Wolfhound Commanders I: Sandy Meloy and Operation Attleboro

The Wolfhounds of the U.S. 27th Infantry have a reputation for toughness and resourcefulness as warriors that goes back to the days of the regiment's service in Siberia during World War I. In its turn, the Vietnam War produced heroic infantrymen who added luster to the regiment's history. One of the names enriching the unit's legends is that of Major Sandy Meloy, who commanded the First Battalion of the Wolfhounds during Operation Attleboro in November 1966. How Meloy came to command his unit is a story best told in his own words, and it is related in another article following this one.

In Attleboro, Meloy took his battalion into combat on 3 November 1966 under operational control of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. Two days before, the First Wolfhounds had been attached to the brigade in response to intelligence reporting the presence of the 9th Viet Cong Division, a Main Force unit. In what was to become a command and control nightmare, over the next few days, Meloy's battalion was reinforced piecemeal, until he was finally in command of 11 rifle companies, eight of them from battalions other than his own.

The German philosopher Carl Jung used the term "synchronicity" to describe causality. If the term has merit, it would seem that it could be applied here, when an unfavorable military situation existed for American infantry units in a battle and when the right leader turned up, almost as if it was his destiny. If an overworked term ever made sense, this is probably the place. Major Guy S. Meloy III was the right man for the right place and time. The fact that he was there proved to be fortuitous for the units fighting in the battle under his command. But no commander would have deliberately chosen to place himself in such surroundings. The operations plan was flawed from the beginning, and modifications to it were not improvements. The plan was one Meloy had argued against, only to be overruled by a senior commander. It was a case of growl you may, but go you must. The terrain was awful--mostly dense, triple-canopy jungle, communications were inadequate, and information on enemy dispositions was largely nonexistent. The only things he had going for him were his training--and guts. He was a senior major, a seasoned troop leader, with service in infantry, mechanized, and airborne divisions. Previously in his career, he had commanded four platoons and three rifle companies, and he had been in command of his battalion long enough to be certain of the capabilities of his subordinate units and leaders. A graduate of the US Army Command and General Staff College, he had also served as an instructor there, teaching Joint Airborne Operations. He had been selected to command the First Wolfhounds following six months service as the US advisor to the elite Task Force One of the Vietnamese Airborne Division. This array of solid military credentials proved to be a priceless asset in Operation Attleboro. Allied with his natural coolness under fire, which is not learned in any school, his leadership turned what might have become a military disaster into a significant victory. A bad battle plan had found a good leader. Soon after the fighting was over, the brigade mission was in the hands of II Field Force Vietnam, the corps-level equivalent of the command structure in the Vietnam War, and the commander of the 196th Light infantry was relieved.

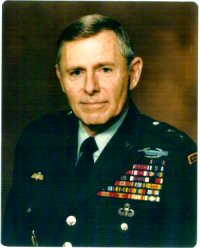

Major Meloy was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism and his second Purple Heart for wounds suffered in the Attleboro fighting. Later, he served a second tour in Vietnam in 1970-71, this time as commander of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division. During this second tour, his battalion operated mostly in War Zone D, not far from the scene of the fighting at Dau Tieng, Prior to his retirement in 1982, he served as commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division from 1978 to 1981. He presently lives in central Texas, with his wife Harriet.

Except for accounts published in Vietnam Magazine, mostly in 1997, the published material on the battle lends little understanding of what happened there; in Meloy's own words, some of it is “borderline fiction.” One of the Vietnam articles was based on a 1992 lecture presented to Wolfhound officers at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii by Meloy, who was by then a retired major general, and an October 1996 interview conducted by retired Army Colonel John F. Votaw at the 1st Infantry Division Museum.

In 1969, the late Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall, USAR published a book purported to be an accurate account of the battle. The book was titled Ambush, with a torturous subtitle: The Battle of Dau Tieng, also called The Battle of Dong Minh Chau, War Zone C, Operation Attleboro, and other Deadfalls in South Vietnam. In his byline, Marshall styled himself an “Operations Analyst U.S. Army in Vietnam.” Even if the reader is charitable, today the book must rank as one of the clumsiest descriptions of any battle in the history of the American fighting man. As a military historian, and one who received an enormous amount of support from the Army and its leadership throughout his career as a writer, Marshall is not wearing well in these first years of the 21st Century. Much recent criticism has been leveled at his writing and his research methods. His detractors have been reputable military historians and other individuals who worked with him in various capacities while he was conducting research within the Army. Some of the criticism is examined in detail in an article in the Autumn 2003 issue of Parameters, written by John Whiteclay Chambers II, former history professor and Chair of the History Department at Rutgers University.

Shortly after the publication of Ambush, in May 1969, the Office of the Chief of Military History in Washington asked then Lieutenant Colonel Meloy to review and comment on the book for accuracy. Meloy concluded that at least half of the book was fictional with little relation to the actual battle, and he scored the author for flippancy and sarcasm. Meloy's review of the book contained a number of general comments and more than fifty specific citations of errors in fact, omission, or conjecture on the part of Marshall. Ironically, none of it gained public attention, and the book went unchallenged. In the bitter aftermath of the Vietnam War, it might have been just one more public relations battle the Army chose to avoid. Marshall died in 1977, and his flawed book has been largely forgotten.

