Price Tag in the Renegades: Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye

by Howard Landon McAllister

The price of any war, in blood and treasure, is staggering. And for the survivors, however long they live afterward, fragmentary memories of long dead comrades reawakens a dismal chain of regrets whenever they come to mind.

For me, two particular dates on the calendar provide the sad trigger. On January 6, I always recall that date in1968, when four men in my company, Company A, Second Battalion, 18th Infantry, died in combat in a wooded area near Xom Bung in Binh Duong Province. And every year on April 2, I remember the seven men from the Second Wolfhounds, who, along with three Army Rangers, and an artillery forward observer, died in the Renegade Woods, across the Vam Co Dong River from Tay Ninh, a scrubby knot of mixed canopy jungle that we later Rome plowed to make less attractive to the enemy as a staging and base area. I knew men who died on many other days in the war, but these are the two dates each year when I permit the calendar to automatically assault my sensibilities.

This account is not primarily about battles. It is about price tags—price tags paid in blood. One such price started to be paid early in the morning of 2 April, a short time after two small teams from Company F of the 75th Rangers landed in a clearing in the Renegades. Sergeant First Class Alvin Winslow Floyd, Team Leader of Team 38, from Augusta, GA and Sergeant Michael Francis Thomas of Louisville, KY, a member of the same team, lay dead in a large bomb crater near one end of the clearing. And before the fighting had concluded several days later, nine other Americans had lost their lives in that grim forest. When it was over, another Ranger, Specialist Four Donald Tinney, of New York City, would be dead, although Tinney would hang on to his life in a hospital for another twelve days.

Company C, 2-27th Infantry lost five. Specialist Four Mickey Griffith, from San Gabriel, CA, and Specialist Four John Edward Rarrick, of Beaver Dams, NY were in Charlie Company. Private First Class Severiano Rios, who joined the Army in Oak Creek, WI, was another, along with Staff Sergeant Melvyn Hamana Kalili, Platoon Sergeant of the first platoon. He was from Hauula, HI, and I remembered his easy smile and the small can of Macadamia nuts we had shared on an ambush patrol shortly after he came to the battalion, barely a month before. From the right flank, Second Lieutenant Ronald V. Kolb, of Washington, DC, the platoon leader of the third platoon, started to maneuver his platoon around the heavily engaged first platoon, where the platoon leader, Ronnie Clark had been gutshot. Clark would survive, but his Platoon Sergeant, Kalili, was already dead, after going to the assistance of a downed point man. And Kolb didn’t live long enough to complete the maneuver. As he brought his men up on the left flank of the first platoon, a burst of fire took him out. All of the Charlie Company men died that first day of the battle.

Company C had been the first unit to respond to the attack on the Rangers. Then two additional Wolfhound units went into the fray on April 2, Company B and then Company A. By the next day, two mechanized infantry companies from Second Battalion, 22nd Infantry (Triple Deuce) had come under operational control of the Wolfhounds.

Two men from Company B lost their lives on April 2. They were Specialist Four John J. Lyons, who was a radio telephone operator from Yonkers, NY, and Sergeant William Thomas Smith of Marshfield, WI. I helped two of Lyons’s anguished comrades carry his body to the helicopter LZ. He was cool and pale in death. He was twenty-one, but he looked younger, killed quickly by the same unseen sniper who had taken the life of the company's artillery forward observer, in one flashing scene of violence a short time before. The artillery officer was Second Lieutenant Orville Eugene Kitchen, Jr., of Battery B, Second Battalion, 77th Artillery. Kitchen's home was in Dayton, OH.

Company A had one man killed on April 3, twenty-year old Dwight Herbert Ball, of Sardis, OH, whose family members would leave loving, plaintive messages along with his photo more than thirty years later on the Virtual Wall.

The aircrews and the men of the Triple Deuce were luckier in the battle, and none was claimed by the Grim Reaper.

