School of Hard Knocks on the Cambodian Border

The following stories are how two Wolfhounds in the Second Battalion remember the fighting associated with the establishment of Patrol Base Kotrc, a tiny fort near the Cambodian border.

FIRST DAY IN THE WAR is Richard Hamilton's story of his ungentle introduction to combat as a rifleman in A Company. This is followed by BUILDING A PATROL BASE – THE HARD WAY by Major Charles Darrell, who was executive officer of the battalion, and who assumed command after the battalion commander was wounded. Finally, in TAKING THE WAR TO THE ENEMY, Richard Hamilton recounts his further adventures in the days after PB Kotrc was built.

First Day in the War

by Richard Hamilton

August 12, 1969

Fire Support Base Jackson, Vietnam

I was one of about seven "newbies" who arrived at Fire Support Base Jackson on August 11, 1969. We were assigned to Alpha Company when the unit arrived there later that day. We met the First Sergeant and the company commander. Captain Penn made at least one very scared GI feel much more comfortable.

The next morning, the first lift left for our new location and immediately ran into trouble. Back at FSB Jackson we were listening on the radios and were not encouraged. Eventually, the whole company was inserted, as well as Delta Company and a part of Charlie Company.

My squad, although part of the first platoon, was initially left behind to provide security at the helicopter pad at FSB Jackson during the morning. When we were finally lifted out, as the last body on the "slick," I sat with my feet hanging out of the open door. When we arrived at the hot landing zone, I could see two downed Hueys, one marked with the red crosses of a Dustoff helicopter.

Our LZ was about 200 meters from some higher ground, and the downed helicopters were about halfway between. The high ground rose from a marshy area, and there were rough, dense hedgerows. The contact area was roughly the size of 3 to 4 football fields, and the scene of great pyrotechnics and firepower. The area literally shook from end to end from the attacks of the A4 Phantoms, with their napalm and bomb strikes. Helicopter gunships were making their runs, and I remember a Huey coming over with a 55-gallon drum slung underneath (filled with jellied gasoline and called a "Flame Bath"). The drum was dropped on the NVA bunker. There was a lot of artillery falling into the area.

I was lying in about 8 inches of water and I pressed my face into a clump of swamp grass. Bomb and artillery fragments were falling around us, and the hot fragments hissed when they struck the water. The noise was deafening. After five or ten minutes, a sergeant or lieutenant sloshed over and told several of us to go forward and provide covering fire and assistance to men who were hunkered down behind the downed choppers.

As we went forward, I was thinking how it seemed so surreal, like I was dreaming the entire scenario. When we got to the helicopters, I noticed a dead grunt with a head wound floating face down; he was a big guy – and I am not – I grabbed one ankle and someone else grabbed the other. We were half crawling as we got him back to our line. Another lift was arriving, and after the men jumped out, we put the dead man in the Huey and it left. I never did know who he was.

After about an hour, the word passed down the line that we were going in. I believe the major, who was down the line to my left, decided it was time to attack. I was comfortable behind my small clump of grass and loathed to leave it, but I didn't want to be left behind alone. I grabbed the can of M60 ammunition I had carried from FSB Jackson and started out. After about 6 steps, I tripped and fell forward, dropping my M16 and the can of ammo. By the time I had cleared my rifle and looked up there was no one in sight. Not good.

I scrambled forward and came to a slight rise at the edge of the marsh. As I crawled over the top, ahead of me was an NVA soldier, completely covered with mud, half sitting, facing me. I swung up my rifle instinctively, but stopped when I realized he was dead – apparently killed by a bomb or artillery round. His head was split down the middle, with half resting on each shoulder. This had not kept a number of the soldiers ahead of me – who were also running on PURE adrenalin – from stitching him as he came into view. A real mess.

Anyhow, I finally caught up with the line and up the hill we went. I couldn't believe anyone could be alive here, but off to my right a grunt took a round in the ass from a well-concealed spider hole. Someone asked for a frag, and I slid one over to him. A few of us kept firing at the trap door until he got behind it. He waited until it raised a little and threw in the grenade. It must have been a fairly deep hole as all that was heard when the grenade went off was a little 'whump'. After a few more minutes we were in control of the area, and I found out, to my surprise, that I was with Delta Company. I had no idea where Alpha Company was, but a sergeant told me not to worry about it. It was getting dark, and I was not going out to look for them. Delta's hospitality was fine with me. We began digging in for the night.