What follows here is a description of the battle chiefly drawn from the videotaped 1992 Schofield Barracks lecture by General Meloy, the October 1996 interview by Colonel Votaw, and the October 1997 Vietnam Magazine article. The latter was a transcription of General Meloy's remarks into a question and answer format by the late Colonel Harry G. Summers, Jr., editor of Vietnam.

An account of the battle written by retired Army Colonel Charles K. Nulsen, Jr., a 1949 USMA graduate, was also consulted in preparation of this article. Titled “Operation Attleboro: The 196th Light Infantry Brigade's Baptism of Fire,” Nulsen's writing is a lucid description of the command and control problems encountered in the battle. Nulsen commanded the 3d Battalion, 21st Infantry, one of the battalions in the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. In his first Vietnam tour in 1962-63, he had been the senior adviser in the Phuoc Binh Thanh Special Zone where he worked with the ARVN Rangers, who were engaged in search-and-destroy missions into Viet Cong areas of War Zone D and elsewhere.

Operation Attleboro, named for the Massachusetts town, began on 14 September 1966. Initiated by the 196th Light Infantry Brigade, a unit that had arrived in Vietnam a month before, the first of two phases in operations included a series of search-and-destroy operations ranging eastward about 20 kilometers from the brigade base camp at Tay Ninh to the edge of the Michelin rubber plantation and the town of Dau Tieng at the southwestern corner of the plantation.

Under command of Brig. Gen. Edward H. DeSaussure, an artillery officer and a former assistant division commander of the 25th Infantry Division, the three infantry battalions assigned to the brigade included the 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry; the 3d Battalion, 21st Infantry; and the 4th Battalion, 31st Infantry. An artillery battalion, the 3d Battalion, 82nd Artillery, equipped with 105mm guns, was also assigned to the brigade.

During the initial phase of operations, the U.S. units made a number of light contacts with local Viet Cong units and discovered a number of enemy rice, weapons and equipment caches. Near the end of October, intelligence indicated that the 9th Viet Cong Division, which had been badly mauled in an operation called El Paso in June and July, had been re-equipped and retrained in enemy training areas along the Cambodian border and had started deploying in War Zone C, the name given an area north of Tay Ninh. The boundaries of the zone followed the Cambodian frontier along its western and northern boundaries, and Highway 13 formed the eastern boundary, running north from Ben Cat to the border.

By 28 October, the regiments of the 9th Viet Cong Division—the 271st, 272nd, 273d, and the 101st North Vietnamese Regiment--were reported to be heading for the Dau Tieng area. On that same date, units of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division made contact with a battalion of the 273d to the east of the Attleboro area. This set the stage for Phase II of the operation.

Phase II began on 1 November. The discovery of large quantities of rice and other foodstuff and the requirement to secure the captured supplies had led the 25th Division commander to placing the First Wolfhounds under operational control of the 196th. Initially, the Wolfhounds were given the mission of securing the airstrip at Dau Tieng and conducting “eagle flights”--the term used to describe special helicopter-borne infantry assaults--in the areas where the enemy supply caches had been found.

On 1 November, two of the brigade's battalions--the 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry and the 4th battalion, 31st Infantry--were occupied in securing food caches and patrolling about three kilometers to the northwest of Dau Tieng town. On 2 November, the two battalions continued this mission, while the Wolfhounds conducted eagle flights three kilometers north of the two patrolling battalions.

Later on 2 November, a plan for the following day was set out by the brigade staff. The plan called for the establishment of a blocking position by one of the Wolfhound companies on a former highway, LTL19, some 10 kilometers from Dau Tieng. The highway had become little more than an overgrown trail near the point where a stream called Suoi Ba Hao flows into the Saigon River. In Ambush, S. L. A. Marshall called the trail “Ghost Town Trail,” a name he apparently concocted, since none of the participants in the battle knew of the term during the fighting.

Another of Meloy's companies was to be inserted more than five kilometers from the one in the blocking position, splitting his battalion in the face of a larger enemy force—a gross violation of Army tactical doctrine. To further complicate an already unworkable command and control scheme, the brigade operations plan called for two of the brigade's assigned infantry battalions, 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry and 4th Battalion, 31st Infantry, to conduct attacks squarely between Meloy's widely separated companies.

Meloy made strenuous objections to the plan. He was later to say, ”The plan was ludicrous. Command and control of the separate attacks was impossible. There was no linkup plan whatsoever. There was no appreciation of either the terrain or the enemy. I had a rather heated discussion with DeSaussure before the operation began. But since I was a major at that time, and he was a brigadier general, obviously I lost.”

