Captain Charles Dewese: The Mayor of FSB Jackson

by Howard Landon McAllister

In 1970, before the combat units of Second Wolfhounds had departed from Cu Chi for the last time, the battalion had occupied FSB Jackson and FSB Chamberlain. At Jackson, the battalion tactical operations center had been a sturdy sandbagged bunker with adequate protection from mortars and other indirect fire weapons. After the battalion had taken part in the Cambodia operation, it was sent to FSB Chamberlain. There the First Wolfhounds had built an operations center with a conventional corrugated metal roof. The roof had a number of green plastic skylights, and during daylight hours, it was possible to operate from the building without using interior lights. Wolfhounds who had experienced mortar and rocket fire at Jackson snorted when they saw the thin skylights, corrugated to smoothly overlap the metal sheets. Looking up, someone ventured an opinion that “we would never have done this at Jackson.” It was a sign of the times. Perhaps it was just another symbol that the war was drawing down, and that we would soon abandon both the war and the country that we had spent so many American lives defending.

Experienced infantrymen know that fortified bunkers are not designed to be fighting positions. Actual fighting positions require an infantryman to use all of his senses to locate and bring fire on an enemy. Ideally, a fighting position in the Vietnam War was a hole in the ground surrounded by filled sandbags, with enough of the bags above the ground to be camouflaged and to offer a bit more protection.

Using a bunker for a fighting position was a last resort, and if an enemy was able to fire an RPG through a firing port, or throw a satchel charge through it, the bunker became more often than not a death chamber for the occupants.

The bunkers were intended to provide protection from sudden attacks with indirect fire weapons and offer some degree of protection from inhospitable elements that made nearly every day in the Vietnam War an adventure in discomfort.

Looking back on that time, it occurs to me that Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer III and Captain Charles E. Dewese would have been two strong forces against such flimsy building practices. Dewese, who had been a tough paratrooper before the war, had served as commander of Company B, and later as the S-3 Air during his year in the Wolfhounds. During his months as a company commander, he was regarded as a mature, responsible leader. Colonel Forest Rittgers, who was one of his battalion commanders in the Wolfhounds, later said the company seemed to be virtually trouble-free and attributed that quality to Dewese’s strong leadership.

Dewese had commanded Company B during a time when the rifle companies of the battalion were engaged in locating and fighting NVA reinforced Vietcong and NVA units . These units conducted frequent cross-border operations from their sanctuary in Cambodia. American policy at the time tolerated the enemy presence in Cambodia, and American forces suffered disadvantages and they fought bloody battles as a result of the situation. In this environment, some company commanders failed to measure up to their responsibilities. Charles Dewese was not one of them.

During the time he spent on the battalion staff, he showed that he possessed another valuable skill. At a fire support base that seemed to change in appearance almost daily, he became a symbol of growth. In a civilian sense, he could have been called the “mayor” of FSB Jackson.

At smaller “hard spots,” as the hastily-built bases were usually called, construction was hurried and only provided a minimum of creature comforts. The ones housing a battalion field headquarters took on a little more grandeur, if the term can be applied to bags of woven polyester filled with sand and earth. The larger the structure, the more reinforcement it required. Wooden railroad ties and sections of pierced steel planking were integrated into the structures to provide lateral stability and overhead support for layer upon layer of filled sandbags.

Provision had to be made for wiring, drainage, limiting access to insects and pests and a dozen other things. The final structure had to be visualized, and that is a skill that requires experience. Failure to plan ahead resulted in leaning vertical lines subject to collapse and other misfortunes. There are no leaning towers in field fortifications, accidental or otherwise.

Photographs from that time show wiry, tanned shirtless men, using posthole diggers, shovel s and other hand tools to raise their projects. Nearby, with a clipboard in hand, Dewese would be standing, checking the lines, asking questions about measurements and other things. Finally, he would say,“That’s enough for now, men. Get out of the sun.”

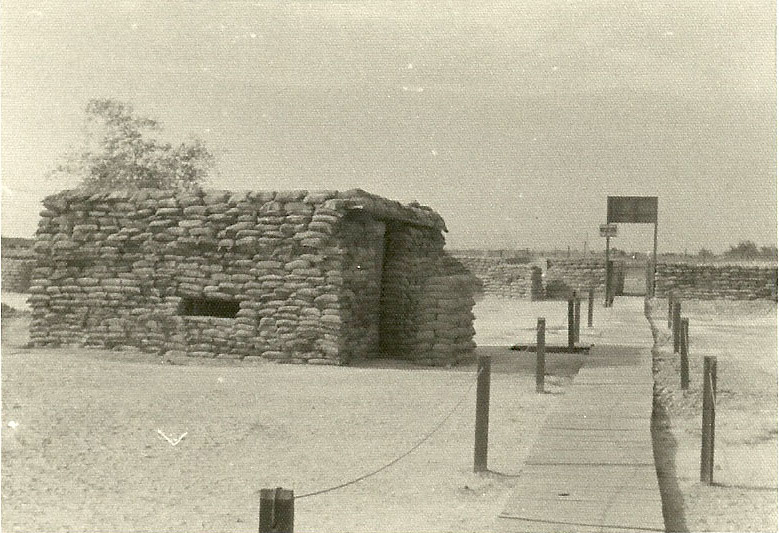

Dewese left the unit to come home before the Cambodia operations. The crowning glory of his bunker-building efforts was a perfectly square structure with taut, precisely filled sandbags laid with an artist’s eye for symmetry. The bunker sat alongside the planked walkway leading from the helipad through an outer line of fighting positions. The walkway terminated at the massive command post bunker. The new bunker had firing ports to provide deadly overlapping fire. No attacker could run across that line and remain alive.

Dewese surveyed the bunker with clear satisfaction, and then moved his gear and possessions into it. It would be his final home in Vietnam. Many former American soldiers have visited Vietnam in recent decades, and some of them have gone to the site. A modern brickworks stands nearby, but there are no visible signs of the domain of the Mayor of Fire Support Base Jackson.

Charles Dewese retired from the Army as a Major at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. His final assignment was with the First Battalion, 502d Infantry (Airborne). At 76, his life today is a retirement dream of many soldiers. He is the patriarch of a large family, and he lives on his 350-acre Tennessee farm tending his cattle and horses. His five children and more than twenty grandchildren live nearby. In his mind’s eye, the Vietnam War is exactly where it should be—long ago and far away.

Copyright 2011 by Howard Landon McAllister