It had taken the efforts of hundreds of infantrymen and airmen to root out the enemy. The price paid by the North Vietnamese Army was heavy. We counted 101 battered bodies in the battle area, and two enemy soldiers were alive in American hands. One was classified as a prisoner of war, and the other a Hoi Chanh, or rallier to the cause of the South Vietnamese. Cynically, we sometimes said Hoi Chanhs were merely NVA who had decided to go on R&R from the war for a while, but this one was duly handed over to the South Vietnamese, to let them sort it out.

When it was all over, and we dragged our weary bodies off the helicopters at FSB Jackson, a knot of men were waiting at the helipad. A black soldier I recognized as a good friend of Rios ran up to me. I read the question in his eyes, but I knew the worst and could only shake my head.

As I walked through a sandbag portal and headed for the CP, a dry-mouthed rage built within me. I had seen the ragged enemy dead, and I knew that we had fought as well as we could, and we had used artillery and airpower prodigiously, but at that moment, nothing seemed like enough. I knew it was not rational, but if it could have kept alive some of our men who died, at that moment I would have killed every Vietnamese on the planet and bankrupted the United States Treasury. I knew more than I wanted to about price tags.

All of our dead got Purple Heart Medals, along with the others who were wounded. I recommended other decorations for most of the men, living or dead. The dead soldiers were promoted one grade after death. It meant little more than recognition and a few more dollars for a grieving relative at home, but it was also symbolic. Among the award recommendations was one for the Distinguished Service Cross for John Rarrick, the lean, muscular sergeant from Beaver Dams, New York. It was one of the recommendations that made it through, and the medal was awarded. I thought about putting something from his citation here, but I decided not to do it. I have seen award recommendations written with sweaty or bloody hands on c-ration boxes and scraps of paper. They were messages from the heart written as tributes to dead comrades. However, men who work in offices with fans or air conditioning write the actual citations. The finished product often bears little resemblance to the real event. That does not really matter. What does matter is that a grateful nation honored a brave son with a symbol of that gratitude.

Rest in peace, Renegade Woods warriors. The price was still too damn high.

©2006, Howard Landon McAllister

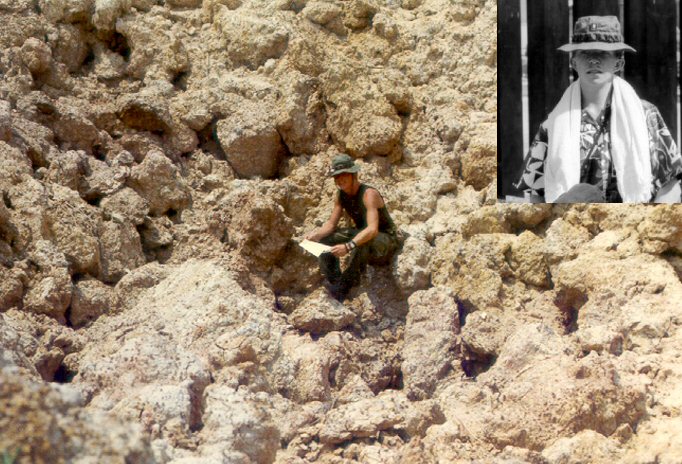

Specialist Four John Edward Rarrick, Company C, 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry (Wolfhounds) catches some sun and reads his mail in a bomb crater (inset: Rarrick at a stand down at Cu Chi). Rarrick was posthumously promoted to Sergeant and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism.

Private First Class Dwight Herbert Ball, Company A, 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry (Wolfhounds). The photo was taken following his graduation from basic training. Ball was posthumously promoted to Corporal. (Photo courtesy of Helen Wyckoff, Ball's sister.)

Author's Note

Those who are interested in reading a detailed official historical account of the Renegade Woods fighting can find it on the Internet using the link below. This historical report was prepared by the Army's 18th History Detachment in 1970, and it is among the most complete reports of its kind, with statistics and photographs. If lacking anything, it was the details remembered by individuals who took part in the action. The author, who commanded the infantry units on the ground, continues to collect such information, and perhaps one day these personal accounts will appear here in Tales of the Wolfhounds.

Historical Resources Branch U.S. Army Center of Military History – Renegade Woods