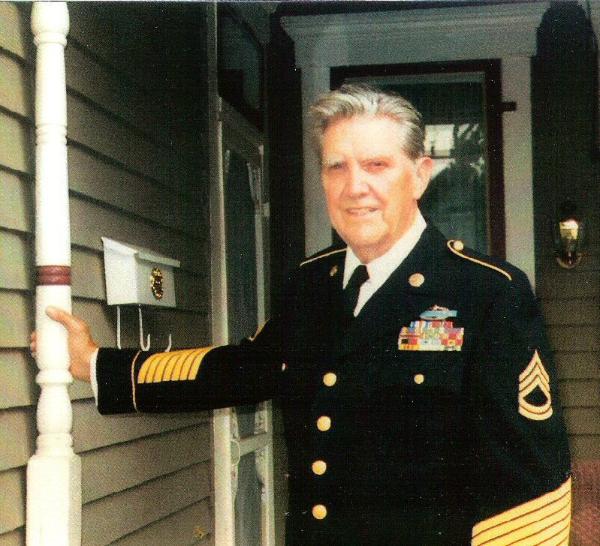

Rock Green – Always a Wolfhound

by Howard Landon McAllister

Wolfhound warriors come in many shapes and sizes—and ages. Far from being cast in a “mold” of any kind, their backgrounds and experiences vary greatly, even among those who were career soldiers. No one could represent this statement better than Charles Welby “Sergeant Rock” Green, who was able to get three assignments in two wars in Wolfhound units. With typical Wolfhound pride, Green says, “Might as well shoot for the best.”

His service goes back to World War II. Born in 1926 in Providence, Kentucky, he was drafted into the Army in October 1944, a few months after his eighteenth birthday. He was sent to Europe early in 1945. One of many infantry replacements assigned to a field artillery battalion, Green and his companions were assigned to guard duty to free the trained artillerymen for around-the-clock firing missions along the Rhine River.

The war was soon over, with the German surrender in early May. After the war, in 1946, Green was mustered out of a rapidly contracting Army. By 1949, dissatisfied with his prospects in civilian life, he returned to the service. This time the Army assigned him to an artillery unit in Fort Bliss, Texas, as a cook.

By the time the war began in Korea, he had joined the 27th Infantry Regiment, and was soon the mess sergeant of Company D, of the First Battalion. His 13-month assignment was during the height of the campaign to retake most of the South Korean territory from the invading North Koreans. Anyone who thinks of an infantry company mess section as not in combat should get an opinion from some of the Korean War Wolfhounds who lugged Mermite containers of hot food up to platoons on the line while under observed fire from Chinese and North Korean riflemen. Green saw his share of these perils during his year in the Wolfhounds.

A dozen years after Korea, Rock Green completed his lengthy occupational transition to Wolfhound combat leader in Vietnam, and how he did it is a study in perseverance. The years between the wars were a story of frustration for Green and other soldiers.

It was the age of Air Force ascendancy and big bombers, of Brinksmanship, Mutual Assured Destruction, cold wars, and tight budgets. The Army drew short shrift. There was little money for infantry weapons systems, and what there was went for pseudo-scientific junk such as the French-designed Entac—an improbable wire- guided missile designed as an anti-tank weapon. More often than not it belly-flopped its way downrange to explode harmlessly against a stump or a clump of vegetation. Even more ridiculous was the Davy Crockett, a so-called infantry nuclear weapon, which resembled a small blimp mounted on a stovepipe, fired from an ungainly ground mount or a jeep. Colonel Robert B. Nett, an infantry hero of World War II, suspiciously eyed a Davy Crockett at a demonstration at Fort Benning in 1962 and observed, “It looks like it could be as dangerous to us as to an enemy. Might as well be talking about a nuclear hand grenade,” Nett grinned sardonically past the cigar clenched in his teeth.

The Army had found a little money to upgrade the venerable M1 rifle of World War II and the Korean War with the M14 and had already noticed the little black rifle, which later became the M16. It was a better rifle than the ammunition at first supplied for it, but there was room for improvement in the rifle itself. The noncommissioned officers didn’t trust it, for one thing. “Looks like a damn BB gun,” was the usual complaint. Other than the rifle, the infantryman’s personal equipment was little changed from that used in World War II.

Money for training was curtailed as well. Rock Green’s Army of that time was too quick to regard on-the-job- training as a substitute for the real thing. Too often military occupational specialties were assigned on the whim of a harried personnel officer faced with many square pegs to fit in round holes.