A Spooky (surveillance helicopter) was overhead all night, but there was no activity. The next morning I remember slicks from Cu Chi bringing in water bladders, Mermite cans filled with hot steaks, and ammo cans filled with loaded M16 magazines. I heard later that admin REMFs were up all night filling the magazines.

I located Alpha Company and was glad to learn that I had not been reported missing in action (not something I wanted my Mom told). I guess I was so new to Alpha, no one knew to miss me. My first day in the war was over.

©1999, Richard Hamilton

Building a Patrol Base – the Hard Way

by Major Charles Darrell

August 12, 1969 Fire Support Base Jackson, Vietnam

Lieutenant Colonel William E. Ebel was a big, tall, good-natured man. He ordered me to build a fort on the Cambodian border. Nine slicks were to transport Captain Charles Varence Penn's Alpha Company to the site in two lifts, starting at 0700. Cargo helicopters would bring in 17 loads of supplies and we'd build the fort. One company from the South Vietnamese 50th Infantry would join us later, and we'd run combined operations from there.

The air was very heavy. We poured sweat as we formed up in the flat field outside Fire Support Base Jackson's wire. The helicopters showed up at 0700, but there were only four of them. There was no time to argue. Captain Penn, PFC Canfield (Penn's radio man), Lieutenant Roberts (artillery FO), and I jumped on the lead helicopter with two other men. Eighteen men piled in the remaining three slicks, and we headed west. From the air, the wide expanse of rice paddies below looked peaceful. We touched down in a rice paddy, vicinity grid coordinates XT377144, jumped out, and rushed for a tree square. The sun was in our faces. Two twisted and blackened tree stumps stuck out at odd angles near our position. I sensed that we were being shot at before I heard the sound. Lieutenant Roberts fell on his face. A brief spout of blood shot from his left temple. Canfield, hit in the stomach, took one step and fell flat. We dove behind a paddy dike and pulled Canfield and Roberts to cover. We were lying in a foot of water. Penn took Canfield's radio and I took Roberts's. We couldn't see the enemy, but they were close and firing at us from three sides. I called for artillery fire behind the enemy and adjusted it toward us by ear. Frank Leach, the battalion S-3, got helicopter gunships. I told them to circle in from behind us, so they wouldn't have to fly through the artillery trajectory and we could keep the artillery coming. I didn't want to lift it.

Lieutenant Graul, Sergeant Naputi, and the rest of Alpha Company landed 400 yards to the west, out of the crossfire. They crawled forward to our position. "We can't see where we're going," said Graul on the radio. "I feel like a mole!"

We lobbed grenades over the paddy dike, kept heads down, and tended the wounded. I pulled down Canfield's trousers to look for an exit wound. There wasn't one, but he had crapped in his pants. Aaron Smith let out a weak groan as I applied his bandage to a protruding brownish gray coil of intestine.

I needed to put the artillery right on top of the enemy without killing my own men. "When you see the smokescreen," I said, "grab a body or weapon and move 100 yards to the rear." Major Bob Greene flew in about 10 yards off the deck and put down a perfect smokescreen. He took several hits.

Penn and I grabbed Canfield under the arms and hustled to the rear. We each had a radio as well, and we fell every few steps. All six wounded soldiers were pulled back.