The operation got underway at 0900 hours on 3 November, when 2-1 Infantry and 4-31 Infantry attacked along four axes designated by colors--Red, Blue, White, and Purple.

About 0920, Company B of the First Wolfhounds, commanded by Captain Robert P. Garrett, was inserted at a “cold” Landing Zone west of the Saigon River near its designated blocking position. Shortly afterward, Company C landed, also unopposed, in an LZ at XT 410535, approximately four kilometers from Company B. The area at the LZ was covered by elephant grass that was ten feet tall in places. The commander of Company C, Captain Frederick H. Henderson, started his company moving to the northeast and a planned linkup with Company B. After the company had moved from the elephant grass into the jungle, it soon made contact with the Reconnaissance Company of the 9th VC Division, which was guarding a large base camp concealed in the jungle. A savage firefight erupted, in which six men from the company were killed and another six were wounded, including the company commander and first sergeant. The intensity of enemy fire drove off medical evacuation helicopters.

Seeing that the situation was rapidly deteriorating, Meloy knew he had to get on the ground. Trying to command infantry from the air is like trying to push a wet noodle. In what he would later call “dumb decision number 1,” he had the pilot of his command-and-control helicopter fly low over the LZ, and the entire battalion command group jumped out--battalion commander, command sergeant major, artillery fire support coordinator, and three radio operators. The sergeant major was hit, and the helicopter took several rounds but was able to stay in the air.

Meloy crawled to the location of the wounded company commander and first sergeant. Both were severely injured and sinking fast. Meloy decided to try to get a helicopter in under fire to evacuate them. Later he would call the decision “dumb decision number 2,” but he knew it was the only chance for Captain Henderson and First Sergeant Sam Solomon.

“I called Hornet, the 116th Assault Aviation Company supporting us, and almost immediately two gutsy warrant officers volunteered and came in through a hail of automatic weapons fire,” Meloy said. ”When the chopper flared to land, there was a huge explosion and it fell like a rock.” One of the helicopter crewmembers was killed, and another had a broken leg, but the two pilots got out of the wreckage without injury.

“Henderson saw it happen,” Meloy added. “He looked at me as if to say, 'Thanks for trying,' and died. Solomon painfully raised himself on an elbow, shook his head at the bravery of the pilots, and then sank down, dead.”

Meloy knew he had to get Company C reinforced as soon as he could. He ordered Company A, under Captain Richard D. Cole, to move by helicopter from its location at the Dau Tieng airstrip. He also ordered Captain Garrett's Company B to move overland to the fight from its blocking position location to the northeast. A/1-27 Infantry made its move, and by 1245 had tied in on the right flank of C/1-27 Infantry.

Gen. DeSaussure, the brigade commander, countermanded the order for Company B to move, but he ordered Company C, 3d Battalion, 21st Infantry under Captain Russell DeVries to move his unit by helicopter from the base camp at Tay Ninh. C/3-21 Infantry made the move in two stages, first going to the air strip at Dau Tieng and then on an LZ in the vicinity of 1-27 Infantry. The lead element of the company linked up with the Wolfhounds about 1445, and the entire company was on the ground by 1515, when Meloy ordered the unit to join the attack on the right flank of A/1-27 Infantry.

The brigade commander also ordered two companies from 1-2 Infantry to reinforce 1-27 Infantry. Under the command of Major Ed Stevens, the 2-1 Infantry operations officer, the two companies were airlifted from their positions on Axis Red. Meloy was not advised that the two companies had been put under his command or that they were on the way. “I didn't know it until they were on the ground and contacted me by radio,“ said Meloy.

With C/1-27 Infantry in reserve, Meloy enveloped and captured the VC base camp with Captain Cole's A/1-27 Infantry and C/3-21 Infantry under Captain DeVries. This had been accomplished by the time the two companies from 2-1 Infantry arrived about 1800. Meloy incorporated the two new units into his night defensive position. His command, now grown to five rifle companies, spent a relatively quiet night, with a few minor enemy probes but no real attacks. It was probably just as well. At this stage of the battle, Meloy's artillery support was barely adequate. He had brought his artillery fire-support coordinator, Captain Bart A. McIlroy, with him when he reported to the 196th Brigade, and his direct support artillery battery, A Battery, 1st Battalion, 8th Artillery was on call. But the battery's 105mm M2 howitzers had a maximum effective range of 11 kilometers, and the Wolfhounds were operating near that maximum range. A request for reinforcing fire from the 196th Brigade artillery was initially turned down.

The next morning, the assistant brigade operations officer showed up at Meloy's command post with a map detailing the continuation of the operation. The two companies from 2-1 Infantry were to move overland about three kilometers and resume their original attack on Axis Red--due east of the area where C/1-27 Infantry had fought the previous day. Meloy was ordered to attack northeast toward an arbitrary location on LTL 19, the so-called Ghost Town Trail. There he would link up with his Company B, which would attack to the west from the blocking position it occupied.