For many peacetime soldiers, it was a time of broken promises and false hopes, especially among the career noncommissioned officers, when promotion opportunities dried up. Green spent years as an investigator in the Criminal Investigation Division. That career field proved to be a promotion dead end for him. In desperation, he finally accepted an assignment as a chaplain’s assistant on the promise of a promotion to Specialist Seven, the pay grade equivalent of a Sergeant First Class. But in his heart, Rock Green was an infantryman, and when the Army sent him to Vietnam as a chaplain administrator in a logistical command, in the fall of 1966, he knew what to do. When he arrived at Long Binh, he requested assignment to the Wolfhounds, knowing the 25th Division was a short distance up the road at Cu Chi. Combat units are always short of men. The request was approved, and he hitched a ride on the daily convoy to Cu Chi. He had come full circle. He had come home.

He was assigned to the Second Wolfhounds, at first as a temporary replacement for the first sergeant of Company C, who had been killed shortly before Green's arrival. After two months in the job, a qualified E-8 first sergeant arrived, and Rock was assigned as the “field” first sergeant of Company C. The position was one that most rifle company commanders found indispensable in Vietnam, although the job is not officially recognized in Army tables of organization. By the middle years of the Vietnam War, the company first sergeant of most infantry units was fully occupied with assisting the executive officer and others in management. Company administration had become very complex.

The “field first” was usually the chief troubleshooter for the company commander, responsible for myriad details that came up every day and in every operation in the field—organization for receiving supplies, setting up pickup zones for airmobile operations, finding replacements for lost or damaged equipment—you name it. He may not have been involved in direct troop leading within the platoons---until one of the platoon sergeants got killed or wounded. When that happened, guess who usually got to take over for the lost leader, at least temporarily. It was the field first sergeant.

Except for his two months plus as acting first sergeant, Rock Green spent his entire year in the field with the company through the wet season and dry, with numberless eagle flights into numberless LZs, some of them hot ones. Wolfhounds were always grateful when they were not hot.

One of the little touches Green cultivated as field first sergeant was to greet every new man who joined the unit in the field. If the soldier was a little jittery, he usually found time for an encouraging talk, ending with "You'll be OK, kid.” More than 40 years old at the time, he must have seemed ancient to them.

Charlie Company was a fighting unit, and the unit had its share of casualties, including company commander Riley Pitts, who earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courageous leadership—at the price of his life. But Rock Green was lucky—no enemy bullet found him in that year. The time flew by, and at the end, Green went home. On the last day of 1967, his name was put on the retired list.

The retirement didn’t take. Green accepted a job as an instructor in a high school ROTC unit in Washington, DC. The war in Vietnam went on. Soon he learned that the Army was accepting requests from men on the retired list to return them to active duty. By early 1969, he had lined up a set of orders recalling him to active duty and had orders directly assigning him to the 27th Infantry in Vietnam.

When he got to Long Binh, the fireworks started. With typical contempt for assignment arrangements made without their participation, a snotty USARV assignment officer decided Green would go to another infantry unit. Rock knew how to deal with that one. “You will send me to the Wolfhounds or I’m going back home on the next plane.” The assignments officer got the message. After a brief telephone conversation, the orders were changed, and he was on his way to Cu Chi.

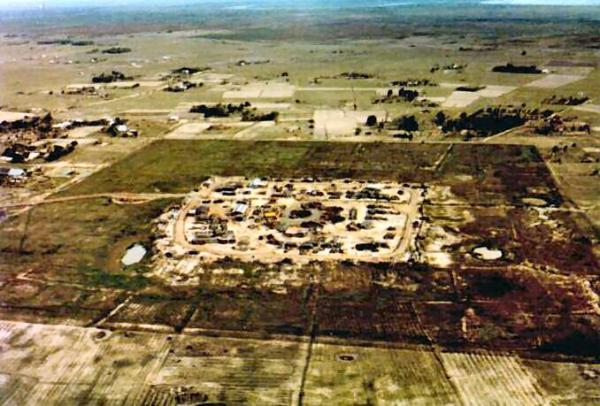

Next stop was Fire Base Mahone II, a scruffy fire support base a few kilometers from Dau Tieng, where Green reported in to the First Wolfhounds, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James T. Bradley, who was known to his men as the “Bear,” for his blocky appearance. He had been a collegiate tackle with extraordinary strength and stamina. In earlier Army assignments he had delighted his friends by repeating conversations between himself and his friend, the great NFL tackle of the Baltimore Colts, Gene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb. Bradley reveled in Lipscomb’s descriptions of how he tackled runners by picking up groups of players, shuffling though them until he found the ball carrier. Bradley’s style, enthusiasm, and manner of dealing with his men inspired fierce loyalty, and he and Green hit it off from the beginning.