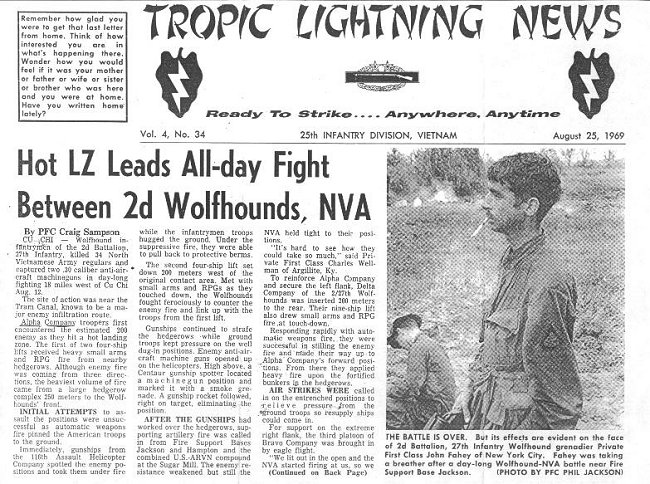

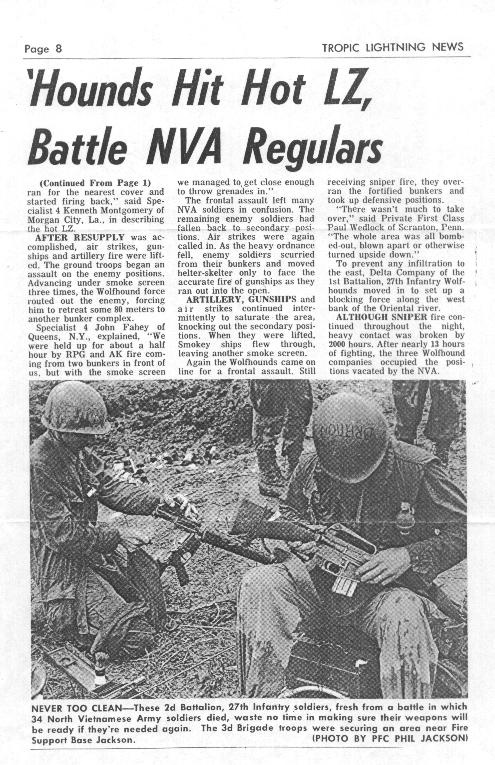

Bodies and weapons were left behind. Captain Penn, PFC Dixon and I crawled back three times. We pulled the dead to cover first, and then recovered the rifles. We were totally exhausted. Weariness more than fear made it hard. Now, artillery from all over was falling on the enemy with loud whooshes. Spent shrapnel splashed in the paddy water. In that one day, the six-gun battery of 105mm howitzers at FSB Jackson fired 3000 rounds. Brigade Commander William J. Maddox, flying his own helicopter, put in 17 airstrikes. The planes dove low through the clatter of small arms fire to drop napalm. The bombs drifted in slowly with a rushing sound. Sometimes we could feel the heat. "It's hard to see how they could take so much, " PFC Wellman of Argillite, KY told a reporter later. The enemy fire seemed to slacken.

Three helicopters responded to my call for medevacs. One made it in and picked up Canfield, who would survive, and Smith, who wouldn't. Two other helicopters were shot down. The crews joined us on the ground.

Around 1500, Colonel Ebel arrived with Delta Company and a platoon of Charlie Company. He crawled forward to take command. I rushed over to brief him, but he was hit as he reached the two downed helicopters. Four shirkers were hiding under one of the helicopters. I pulled my pistol on them. "Get a stretcher out of this helicopter and carry Colonel Ebel back there, " I said, "And if you drop him, I'll shoot every one of you myself."

We dragged the rest of the wounded and dead farther back where they could be evacuated, and it shames me now to think that I did not know any of their names. The shirkers faked wounds and climbed on the helicopters. I would see they got theirs later.

By 1600, it felt like the enemy fire had been suppressed enough for us to get in on top of them. I asked Greene to put in another smoke screen and I shifted the artillery. Penn and Alpha Company assaulted the tree square to our right (south), "We were held up by RPG fire and AK fire coming from two bunkers in front of us," said SP4 John Fahey of Queens, NY, the next day, "But with the smokescreen we managed to get close enough to throw grenades in." Jay Yurchuck and Delta Company attacked the tree line to our front (east). Lieutenant Kaui's C Company platoon advanced on the bunkers to the left (north). I went in with Yurchuck's company. "If you get hit, sir, who's in command?" asked Colonel Ebel's radio man.

"You are, for awhile, " I replied.

"Then don't get hit, sir," he said.

Gunships fired 10 yards to our front. "They're shooting us!" shouted Lieutenant Faircloth.

"You're hitting us," I radioed the pilots. "Lift it a little, but keep it close."

"They're trying not to hit you, " radioed Colonel Maddox.

"They're doing great," I responded.

A couple of Delta Company's M16s exploded because of water in the barrels. It wouldn't drain out with a round in the chamber.

Lieutenant Faircloth stepped over a dead enemy soldier and into the treeline. Lieutenant Kaui's men advanced slowly. "You have got to keep your men moving!" I radioed. "We're receiving flanking fire from your front!"

