Ruben Ford – Wolfhound and Mentor

by Howard Landon McAllister

Years ago, when I began gathering information from former Wolfhounds around the world, I wanted to tell their Vietnam stories as clearly as possible. The official records were mostly written in the sing-song language of military bureaucrats. They were of little value beyond establishing a chronology of events. The most valuable records were the Lessons Learned —brief, relatively clear accounts of fighting designed to help future combatants avoid situations that would get them killed or wounded.

The painful truth is that an infantryman’s war is a grim, hazardous occupation, then and now. Much of it depends on the luck of the draw. The horrible, glaring error of the Vietnam War is evident in the huge black monolith of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington.

We can hope that it is ingrained in our national psyche in such a way that it can never happen again in the way that it did. But I am a lifelong skeptic.

The draft, the so-called selective service system, made the carnage in Vietnam possible. Like other roads to hell, it was paved with good intentions. And like many other intentions expressed by election-driven American politicians, they come up short, more often than not.

During World War II, when resources had to be balanced to cover a global war, the draft made sense. But in Vietnam, when the open-end method of supplying replacements to military activities around the world was telescoped downward, it was for a limited war. It was a war that in the end our politicians would not have the guts to win.

Gradual escalation is not unusual in war, but since the Vietnam War, any general or politician who would suggest an individual replacement system could rightly expect to be cashiered or turned out of office. Not that the corrective swing is much better. An all-volunteer army creates a class system among our citizenry that enables military adventurism around the world. Even with its inequities, a military draft served us far better than an all volunteer force. The very politicians who are the least competent to make judgments involving the use of military force abroad are the first to spout cliches about the principle of civilian control of our armed forces. Presuming that any American politician who has not had military service is competent to interpret the advice of those who have is a dangerous stretch. We would be better off with a universal service requirement that required service from every able-bodied American, as a prerequisite for seeking political office—from any position ranging from a local school board or municipal office to President of the United States.

When I set out to tell the story of Wolfhounds in the Vietnam War, I enlisted the help of everyone I could find who had knowledge on the subject. One of my early mentors was Ruben Ford, a soldier of many talents, who began his military career following a brief but exciting stint as a runner of moonshine whiskey—straight out of Thunder Road. A level-headed schoolteacher relative set him straight.

She had learned about human frailty from observing her students, and along with an obliging local judge was the main factor in his transformation. Ford took to the competitiveness of army life instantly. After the required training, he was assigned to the First Wolfhounds at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii.

We exchanged dozens of letters, examining in detail his observations about the men and circumstances of the fighting after the Wolfhounds were in Vietnam. In hindsight, what finally surfaced from our letters was an opinion that mid-1960s training of U.S. infantry—based on the concept of fighting the Soviet Union in Europe, was nearly worthless in a war against the enemy we met in Vietnam. To the Army’s credit, the training base in the United States had rapidly adapted to the reality of the war, but the reality of the individual replacement system robbed the training of its value.