Their relationship was to become one of the exceptions to normal procedure. Green had impressed Bradley from the start. After seeing him take charge of a marginal platoon, quickly turning it into a good one, the battalion commander was in no hurry to change the mix. Rock Green remained in command, and the platoon went without a commissioned officer as platoon leader from the time Green arrived until July of 1969. Lieutenants who reported in to the battalion went elsewhere—not to the 1st platoon of Company D.

When Green took over the platoon, he knew he had his hands full when he immediately took his seventeen sullen soldiers on a short patrol outside the wire at Mahone. He wanted to gauge their state of training and capabilities, and what he found was not encouraging.

After they had finished the patrol and were back inside the fire base, Green assembled them beside one of their bunkers, and read them the riot act, telling them among other things that they were not in Vietnam to take strolls in the sun, and that he had not returned to Vietnam from retirement to view their dead asses being sent home in body bags. Green later found out that the nickname he gained, “Sergeant Rock,” originated in the platoon that day. Originally meant as derogatory, the name finally became the term of address used by all of the men for an admired leader.

The harsh words of the first meeting were followed by an immediate and intense training effort. Training, fired by the magnetism of good leadership, was all that the platoon needed. They worked hard, began to develop a sense of pride, and their performance steadily improved. The platoon filled out to about 30 men, closer to its normal complement. The increase in performance and improved alertness reduced casualties. During the next couple of months, only one man was wounded in action, and it was a minor wound. They began to talk about being the best platoon in the company.

The improvement in performance coincided with a change in operations in May of 1969. The battalion began to concentrate on platoon-sized operations, mostly search and destroy operations and night ambush patrols.

On one ambush, the platoon captured a Vietcong soldier. The next morning, when the battalion was notified, Green was told a helicopter would be dispatched to the platoon position immediately to pick up the prisoner.

Green thought about the scarcity of fresh water, and replied, “We’ll trade you the prisoner for 20 gallons of fresh water.” When the helicopter arrived, four white plastic containers of fresh water were offloaded, and the prisoner was led aboard.

In July, the battalion moved from FSB Mahone II to FSB Chamberlain, a square-shaped fire base southwest of Cu Chi. The Wolfhound units concentrated on joint operations with South Vietnamese units. Green’s platoon was given the mission of providing security in a village. An ARVN company of about 110 men shared in the security arrangement.

Green’s platoon occupied positions covering half the perimeter, with the platoon command post located in a vacant house close to the bunkers of his squads. Green thought the setup was vulnerable to enemy attack. “It was like we were bait in a trap, but there was no trap to spring,” he said.

His instincts were right. The attack came just after midnight. The day before, July 21, had been his 43d birthday. He had finished his turn on guard duty in the CP, facing out toward a rice paddy that served the platoon as a helicopter pad. Shortly afterward, he fell asleep on a large wooden table, with his boots off and his M-16 cradled in his arms. Suddenly, a powerful explosion shredded the roof of the house. He rolled off the table, ran outside the house in stocking feet, and began firing at obvious enemy movement in the rice paddy. When the magazine in his rifle ran low on ammunition, he went back inside the house to retrieve a claymore bag with twenty loaded magazines in it. Explosions continued, and by this time the entire back of the house had been blown away. As Green crouched in the space where a doorway had been, another explosion, accompanied by a blinding flash of light, lifted him. He came down facing in the opposite direction. He became aware of blood oozing from many holes in his legs. Later he could not recall losing consciousness, but he thinks he must have. Doc Taggart, the platoon medic used the bandage in his first aid pouch to make a tourniquet for his right leg.

It took several hours to get a Dust Off helicopter. Green remembers that Specialist Four Robert Bruening, an RTO, who was also seriously wounded, was lifted out on the same evacuation helicopter. The evacuation was not without a few problems. The ARVN soldiers who moved him to the helipad were unable to lift his six-foot plus frame, so they dragged him to the pad, through some cactus and other vegetation. When he was placed on the stretcher in the helicopter, his stomach chose that moment to reject the meal he had eaten at 1700 the day before, and it spilled out on the floor of the vibrating helicopter.

“Good thing they picked the bottom stretcher for me,“ Rock recalled later, with a rueful grin.

Green’s war was over. After triage at the 12th Evacuation Hospital at Cu Chi, he was moved to the 4th Evacuation Hospital in Saigon for surgery, then on to Okinawa for skin graft surgery. Finally, he was sent to convalesce at the Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia. When he was released from the hospital, he convinced an Army medical board that he could handle limited duty in an intelligence unit buried somewhere in the bowels of the Pentagon. He served there until May of 1972, when he went back on the retired list. Today he lives in Indianapolis with Nora, his wife (Mama Rock to most old Wolfhounds).

Next time someone reminds you about NCOs being the “Backbone of the Army,” you can think of Charles Welby “Rock” Green. You will never find a better example.

Copyright 2006, Howard Landon McAllister