"He's doing the best he can," Colonel Maddox broke in. "Let me get a couple of gunships over there." That's all Kaui needed.

In the tree squares, it was face-to-face. The enemy fought to the death, but we took the ground. "There wasn't much to take over, " said PFC Paul Wedlock, of Scranton, PA. "The whole area was all bombed out, blown apart, or otherwise turned upside down." We pulled North Vietnamese corpses from their holes and stacked them. Villagers would see to their burial. Captain Anderson pulled a blue and red ribbon from a dead man's chest and pinned it to his jungle hat.

It was getting dark. We formed a perimeter and I considered sending out a listening post. "Sir," said Sergeant Hurley of Alpha Company, "We'll need every man on the perimeter tonight." On April 15, every last man in a listening post had been killed when the North Vietnamese attacked Patrol Base Diamond III. Hurley wanted me to know that, if I gave the order, I would have to force the men to obey. It was an easy decision. The troops had done good work and the five minutes' early warning we would have gotten from a listening post was not worth the risk. "We do need every man on this perimeter," I said.

The next day, Delta Company flew back to Fire Support Base Jackson, and Kaui's platoon flew back to Shamrock. Alpha Company began constructing the fort. Around noon, Colonel Maddox stopped by to see how the construction was going. I was glad to see him. He introduced Lieutenant Colonel Moore, who had once tried to teach me Mechanics of Fluids at West Point, a losing battle. I was glad he didn't remember me.

I described the battle and explained what we were doing. Colonel Moore walked the perimeter and made some suggestions. He pulled out a map. "Maybe you should send a patrol down this stream bed tonight," he said.

His suggestions were reasonable, but the men were working slowly, and I expected an attack soon after dark.

"Sir, " I said, "Only one of us can do this. If you want to do it, I'll leave. Otherwise, please let me do it my own way."

He left. I didn't know it then, but he was my new battalion commander. The Vietnamese company did not join us until after the work was done. Their adviser was Bob Kramer. I later taught tactics with him at Fort Benning.

We named our little fort Kotrc, after Jim Kotrc, the Delta Company Commander who had been killed two weeks earlier at the BoBo Canal.

At the time, I did not even know the names of the men whose bodies I put on the helicopters after the battle, but the 25th Division yearbook gave to them and and to our other dead this epitaph from the Confederate War Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery:

Not for fame or reward

Not for place or for rank

Not lured by ambition

Or goaded by necessity

But in simple

Obedience to duty

As they understood it

These men suffered all

Sacrificed all

Dared all — And died

Thirty years later, I learned their names:

| Name | Rank | DOB | Hometown |

| Denny Ray Lappin | E-6 | 4/4/44 | Canton, OH |

| James Henry Marshall | E-4 | 11/8/49 | Selma, AL |

| Charles Dwaine Roberts | O-1 | 5/30/44 | Norman, OK |

| Aaron Bruce Smith | E-3 | 10/9/46 | Arkansas City, KS |

| Stephen Allen Snidow | E-3 | 7/12/48 | Ft Smith, AR |

| Millard Preston Wheeler | E-3 | 6/11/49 | Hamersville, OH |

One Vietnamese Kit Carson Scout, a defector from the VC, fighting on our side, was also killed. I do not know his name.

©1999, Charles C. Darrell

Taking the War to the Enemy

by Richard Hamilton

August 13-15, 1969

Patrol Base Kotrc, Vietnam

Delta Company and the platoon of Charlie Company were lifted out on August 13, and Alpha Company began construction of what would be later named Patrol Base Kotrc. There was a whirlwind of activity; big Chinook helicopters dropping bales of sandbags, pierced-steel planking, RPG screening material, rolls of concertina barbed wire, timbers, shovels, three 105mm. howitzers, 81mm and 4.2-inch mortars, with ammunition for all of them. There was even a preconstructed radar tower.

I don't recall working as hard in my life. Everyone in the company was hard at it, with officers (including the CO) and enlisted men digging bunkers and using the dirt to fill sandbags – it seemed like a million of them. We were all aware that a NVA attack was more likely in the early days before the base was 'hardened.' As part of the "Vietnamization" program, a company from the ARVN 25th Division joined us and were assigned to defend the eastern half of the perimeter.