Meloy wanted to avoid any friendly-fire incidents in the thick, forbidding terrain. He gave Major Stevens and the two 2-1 Infantry companies a two-hour start before he set his two Wolfhound rifle companies in motion to the northeast.

“We ran into a VC concrete bunker complex. It was the only time I saw such fortifications in Vietnam, “ said Meloy. “The positions were manned by the 273d VC Regiment, and they immediately tried to outflank us. The fire was so heavy that everyone in the battalion command group except one radio operator was wounded.”

Meloy met the flanking maneuver by placing his units into a horseshoe-shaped defensive position, ”With my A Company on the right from 12 o'clock to 3. A platoon from Company C covered from 3 to 4. On the left, C/3-21 Infantry was deployed from 12 to 9, and the other two platoons from Company C were positioned from 9 to 7.”

Meloy immediately got in contact by radio with Major Stevens, who was commanding the two companies from 2-1 Infantry, and asked him to return. Stevens turned around immediately. The companies took some casualties on the return, but, as soon as they had closed on his position, Meloy deployed the two companies on his right flank.

Communications with the brigade were a nightmare. Initially, Meloy could not reach the brigade TOC at Dau Tieng, using his AN/PRC-25 radios, which had short antennas. The antennas worked fine for short-range ground and air-to-ground communications but could not reach the Dau Tieng base. Meloy dealt with the problem in a couple of ways. He was able to use the Air Force Forward Air Controller (FAC) to provide aerial relay of messages, and the Wolfhound assistant S3 at the rear command post managed to commandeer a helicopter for aerial relay. “And my operations sergeant, Roy Burdette--under heavy machinegun fire--assembled and raised a 292 antenna that enabled me to talk directly to Dau Tieng,” Meloy added.

Meloy's next surprise was a radio call from Lieutenant Colonel William C. Barott, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 27th Infantry, informing him that his battalion had been sent to reinforce 1-27 Infantry, that the lead unit would arrive within 10 minutes, and that Barott was accompanying the unit. General DeSaussure, without informing Meloy, had sent 2-27 Infantry. The first company to arrive was Company C, which had at first been sent to replace Meloy's A/1-27 Infantry as the airstrip security unit at Dau Tieng.

Hastily, Meloy assigned Barott a landing zone about 2 kilometers west of his horseshoe perimeter. He told Barott to move the company due east until it crossed an open field, then to turn due north into the 1-27 Infantry position. “It was a major mistake on my part,” Meloy said later. “It violated Murphy's Law—anything that can be misinterpreted will be. I should have given him azimuth directions, instead of Cardinal directions—to move on an azimuth of zero-niner-zero, then three-six-zero.”

C/2-27 Infantry and the battalion command group were on the ground and moving by 1440. For more than two hours, the unit moved through dense jungle. Instead of moving east and then north, Barott and C/2-27 Infantry, commanded by Captain Gerald F. Currier, went north and then east. The move put the company between Meloy's defensive horseshoe and a hornet's nest of oddly configured enemy positions, with well-concealed fields of fire. C/2-27 came under heavy fire from the enemy positions, and the company commander ordered an assault. The attack failed, and Captain Currier was killed. At this point, at about 1730, Lieutenant Colonel Barott threw a smoke grenade to mark the company location for an overhead FAC, who determined that C/2-27 Infantry was about 100 meters from the 1-27 Infantry positions. Barott took a squad, and set out for Meloy's location, but he was instantly killed by a burst of automatic weapons fire, and a number of others were killed in action in the firefight.

Meanwhile, the rest of 2-27 infantry began arriving. B/2-27 Infantry was the next company to reinforce Meloy's burgeoning command. It was near nightfall by the time A/2-27 Infantry arrived. Meloy incorporated these additional units into his defensive scheme.

The predicament of C/2-27 came to Meloy's attention when a radio-telephone operator named PFC Bill Wallace reported that the unit had tried to get to the 1-27 Infantry position, and that both the company commander and the battalion commander had been killed.

Meloy knew he had to get help to the stricken company as soon as possible, but the location of the unit created its own set of problems.

“It hampered our ability to call in artillery fire to our front and restricted full use of firepower by the rifle company opposite them,” he said. “Friendly fire was overshooting the enemy bunkers and landing in the C/2-27 Infantry position. I had a gut feeling the enemy did not know the precise location of C Company, and I imposed a strict cease-fire on them for fear they would reveal their exact position.”

During the night, the enemy probed the position three times, but the unit maintained their fire discipline and did not return fire. Meloy made two attempts to relieve them. During the hours of darkness, he ordered C/2-1 Infantry to make a night attack through what appeared to be a gap in the enemy's lines, but the attack was repulsed with five dead and eight wounded.

Then at first light, he ordered A/2-27 Infantry, under Captain Robert F. Foley to attack through what appeared to be another gap to the front. But there was no gap, and an intense firefight took place. Foley's heroism earned the Medal of Honor there, as did that of PFC John F. Baker, Jr., a member of his company.

