Editor's Note

When I started writing this article, it was my intention to find the single best example of Wolfhound company commanders in the Vietnam War. It was a challenge. When I thought about Chuck Penn, Ed Criswell, Paul Evans and other great company commanders I had known in the Second Wolfhounds in 1969-1970, I knew it would not be easy, perhaps not even possible. There were commanders in two battalions to consider, and five years of war experiences to cover. At a minimum, at least a hundred officers would have to be considered. That being said, Wolfhounds are hardheaded, and I am no exception. At length, based on years of research, I am still not satisfied that I have an answer to the question. However, I do have an opinion, and here it is. If any single infantry officer from the Vietnam War fills the bill, it is Captain Robert P. Garrett. Here is his Wolfhound story.

Wolfhound Company Commanders I: Captain Bob Garrett

by Howard Landon McAllister

Infantry company commanders are leaders, and their jobs are about leadership—first and last. Some of the best writing about company level military leadership was done after the Vietnam War by the late Colonel Dandridge “Mike” Malone. His experience in Vietnam exposed a stark truth, and he wrote about it convincingly. Malone believed there is no truly adequate preparation of junior leaders for the crucible of combat. The lessons have to be learned over and over, in each new war and by each new generation, in preparation for the conflicts of their day. Malone knew that the Army made every effort to provide a doctrinal framework that would prepare all of its leaders, junior and senior, for war, but he also knew that many of the Army’s good intentions got lost in translation. Malone had a genius for presenting Army doctrine in words ordinary soldiers could understand easily, in words they could live by. His 1983 book, Small Unit Leadership, is a valuable tool in development of junior leaders in the Army. Some of Malone’s words may prove to be timeless. His definition of military leadership itself is a powerful example:

“The very essence of leadership is its purpose. And the purpose of leadership is to accomplish a task. That is what leadership does—and what it does is more important than what it is or how it works.”

Malone liked to use simple, direct language. As he put it, the Army’s war doctrine has distinct roles for leaders at various levels: generals concentrate forces; colonels direct battles; captains fight. There is no better example of a fighting company commander than Robert P. Garrett.

Bob Garrett commanded two companies in the First Wolfhounds in 1966. He was in command of the headquarters company when the Wolfhounds went to Vietnam from Hawaii in early 1966. Headquarters companies are essential military units, but it is not usual for them to be in direct combat as units. When warriors are in command of them, they usually look for the first opportunity to get command of a rifle company. Bob Garrett was no exception. He wanted a fighting company and he got one. He commanded Company B of the First Wolfhounds from April 3, 1966, until the end of his tour. His nine-month tenure in command coincided with a critical period in the war. From first to last, it was a test of his leadership, and he left a solid record of achievement.

Nothing points to the quality of leadership in the unit better than a low casualty rate. During the time Garrett commanded the unit, the company’s number of men killed or wounded in combat was far lower than in any of the other companies, with an equal exposure to combat among all of the units. Company B had a total of ten men killed in action while Garrett was in command. Another rifle company in the battalion lost more men on a single bloody day in July. While direct comparisons cannot be made, good company commanders rightly gain a reputation for stinginess with their soldiers’ lives.

With characteristic modesty, Garrett assigns the credit for the company’s record—including the low casualties--to his outstanding noncommissioned officers, but his battalion commanders remember his performance in Operation Attleboro and other fighting.

"He was one of the two coolest officers I ever knew under fire,” recalls Maj. Gen. Sandy Meloy, whose record as the legendary Mustang 6, commander of the First Wolfhounds, needs no embellishment. Meloy’s reputation was established during Operation Attleboro in the first days of November 1966, as described in these pages and elsewhere. Meloy had commanded the battalion for four months before that crucial action, with ample opportunity to gauge Garrett’s mettle.

Brig. Gen. Harley F. Mooney, whose own record as an outstanding rifle company commander in combat dates from the Korean War, describes Garrett in powerful terms. “Bob was as good as they come,” said Mooney in a letter to the author. Mooney himself is remembered as the battalion commander who helped turn the First Wolfhounds into a fighting unit after an uncertain start in Vietnam. Mooney was the only officer to command both of the Wolfhound battalions in combat in Vietnam in early 1966.