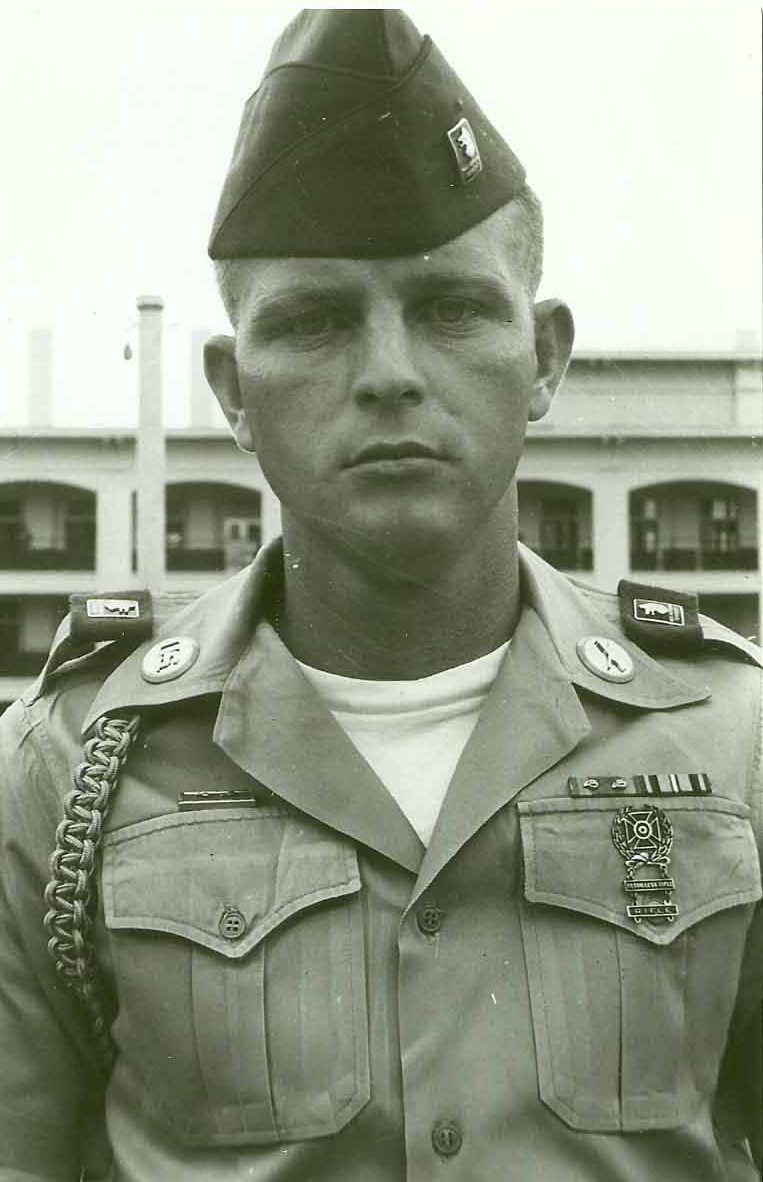

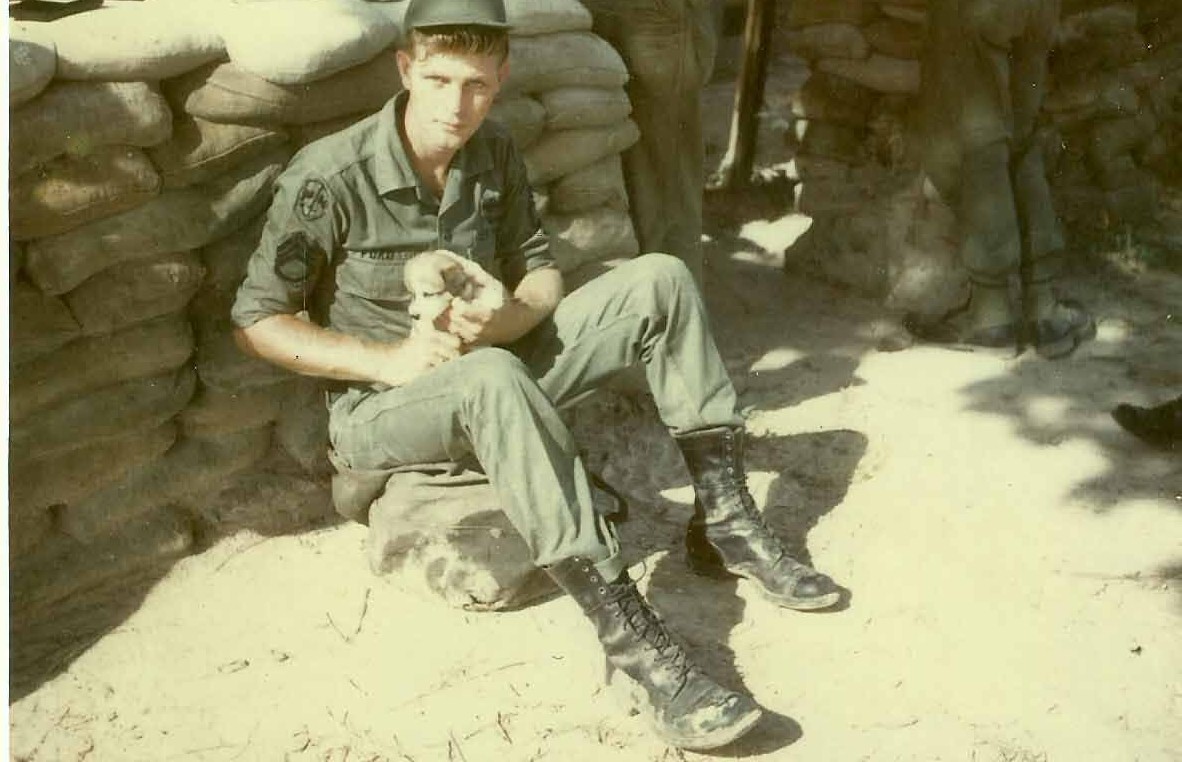

Ruben Ford was a forward observer for the 4.2-inch mortars used in those days, and his days were spent in supporting one or another of the battalion’s companies. His job was as risky as any in the battalion, but he was a high-roller, and he seemed to enjoy the risks. They did not keep him from relaxing when he could. Off-duty photos of the period show a lean young soldier with a puppy on his knee.

The realities of combat also did not keep Ford from continuing to run the risks. He moved on from an infantryman’s war in the Wolfhounds to other fields. Among them was service as a helicopter crew member.

When it was all over, he had gone home with a Distinguished Service Cross, and a healthy start on an Army career that ended when he retired as a Command Sergeant Major many years later.

In our conversations, Ruben helped me expand the envelope of my experience beyond the time I spent in the war, and he helped me understand the experience in a new light. In frequent email discussions, we worked our way through a labyrinth of decades-old reports, many formerly classified. He remembered actual conversations in the units related to the incidents in the reports. We speculated on how the real events may have differed from the reported events. It was the process of seeing history in the raw—warts and all. Our detailed email discussions enabled me to achieve a new balance and a new perspective on the war.

It was most noticeable in my attitudes involving the experiences of others. The American Indian maxim about walking a mile in another person’s moccasins took on new meaning for me. And it extended to everyone who shared their views of their war experience with me.

The exchanges between Ruben and me began after we had both retired, and extended to many things other than the Wolfhounds—letters, photographs, books, and the best smoked salmon I had ever eaten —caught by Ruben and prepared by his skilled hands and those of his wife.

Finally, he apparently tired of my interminable letters. I have always likened researching and writing history to making sausage, and I do not expect others to suffer it long. Anyway, we lost touch. His son was an infantry officer who was serving in combat in the Middle East when I last heard from Ruben. The Vietnam War had come full circle.

I did not serve a single day with Ruben Ford in combat, but he helped me put his experience in the war into balance with my own time there. And he helped make it possible for me to relate more meaningfully to the new things I was learning from others about the Vietnam experience. He had the gift of communicating the things that all infantrymen shared in whole or in part. In that way, he is emblematic of all of us who served in the Vietnam War—the living and the dead—the infantrymen.

Copyright 2010 by Howard Landon McAllister