The battered C/2-27 Infantry was relieved in place about noon on 5 November by B/1-27 Infantry under its determined and resourceful commander, Captain Bob Garrett. After Company B had been halted by Gen. DeSaussure on the previous day, Garrett had joined company with two units from the 196th Brigade--A/2-1 Infantry and A/4-31 Infantry. Both of these companies were accompanied by the battalion command groups of their respective battalions.

On the morning of 5 November, Garrett told the two battalion commanders he was moving “to the sound of the guns” to reinforce his battalion. The two commanders initially agreed to take their companies and go with him. Garrett proceeded to move his ad hoc task force southward toward his parent battalion. The two battalion commanders and their two companies initially went with him, but before the force reached the battle area, they decided to return to the east with their command groups—either on orders from Gen. DeSaussure, or on their own initiative.

“Oddly enough, they left their two companies with Captain Garrett. I never did figure that one out,” Meloy said.

The addition of the two companies brought the number of companies under Meloy's command to eleven. After coordinating artillery fire with Garrett, Meloy ordered him to attack to the south to relieve C/2-27.

By noon, Garrett and his task force had accomplished the relief mission, sustaining only one casualty enroute. At this point, Meloy directed Garrett to recover the wounded and evacuate the remainder of the company around the right flank of the enemy position and then to head south into the 1-27 Infantry defensive position. The movement was completed by 1600 hours on 5 November.

Earlier that day, Meloy had received a visitor who had suddenly flown into the position. It was Brig. Gen John R. Deane, assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division. Meloy briefed him on the tactical situation, and the general departed. Later in the day, Maj. Gen. William E. DePuy, commanding general of the Ist Division, appeared and asked Meloy if he really had eight companies.

“I told him that, since I had briefed General Deane, I had been given three more and was now up to eleven,” said Meloy. The astonished division commander told Meloy he wanted to relieve his force with a brigade from the 1st Infantry Division. DePuy also asked about the largely nonexistent command and control exercised by the 196th Light Infantry Brigade during the battle to this point.

In response to a question about how long it had been since Meloy had talked with Gen. DeSaussure on the radio, Meloy told DePuy it had been at least 48 hours. “Then he asked me when was the last time I had personal contact with DeSaussure, and I told him it had been on the evening of 2 November at Dau Tieng, when I got in a heated discussion with him about the original tactical plan.”

Gen. DePuy went on to ask questions about Meloy's contact with the brigade Tactical Operations Center. “I told him that I had seen the Brigade assistant S3 on the morning of 4 November and that was the only contact throughout the engagement. DePuy also wanted to know if I had asked for all of the reinforcements that had appeared, seemingly out of nowhere, and I told him that I had requested some of them, but most had just reported in piecemeal on my command radio net.”

That marked the end of Phase II of Operation Attleboro, and the beginning of Phase III. The relief of Meloy's force had its own set of problems to solve. He had to figure out how to break contact with the enemy and withdraw to the south through the 1st Division units deployed to the rear of his position.

“Five of my companies were still in direct contact--within 20 meters of the enemy--so it was impossible to withdraw without their knowing it. The first thing I did was send the six companies that were not in contact to the rear, where they were later picked up by helicopters for movement to their base camps. Then came the tricky part--breaking contact on the ground,” Meloy added.

He decided to pull the companies back one at a time. “First, I had the artillery ready to shoot on my command directly into the defensive positions,” he said. Then he called the company commander for notification the instant the company was ready to move. When the commander reported, “I told my artillery fire-support coordinator to fire. As soon as he said '”Shot,”' indicating rounds on the way, I ordered the company commander to go.”

The artillery rounds had about 70 seconds of flight time. In that brief time, the rifle company pulled back about 50 meters, firing as they went. Then the rounds exploded on the position the company had previously occupied.

“I repeated the procedure until all of my companies were out of contact and had passed through the 1st Division's combat outpost line at the edge of the jungle,” Meloy said. “I don't think you'll find that tactic in any book, but it worked.”

After 5 November, the size of the enemy forces involved became apparent to the U.S. generals, and Phase III of Operation Attleboro took on an entirely different character. Operational control went first to the commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division, then to the commanding general of II Field Force. Before Attleboro was over on 24 November, all of the 1st Division, along with elements of the U.S. 4th and 25th Infantry Divisions, the 173d Airborne Brigade, and several South Vietnamese Army battalions had taken part in the operation--more than 22,000 U.S. and allied troops in all. It was the largest U.S. operation of the war to that time.

Major Sandy Meloy became the only American officer in the Vietnam War to exercise personal command over 11 rifle companies in combat. The textbooks on tactical doctrine will inform that such a thing far exceeds an individual commander's span of control--the number of subordinate leaders he can effectively control. But sometimes in infantry combat, the textbooks go out the window.

Copyright 2004 H.L. McAllister

How I Became a Wolfhound...

When I first learned that Maj. Gen. Sandy Meloy, one of the heroes of our regiment, had been selected to command a Wolfhound battalion as a major during the Vietnam War, I knew it was a story I had to tell. It took a while, but, finally, I got it out of him – and here it is – the whole story.