In the First Wolfhounds, as in most other infantry battalions, one of the rifle companies sometimes gets a reputation as the “hard luck” company. In the first half of 1966, that unit was Company A, which had suffered many booby-trap casualties in the early “clearing” operations near the Cu Chi base camp. It was a reputation not turned around until later in the year, when Captain Richard Cole, a West Pointer with solid leadership skills, took command before Operation Attleboro.

On July 19, the hard luck had continued for Company A. The company was conducting Eagle Flights with individual platoons. The first and third platoons of the company had become heavily engaged with the enemy, at locations too far apart to support each other. The remaining second platoon of the company was inserted to support the first platoon. The fighting continued, and the two platoons took very heavy casualties. For whatever reason, there was little effective artillery fire support. At the end of the day, the remnants of the two platoons had to be extracted under fire. The annihilation of the two platoons was prevented only by the protective response of helicopter gunships and their subsequent extraction under fire.

The third platoon of Company A took a number of casualties, but the unit was spared from taking more by the quick response of Captain Garrett, who landed with one of his platoons. In the initial fighting, all of the radios in the A Company third platoon were damaged beyond use. When the ability to communicate with the platoon was lost, the battalion commander ordered Garrett to go to the relief of the platoon from his company’s location at Trang Bang.

Garrett describes the action:

“I was told one platoon of A Company was pinned down with many casualties. My orders were to secure the area, treat the wounded, and inflict as much damage as possible on the enemy. Then I was to extract all personnel from the location.”

Accompanying his second platoon under Lieutenant Ashcraft and Sergeant MacAngus, Garrett and his command group went in. After the platoon had swept through a wood line adjacent to the LZ to clear the area of VC, the wounded were collected and moved to the LZ for evacuation.

“Most of them were spread from the LZ to near the wood line, “Garrett said. He remembered that both the platoon leader and platoon sergeant had been wounded.

After the A Company men had been evacuated, Garrett ordered a pre-extraction sweep inside the wood line. After determining that the enemy had quit the area, the B Company element was extracted under cover of gun ships and returned to Trang Bang.

The quick response by B Company was the only bright spot in a dismal day.

Company B gained proficiency in the summer of 1966 under Garrett. During that time, the area around Cu Chi was disputed ground, and it was not uncommon for the division headquarters to come under mortar fire. After one such incident, Garrett was ordered to conduct an air assault into an LZ not far from the suspected mortar site. A sweep soon located the mortar site, which had been abandoned by the enemy at the approach of Company B. Mortar pits were located, with aiming stakes perfectly aligned with the flagpoles in front of the 25th Division headquarters.

Although the mortars were not located that day, the rapid response displayed by Company B that day set a precedent. It was one that established a pattern of response that greatly reduced the number of fire incidents on the base camp. As his unit made its way back to the camp, Garrett demonstrated another skill that would reap benefits for others in future operations. As he moved his unit through an area that had become known for the frequency of sniper and booby trap casualties, he used artillery support in covering his unit’s movements, and he used it well. It is an essential skill for small unit commanders, but it is also one that requires training, care, and foresight. On this occasion, Garrett’s handling of his unit came to the notice of Maj. Gen. Fred Weyand, the division commander. Company B had been the first unit to pass through that hostile area without taking casualties.

On 29 August, Garrett and several of his leaders would be wounded, one fatally, in a hostile area in the Trang Bang District north of a fire support base called Kansas City. The area, which would be named the "Citadel" by the Wolfhound battalion commander, was a maze of enemy tunnels artfully concealed under hedgerow squares common to this area. VC fighting positions were everywhere, concealing snipers, and the area was heavily booby-trapped. Deadly improvised "VC claymores" completed the defensive scheme of the enemy.

That afternoon, a VC unit was believed to be in the hedgerow squares the company had been searching. A VC claymore was detonated suddenly, wounding several soldiers. The company continue to search, and another explosion occurred as 1LT John Ballard, the company executive officer, followed a wire toward a tunnel entrance. Ballard was killed, and three others were wounded by metal fragments. The wounded included Garrett, platoon leader 1LT Ashcraft, and First Sergeant Alameda. Rifle fire was concentrated on the tunnel entrance, and grenades were thrown into the tunnel. The grenade explosions collapsed the tunnel in on its occupants.

