverent Kansan with experience as a platoon leader and a flair for tactical inventiveness, was the chief reason the Wolfhounds avoided even more casualties in the fighting. Other Wolfhounds lost their lives or were crippled in body or mind by the events of that day. One soldier’s heroism was not officially recognized until many years later, and there may be others who continue to go unrecognized.

The situation of the Special Forces detachment was already beyond recovery when the Wolfhounds arrived on the scene. But Lieutenant Colonel Rittgers had no way of knowing this from a helicopter in the air. After he received word that Captain Kotrc, the commander of Company D had been killed, the battalion commander decided to do his job on the ground, where he could properly assess the situation.

When he landed, Rittgers was met by Colonel Maddox, his brigade commander. Later, Rittgers would comment, “We exchanged no words. He merely pointed to the direction of the enemy. That’s what I would call a mission type order in its briefest and clearest sense.”

Rittgers had ordered Company C under Captain Bruce Languanet to land to the east of the area of known enemy activity. Before the unit had traveled a hundred yards, it was exchanging fire with the enemy. Languanet was among the first to die, along with Specialist Four Larry Lynn Riddle, Private First Class John Edwin Hisey, and Private First Class Joseph Peter Reubel.

Staff Sergeant Stephen Donald Gleckler, from the battalion S-3 section, who had grabbed his rifle and climbed aboard a helicopter carrying Company D Wolfhounds, was also shot down. No one remembers if Gleckler was sent on the mission or went on his own to assist the company, which was short-handed on officers and NCOs at the time.

Movement in the two companies stalled. As described earlier in part I, the situation continued to worsen when Rittgers and others were wounded, and more Wolfhounds died from enemy fire.

Specialist Four Carlos M. Saladino, whose M60 machinegun anchored the right flank of Company D, remembers seeing Lieutenant Colonel Rittgers and Lieutenant Thompson moving near him shortly before their life-and-death struggle in a water-filled crater.

Lieutenant Dave Brown’s courage and leadership got them out of a bad spot. Aware that Kotrc had been killed and Company D was without a commander, Languanet sent Brown to take command. Shortly after that, Languanet was himself killed. Brown was able to get control of the situation and have the wounded evacuated, including the badly-wounded platoon leader, Thompson, who was carried to safety under fire by Sergeant David A. Reynolds and Private First Class Paul J. Wedlock of Company D. Rittgers’s struggle in a water-filled bomb crater, along with that of Thompson and an enemy soldier, had ended when the enraged battalion commander battered the enemy soldier to death with a steel helmet.

The final event in the Bo Bo Canal story would not take place until August 21, 2009, when Paul Wedlock, a quiet, reserved Pennsylvanian known to former Wolfhound friends as “Wedge,” received a Silver Star medal for his heroism so many years ago. At Wedlock’s award ceremony, retired Colonel Rittgers described Wedlock’s action this way:

“A medical evacuation helicopter was finally able to land some distance away, but because of the heavy enemy fire, it seemed like an impossible task to get Thompson to the helicopter. Then, unexpectedly, two soldiers moved from their protected positions to our bomb crater, provided emergency first aid, pulled Thompson from the crater, loaded him onto a makeshift stretcher and dragged him to the waiting helicopter—all of this while under enemy fire. One of these soldiers was Paul Wedlock. No one sent them. They simply responded to their military training, saw what needed to be done, and did it that they would be risking their own lives.”

The gallantry of some of the men who fought at the Bo Bo Canal was recognized and honored soon after the fighting. Sergeant Dave Reynolds, who worked with Wedlock to carry Thompson to safety, was awarded the Silver Star shortly after the action, along with a number of others. Wedlock’s recognition did not come for many years, and some soldiers who deserved awards went unrecognized. The confusion of the battlefield is a poor environment for recording events. It happened over and over in that war, as in others. Before information could be gathered and reports could be written, the battalion and companies were fighting in other battles. The story of the Bo Bo Canal faded into obscurity and legend—a thread in the fabric of our military history.

Some of the questions regarding the fighting were answered in a paper written in 2006 by Texan Freddie M. Ballard. His writing was intended to provide information about his long-ago war for his grandchildren. Ballard was a 19-year-old rifleman when he arrived in Vietnam. Later he was given the choice of becoming a M79 grenadier or a radio-telephone operator. He describes his decision:

“I loved to fire the M79, but the requirement to carry seventy-five pounds of ammunition in combat made my decision fairly simple.” He would carry a radio and a M16 rifle.

Later he was a radio-telephone operator for Captain Kotrc, the company commander, and on July 29, he had to deal personally with the perennial question of radio operators, “Sir, if you get hit, who is in charge?”

Often, the answer was, “You are—for a while.”

Ballard recalls that the landing zone was not under enemy fire, and the company moved quickly, trying to locate the embattled Special Forces unit. As the company moved alongside the Bo Bo Canal, they came under intense enemy fire from well-concealed positions, and the unit quickly went to ground. Ballard tried to return fire with his rifle, but the barrel had become obstructed, and it exploded. He was able to pick up a rifle dropped by a dead or wounded soldier, and he returned fire with it.

The company continued to take casualties, while Captain Kotrc tried to coordinate fire support from the Cobra helicopters above the battlefield. The company commander and Ballard were joined by others. Ballard described the death of medic Kris Shaw, killed while rendering aid to a wounded man. Others were killed or wounded, including the company commander.

“Suddenly a Chi-Com hand grenade landed directly on Captain Kotrc … I grabbed Captain Kotrc and rolled him over. The first thing I saw was a massive chest wound,” said Ballard.

Kotrc was dead. Ballard removed the mimeographed radio code book from Kotrc’s jacket pocket, and he was able to establish radio contact with a command and control helicopter above. Ballard cannot identify the contact, but it seems likely that it was either the battalion S-3 or the brigade commander, both of whom were overhead during the engagement.

As in so many other engagements in the war, the enemy activity was hit and run, and they disappeared. When the firing had ceased, Ballard received a radio call from “Killer,” the company’s artillery forward observer. As he looked at the dead and wounded alongside the canal, Ballard suddenly saw the forward observer a short distance away, while they were still speaking on the radio. They were close enough to each other to speak without radios. It was then and is now a symbol of the confusion of war.

The Bo Bo Canal—long ago and far away.

Copyright 2010 by Howard Landon McAllister