H.L. McAllister

22 March 2004

Dear Dutch,

Maj. Gen. Sandy Meloy

A while back you asked how I, as a major, ended up commanding the 1-27th Wolfhounds. That's a good question, since it's an unusually strange story. To tell it right, it's also a long story.

It actually starts in 1964 when I was on the faculty at the Army Command and General Staff College teaching Joint Airborne Operations. We taught in three-hour blocks, and over the period of several months managed to present instruction to perhaps half a dozen different student sections, each with about 50 officers. By Christmas, each section may have seen as many as 25 to 30 different instructors. Just before Christmas--in one of the chiseled-in-granite customs probably dating back to Eisenhower's days at Fort Leavenworth--each student section selected a faculty member to be an honorary member of the section. Among both students and faculty this was considered a significant honor, but it also imposed certain responsibilities on the instructor. For one thing, he had to attend every section party. And since CGSC students could cook up a party for the flimsiest of reasons imaginable, there was a lot of after-duty socializing. By the end of the academic year in June, the honoree knew every member of that section well, and vice versa.

In the 1964-65 academic year, I was selected as the Honorary Member of Student Section 14. An armor major named Earle Denton was a member of Section 14. Remember that name.

In the summer of 1965, I volunteered for Vietnam. I was anxious to get into action before the war was over--which I suppose proves I am not exactly a paragon of prescient forecasting. In November 1965, I received orders to report 1 February 1966 to the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) as an advisor to the Vietnamese Airborne Division.

I was subsequently assigned as the US Advisor to the Airborne Division's Task Force One, replacing Norm Schwartzkopf, with whom I became a good friend. The division was organized with two Task Force Headquarters, and at that time there were seven airborne infantry battalions, but no artillery, so we depended a lot on 60-mm mortars and close air support. Each Task Force was the equivalent of an ARVN regiment. We usually deployed with three airborne battalions, but, because of the task force concept, the battalions were not necessarily the same battalions from one deployment to another. We were considered the ARVN “fire brigade,” so we moved around frequently among all four ARVN Corps areas.

Each battalion had three advisors: a captain, a lieutenant, and a senior NCO. There was a single advisor at task force level, and I was it. I had no assistants, but the Vietnamese did provide me with a radio operator. Mine didn't speak a word of English, but after a lot of semi-comical coordination between the two of us, he did recognize my call sign--Red Hat Alfa.

My first operation came three weeks after I arrived when we conducted a three-battalion airmobile operation in the dead center of War Zone C. We moved around War Zone C for almost a month, got into lots of fights--most of which lasted less than an hour before the VC faded into the jungle. Since it was the dry season, we drank an awful lot of "B-52 water" from the bottom of a zillion bomb craters.

Shortly after we returned to home base outside Tan Son Nhut, I was informed by the Detachment Adjutant that I had been selected for LTC, but "you're so far down the list, don't get excited."

After a couple of R&R weeks in the Saigon area, Task Force One was next sent to Hue to put down a "revolt" by the 1st ARVN Division, then two weeks later deployed to the Bon Song area in II Corps to work with the (ugh) ARVN 22nd Infantry Division. Again, a heck of a lot of enemy contact, but nothing worth writing home about, I suppose.

On the 29th of July 1966, while the Task Force was in a serious fight, I was startled to hear on my tactical radio net the voice of the Airborne Division's senior advisor, Colonel James B. Bartholomees (USMA 1942). Bartholomees seldom ventured outside the Saigon city limits, and to my knowledge had never visited task force or battalion advisors, most of whom were spread all over Vietnam with deployed ARVN airborne units. I had not seen him in almost three months, so hearing his voice was a surprise, especially when he said he wanted to land (he was in a helicopter) and talk to me. Since we really had not had that much contact, his wanting "to talk to me" sounded ominous.

I advised him we were in contact and suggested he come back in an hour or so when I could secure a LZ. An hour or so later he returned, landed, and I ran over to report. With not a "How are you?" or other preliminaries, he told me, "Get your gear, I'm here to take you back to Saigon."

I was stunned. He kept pointing to the helicopter, but I insisted that I really ought to let my counterpart, a lieutenant colonel named Ho Trung Hau, know where I was going. I also wanted to discuss with Ho Trung Hau which of the three battalion advisors he preferred as my replacement, and I wanted to notify whoever that was to get his butt in gear. But after saying goodbye to an equally stunned Colonel Hau, I picked up my rucksack and climbed aboard. Bartholomees never said a word. He was obviously agitated and disturbed about something. I figured I'd been relieved, but I didn't have a clue as to why.

When we got to Qui Nhon, we boarded a twin-engine U-21 and flew to Ton Son Nhut. Bartholomees still hadn't said anything. After we had been in the air for about 30 minutes, I asked, "Colonel, have I been relieved? If so, I'd appreciate knowing why."