The company, including the wounded leaders, continued to clear the hedgerows, which took about an hour. The wounded were evacuated by air to the 7th Surgical Hospital at Cu Chi, and soon returned to the unit, where they completed their recovery, then returned to duty.

The next day, Major Meloy took the whole battalion in to clean out the area, landing simultaneously at four separate LZs on all sides of the Citadel. It took two days to root out the enemy force, and more than a week to destroy the tunnel network. The Wolfhounds required many tanks of acetylene and several tons of C4 explosives to complete the job.

It was preparation for the Attleboro fighting, which would ensure Garrett’s reputation as one of the great Wolfhound company commanders of the war.

In one sense, Operation Attleboro would be a test of West Point leadership in the battalion. All of the combat commanders of the First Wolfhounds were graduates of the Academy. Major Sandy Meloy was in command of the battalion, Company A was commanded by Captain Dick Cole, Captain Bob Garrett had Company B, and ill-fated Captain Fred Henderson was in command of Company C.

When Garrett was selected to command Company B in April of 1966, Henderson was the company executive officer; shortly to be assigned to the battalion staff until he later got command of Company C. Like most able young infantry officers, Henderson was ambitious and eager for command. Some thought he might have been destined for high places in the Army. Garrett remembered one of the battalion operations officers remarking that Henderson “carried a field marshal’s baton in his pack.” But it was not to be. Henderson would die in combat on 3 November in Attleboro.

Garrett would later say of Henderson,"Fred was a very intelligent, dedicated officer, who could be depended on to support your flank." It is a heartfelt compliment to one company commander from another, and one that honors Henderson in a way that military decorations cannot do. Henderson and his first sergeant, Sam Solomon, who was loved as a soldier's soldier in the battalion died together, in the presence of their battalion commander, Major Sandy Meloy, as described in the first article in Tales of the Wolfhounds.

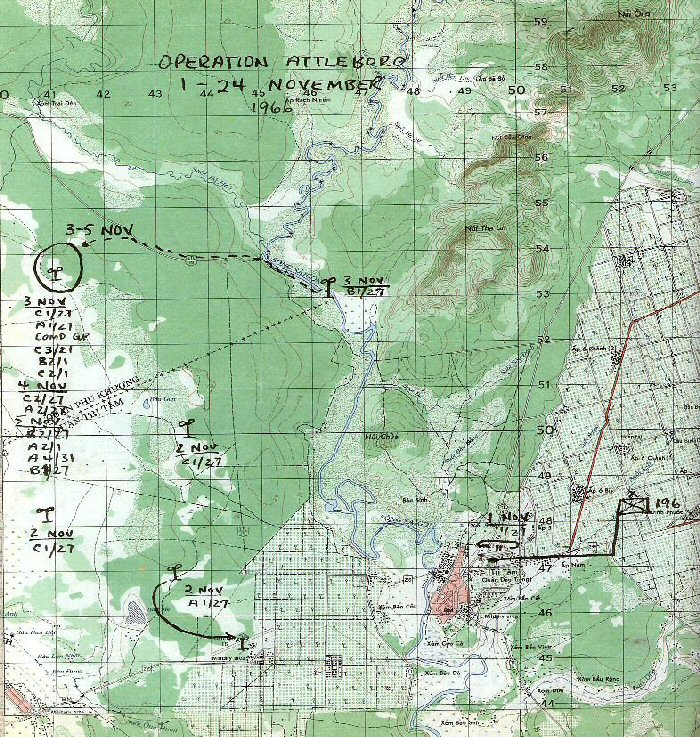

For the Wolfhounds, Operation Attleboro began on 1 November, when the battalion was placed under operational control of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. The 196th was an untried unit that had deployed to Vietnam from Fort Devins, Massachusetts in August. The brigade had initiated Operation Attleboro on 14 September but had no significant enemy contact until 19 October, when a large base area was discovered in Tay Ninh Province. The operation continued until 24 November. It was the largest U.S. Army operation to date and accounted for 1,106 enemy dead. By 5 November, the size of the enemy forces encountered resulted in control of the operation at successively higher levels, until finally the commanding general of II Field Force, a corps-level organization, was in control of it. In the process, the brigade commander, an artillery officer with little or no experience in commanding infantry, had been relieved.