He didn't say anything right away, then suddenly asked, "Do you know General Weyand?"

I said, "No, sir, I never heard of him."

He next asked, "Do you know Colonel Tarpley?"

"Never heard of him, either.”

"What about Colonel Mellon?"

"Nope, who's he?"

He looked at me as if he didn't believe me. "You mean you don't know any of those officers?"

"No, sir, should I?"

After a lengthy pause, one so long I began to fidget, he said, "Well, I pulled you out of the field because you're going to the 25th Division."

When he said that, I honestly assumed he was referring to the ARVN 25th Division, a division that even General Vien, then the ARVN Chief of Staff, claimed publicly was perhaps the worst division in Vietnam. It was probably the worst division in the free world.

I asked, "Sir, what did I do to deserve that?"

He replied, "You mean you don't want to go to the 25th?"

"Heck no!"

"Sandy, I don't think you understand. I'm not talking about the 25th ARVN Division. I'm talking about the 25th U.S. Division."

Whoa!! My first reaction to that was not "Thank God!" but "Why me?" I assumed since I was just a major, that meant a staff job. I already had what I considered one of the best jobs any major in Vietnam could have. I had great respect for the Vietnamese airborne troopers, who not only knew how to fight, but at times seemed to go out of their way to find one. I had enormous personal and professional admiration for my counterpart, LTC Ho Trung Hau, who was the most highly decorated battalion commander in the ARVN, spoke flawless English, and whom I considered a good friend. Frankly, I much preferred working with Task Force One than serving as a battalion or brigade staff officer, and I so advised Colonel Bartholomees.

"Sir, if I can change this assignment and get out of going to the 25th, can I stay in the ARVN Airborne and will you let me return to Task Force One?"

For the first time, he smiled. "Sure, that's fine with me, but I've already tried to break your assignment, and couldn't do it. If you think you can, you're welcome to try."

Early the next morning (30 July), I went to USARV Headquarters with a chip on my shoulder. I was determined not to take “no” for an answer. The MP at the reception desk told me where to find the personnel section, and there a sergeant told me where to find the field grade assignments office. I found the right room and burst through the door. Sitting at the first desk was LTC Earle Denton, my old buddy from CGSC Section 14. I hadn't seen Earle for almost two years. He looked up, and when he saw me standing there, he said, with an ear-to-ear grin, "Hi, Sandy. I've been expecting you."

"Don't give me that nonsense. What are you trying to do to me? I do not want to go to the 25th Division. I'm happy right where I'm at, so please don't do me any favors. I would appreciate it if you'd cancel those orders and let me go back to my advisor's job."

I think I also said "please" and "thank you" a couple of times, but my message was clear. Denton just kept smiling and waited until I ran out of breath. He told me, ”Sit down, you dummy" and proceeded to say, "You're going to the 25th to command the 1st Battalion of the 27th Infantry. They are called The Wolfhounds. Do you still want me to cancel your orders?"

I just stared at him. "But Earle, I'm only a major."

He laughed. "Do you think I don't know that? As a matter of fact, I'm not only sending you to the 1st Wolfhounds, but also I'm sending another major, a fellow named Bill Barott, to command the 2nd Wolfhounds.

This is how Earle Denton explained the sequence of events and why two majors instead of two lieutenant colonels were selected to command the two Wolfhound battalions.

The officer who had commanded the 2-27 Wolfhound battalion for most of the first six months in the war was LTC Boyd T. Bashore, USMA 1950. Bashore apparently was a fine battalion commander, but his command tour was coming to a close. General Weyand, the commanding general of the division, wanted to make him the G5. Therefore, the 2-27 needed a new battalion commander.

The case of the 1-27 was much different, and, in a real sense, rather tragic. The commander who brought the battalion from Schofield was relieved for cause, and he was replaced by a grand old warrior named Harley Mooney, who later became the G2 of the 25th Division. The next commander of 1-27 was also relieved for cause after a badly botched operation with heavy US casualties on 19 July led to his relief.

Apparently, there were no other suitable lieutenant colonels available in the 25th, so Colonel Mellon, the Division Chief of Staff, requested USARV to nominate qualified lieutenant colonels. And this is where Earle Denton entered the picture.

General Weyand's criteria were straightforward and reasonable. He wanted commanders who met three basic qualifications – those who had plenty of troop duty experience, were graduates of the Command and General Staff College, and had already earned a Combat Infantryman's Badge. With that guidance, Denton went to work evaluating the personnel records of lieutenant colonels in USARV. And that's where it got interesting.

The first four lieutenant colonels Denton queried said essentially the same thing, "Gee, Earle, I'd just love to command a battalion, but I just don't see how I can break loose from this extremely important project I'm on right now--later, maybe. Thanks anyway."

Earle told me that he approached at least half a dozen others, but their stories were similar: "Can't do it now--maybe later." In frustration, Earle submitted the best ten names he could identify to Mellon, but for one reason or another General Weyand turned them all down, so it was back to the drawing board. He tried several more times to nominate others who met Weyand's criteria, but got nowhere fast. Either those nominated had an excuse for not being immediately available, or Mellon and/or Weyand rejected them. Denton was fast running out of candidates.