Problems encountered in operational control by the brigade are detailed in a previous Tales of the Wolfhound article, “Sandy Meloy and Operation Attleboro.” At the company level, Garrett had his own problems with the slipshod operational style that seemed to prevail in the brigade.

On the morning of 3 November, Company B was inserted into an LZ covered with tall, dry grass. The LZ was “cold,” which pleased Garrett. Years later he would observe in a letter that any exchange of fire with the enemy would have set the grass afire and forced his company to “run for a swim in the Saigon River.”

Shortly after the unit was on the ground, a huge rice cache was discovered in a metal-roofed shed. The rice was in bags weighing 75 to 100 pounds. Garrett considered reporting the find, then decided against it. “No way were we going to become rice-bag haulers,” he said later. He ordered the rice to be dispersed and exposed to the elements. The shed was destroyed, and the unit moved to its designated blocking position. By mid-afternoon, the company was in position.

Finding no enemy opposition, Garrett wanted to move on to a position that would have placed his company in a position about 1000 to 1500 meters north of the 1-27 Infantry location. His plan to move there had been settled in a radio conversation with his battalion commander. The 196th Brigade would not approve the move, for the reason that it would limit air strikes there if needed that night. Before Company B had completely prepared a defensive position for the night, Garrett got an order from the brigade to move to another position to join two battalions of the brigade. B/1-27 was not to be under operational control of either battalion. “We were guests for the night. They supplied us with water and rations,” said Garrett.

The following day, 4 November, with a less than clear idea of the situation in his battalion, Garrett decided he would move to occupy the trail junction he was prevented from occupying the previous evening. A brief radio conversation with Major Meloy, his battalion commander, confirmed the desirability of his plan. Meloy, who was located in a position about 4 kilometers away, told him to proceed to the junction as soon as possible. It might be possible to trap the enemy between the 1-27units.

When Garrett reached the junction, to coordinate the action of his unit with his battalion located to the south, he realized there was an enemy threat from the north. Garrett ordered an immediate attack in that direction by his third platoon, under 1Lt Rourke. The attack caught the enemy by surprise, and they ran.

Garrett knew the importance of the junction, and he realized he had to be able to counter enemy activity from all directions. After the initial engagement, he kept third platoon on the trail to the north. He ordered the second platoon to cover the road, which ran to the east from the intersection, and the trail to the south. The first platoon would cover the trail to the west and be prepared to reinforce the third platoon in the event of action to the north. Mindful of where the first enemy presence had been, he ordered third platoon to clear the north trail of bodies and set up an ambush 200 meters north of the intersection. Rourke sent Sergeant Bearanaba, his platoon sergeant, with a reinforced squad. They did not have to wait long, and caught a VC force in a classic ambush. Within two minutes, the enemy column had been destroyed, except for one or two at the end of the column, who managed to get away. Later, the enemy probed all three of the platoon positions, but had no stomach for a new attack. A hand-drawn map found on one of the enemy dead indicated the critical nature of the trail/road junction.

Sergeant Bearanaba recovered a VC flag from the body of a dead enemy officer, and presented it to Garrett. He retained it for 26 years, then asked retired Maj. Gen. Sandy Meloy, his former battalion commander, to present it to the officers and men of Company B at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii. The presentation was made, and today the trophy rests among others in the Regimental Room there.

Garrett’s problems with the 196th Brigade’s command and control structure were not over. That afternoon, one of his platoon leaders called him to the junction. On the narrow trail shown as a road on the maps, Garrett greeted two of the battalion commanders of the 196th, 2-1 Inf and 4-31 Inf. They were accompanied by their staffs, along with one company from each battalion, and a jeep bearing enough radios to communicate with any headquarters in II Field Force.

“It looked like something out of a low-budget ‘Sci-Fi’ film,” said Garrett.

The jeep seemed to be a makeshift communications center for both battalions. The brigade had sent the force to reinforce 1-27 Infantry. The battalion commanders seemed willing to turn their companies over to 1-27, but were perplexed at finding only one company from 1-27 at the junction.

Captain Garrett suggested an immediate attack southward to the two lieutenant colonels, to relieve a beleaguered unit, C/2-27 Infantry. That unit had been landed to reinforce 1-27 Infantry. Word had come in that the 2-27 unit was nearly leaderless. The company commander was dead, along with the battalion commander, who had joined the company on the ground.

Garrett recommended that their combined force attack to the south to relieve C/2-27. He reckoned that if the movement got underway by 1700 hours, they could reach the battered company before dark. The commanders seemed reluctant to move, and their staff officers were squabbling about time or lack of time remaining before dark.

Neither battalion commander seemed willing to take charge or to do anything to influence the battle being fought--now not more than 1000 to 1250 meters from them. Outraged by their refusal to act, Garrett told them he was moving his company “to the sound of the guns” unless they or the brigade were prepared to give him a direct order forbidding the attack. Then he appealed to the battalion commanders for assistance. Neither commander wanted to attack with the force at hand, but neither was eager to appear lacking in support for an attack on the enemy. Afterwards, he would privately call them the “command committee.“ Finally, they agreed to the attack. Garrett’s company would lead, and the other two would follow, in a staggered, wedge-like column. The company to Garrett’s left flank and rear would provide rear security.

It was 1730 before they began to move, and the attacking units soon began to receive small arms fire. Company B and the left flank company overcame the enemy fire quickly. But the commander of the right flank company was convinced that his unit was engaged by a superior force. Garrett determined the situation was not serious, but by the time he had calmed the inexperienced commander and convinced him that he could handle the situation, darkness was upon them.

At this time, the brigade radioed a plan for an air strike. The strike would be made at a point between the trail junction and the location of Garrett’s parent battalion, which was located litle more than 1000 to 1200 meters to the south of Garrett's position at that time.

The planned air strike stirred the two lethargic battalion commanders. They were unified in their opposition to it. It also brought an end to the attack. The brigade ordered Garrett’s spur-of-the-moment task force back to the junction.

With the cancellation of the attack, and having not received any night defensive instructions from brigade, Garrett sent his first sergeant to the radio jeep to inquire about plans for a night defensive perimeter. There was no plan. Garrett was obliged to make one himself. He assigned A/4-31 Inf to cover a sector that included the trail running westward from the junction. A/2-1 Inf was assigned a sector that covered the trail to the south and the road to the east. The sector for his own company included the trail to the north, the site of third platoon’s successful ambush. This area was the one with the most enemy activity during the previous day’s fighting.

The units were moving into their positions without incident. Garrett went to the radio jeep/command post to ask for agreement to move south at first light. While he was there, near midnight, the green company commander who had responsibility for the western sector announced that his unit was unable to link up with the left flank element of B/1-27, as ordered. He suggested they let the men rest and take a chance, in hope that the enemy would not discover the gap in the lines.

Garrett blew his top. He told the two lieutenant colonels and anyone else within earshot that the situation was unacceptable. He told them he would drive their radio jeep into the gap before he would permit a break in the lines. His outburst brought the “command committee” around to his point of view. First Sergeant Alameda accompanied the inexperienced commander to a linkup point, and the line was formed.

The next morning, following Garrett’s plan, “Task Force Bravo” would head south to relieve C/2-27 Inf, moving in the same wedge-shaped formation employed the previous day. The “command committee” elected to follow the wedge with the radio jeep.

By noon Garrett had relieved the battered company from the other Wolfhound battalion, but Task Force Bravo was coming apart. A/4-31 left the formation, and Garrett learned later from the company commander that his battalion S-3 had prevented the unit from returning.

Then the “command committee” sent Garrett a radio message indicating that the Sci-Fi radio jeep was stuck between two trees. An exasperated Garrett replied, “Blow the damn thing up and move on.” His command of a three-company task force trailed by two battalion command groups and a radio jeep had come to an end.

A short time later, Garrett entered the 1-27 Infantry position, bringing with him the rescued C/2-27.

Operation Attleboro was to continue until 24 November, through what the 1-27 Wolfhounds called “leech city,” and other adventures, but that is a tale for another time.

The end of the year brought Bob Garrett’s time as a Wolfhound company commander to an end. He left a glowing record as an example to others, and was possibly the best Wolfhound company commander of the war.

Copyright 2007, Howard Landon McAllister