At this stage of the war, General Westmoreland had a firm policy prohibiting MACV officers from being transferred to USARV units. Westmoreland believed that stability and continuity among advisors was essential; hence he froze MACV advisors. Given the situation in the 25th (by this time 1-27 had not had a battalion commander for more than two weeks), Weyand was growing desperate. He apparently knew Westmoreland well enough to call directly and request an exception to policy. Westmoreland finally agreed and told his MACV staff that for battalion command, but only for battalion command, it would be okay to transfer MACV officers to USARV.

This gave Denton a fresh start. He used the same criteria, and was able to identify several qualified MACV lieutenant colonels. But once again, Weyand and/or Mellon rejected Denton's nominations. Growing more and more frustrated, Denton asked Weyand if he would consider "promotable majors." Weyand, who I suspect was equally frustrated, said okay.

Denton returned to MACV, got a list of majors whose names were on the promotion list to lieutenant colonel, and Bingo! One of the first names he saw was one he remembered from Leavenworth, the 1964-65 Honorary Member of Section 14, Sandy Meloy, who, to Earle's relief, met each of Weyand's criteria. Earle also knew Bill Barott. Denton took the record files and returned to the 25th Division, laying our records on Weyand's desk. Weyand had been Bill Barott's commander in the Berlin Brigade in the late 1950s, and he knew and liked him, so selecting Barott was easy. But he didn't know me from a hole in the ground. He asked if any of the staff did. Colonel Mellon said, "I don't know Meloy personally, but I do know a little bit about him.”

Colonel Mellon had commanded a Battle Group in the 1st Cavalry Division in Korea in 1961-62. At that same time, I commanded a mechanized company of the 8th Cavalry in the DMZ. Having one of the only two mechanized companies in Korea at the time, my company was often tasked to act as the Aggressor force against different Battle Groups undergoing the annual proficiency tests then known as Army Training Tests, or ATTs. One of these Battle Groups was commanded by Colonel Mellon, who apparently thought my company had done such a fine job that five years later he told Weyand, "good guy, take him." And, on only that faint recommendation, Weyand decided to assign me to command the First Wolfhounds.

So, that's an awfully long way around to answering your question, but is does have some interesting teaching points: 1. You never know when people who know you might play a behind-the-scenes role in your "career development." 2. It once again proves the old adage: it's not who you know, it's who knows you. 3. It doesn't hurt to be in the right place at the right time - this is known as dumb, blind luck. 4. It's even better to be in the right place at the right time when the main decision maker is starting to get desperate.

I spoke with Earle Denton on the morning of 30 July 1966. That afternoon I rushed around Saigon to clear out of MACV and make sure the Finance guys in USARV knew who I was. At that time we still had manual one-soldier-at-a-time paydays, and the next day was payday. At 0800 on the 31st at the Hotel 3 helipad at Ton Son Nhut, Command Sergeant Major Jack Eakins picked up me and my beat-up duffle bag, and we flew in a Little Bear helicopter to Cu Chi. At 0900 I reported to Colonel Tom Tarpley, the Commander of the 2nd Brigade. At 0945 General Weyand came into Tarpley's office, introduced himself, and cautioned me never to maneuver beyond artillery range. I had just spent five months in the boondocks without any artillery of any kind, so that was happy news to me.

At 1000 there was an "assumption of command" ceremony in which Hal Myrah, the battalion executive officer and a West Point classmate, officially welcomed me to the 1st Battalion of the 27th Infantry. At 1030 I was briefed on two items. The first was Kolchak, the regimental mascot. The First Battalion was guardian of the regimental colors, and it was our duty to maintain this moth-eaten dog, which had just devoured some woman's prize cat in Hawaii. I was informed that, as the battalion commander, I was being sued for damages. The second item of briefing had to do with why and how the troops had contributed more than a thousand dollars to the Wolfhound Orphanage in some strange-sounding place in Japan. Knowing first sergeants, I did not believe it was done voluntarily, so I walked about talking to soldiers at random and, to my astonishment, I discovered it was, indeed, voluntary.

At 1230 I was re-introduced to American food, which sure beats boiled rice and boiled chicken three times a day. At 1330 I startled everyone by calling out the Division Alert Company, which, on that day, happened to be Alfa Company, 1-27 to let the soldiers know immediately that I expected them all to carry extra dry socks, clean ammo, two full canteens, insect repellent, and water purification tablets. At 1500 I sat down with the S2 and S3 and planned the next day's operation, which was a battalion-size airmobile assault into the village of Trung Lap. At 1600 we briefed the company commanders and artillery battery commander on the next day's operation, incorporated several of their suggestions, and issued the final order. Just before dark, I was shown my hooch. I went to bed with a big smile.

That's the long answer. The short answer is I held a golden horseshoe and didn't know it.