We had to pay attention to things 'outside the wire,' and listening posts were set up. That night, six of us (Sergeant Ken Smead, Ken Lafaive, Stan Hildreth, myself and two others – perhaps including our RTO Bourque) left the perimeter about 2000 hours to a position about 150 meters in front of the ARVN side of the perimeter. The ground was pretty flat, but we found a slight rise and got set up. As scared as I was due to recent events and knowing the Cambodian border was just a 'click' away, I was dog-tired. We set up a guard rotation with two guys up all the time with the starlight scope and the radio, while the others slept.

About midnight, there was a series of two or three blasts about 50 meters east of us – shaking the ground and waking everyone up in a hurry. Mortar rounds from the enemy in Cambodia. After a few minutes, we heard more incoming . I've always thought incoming mortar rounds sounded like a flight of invisible birds – whooshwhooshwhooshwhoosh; also incoming rounds sound like they're coming right down your shirt, even when they land at a distance. This 'stick' landed about 50 meters to the west of us, between us and the perimeter.BLAMBLAMBLAMBLAM.

Sergeant Smead got on the radio. The company command post told him they thought the NVA was just getting the range for the patrol base, not targeting the listening post. Smead told them targeting or not, we had been bracketed. We were told to come back into the perimeter, and Smead reminded them we would be coming in on the ARVN side and to make sure the ARVNs were expecting us.

We needed no urging. We grabbed our gear and headed for the wire, bent over and running as fast as we could. Halfway there, we sent up a green star cluster. I hope they told the ARVNs, I thought. They had. The wire was opened, and we streamed in, not stopping until we reached the welcome confines of our bunker. More mortar rounds were falling near where we had been, and our own mortar men were outside in their pits throwing rounds back at the enemy.

After a few minutes, the incoming ceased, and we were sent back out again to a different location. The rest of the night was uneventful except for the fact that everyone was so 'pumped up' that no one got any more sleep.

During the next few days we got a good look at our area of operations. It was pretty much flood plain and abandoned rice paddy systems. Since it was still the rainy season, there was plenty of water. The paddies had 8 to 10 inches of water in them, and the water in the canals was deeper. The patrol base itself was on higher ground and included an old cemetery. The weather was hot and steamy during the day and surprisingly cool at night.

Often, it took a few minutes to limber up hands and fingers in the morning, when finishing up an ambush patrol. Of course, the fact that we were half-submerged in water along a paddy dike may have had a lot to do with it. However, it did not seem to slow down the leeches.

We set up claymores and trip flares along the Tram Canal, which ran about 100 meters from the perimeter. The canal's course meandered right into Cambodia. It was shallow, with heavy hedge growth on both sides, a natural infiltration route for the NVA. There was a natural trenchlike depression that ran in a crescent shape along the western side of the perimeter. More concertina wire was strung along the edge of the depression. The three 105mm guns were ready for action. I think the gun crews were from the 3/13 Artillery, but I'm not sure.

The second night following the mortar attack, I went on my first ambush patrol. The first, second, and third platoons – the rifle platoons – rotated AP duty. Two of the platoons went out on the patrols every night, and the other one manned the bunkers inside the wire. The 4th platoon, or weapons platoon, did not draw the AP duty, but they had to take care of some of the unsavory duties such as keeping the field latrines in order and burying NVA bodies.

As we were setting up on my first AP, I noticed an awful stench close by, but the darkness prevented checking it. There was no activity in the night. As I crawled forward to retrieve my claymore, I discovered the source of the smell. A dead NVA soldier was lying about 3 meters from where I had set my Claymore. He was opened up (gunship?) and was quivering from maggots. I puked off and on all the way back to the patrol base.

When we returned from the AP, the platoon had time for breakfast, writing letters, and cleaning weapons. Then about 0800 we set out on my first RIF, or reconnaissance in force. The platoon's route took us across the canal to the south, and we checked out several heavy hedgerow areas, without any contact with the enemy. I discovered I would have to exercise good water discipline on RIFs. I had brought only one canteen, thinking it would easily last me all day. The canteen was empty in about three hours.

Fortunately, Vern Ward, our 'dooper' man (M-79 Grenadier) took pity on a poor dumb newbie and shared his water with me. He carried three canteens.Humping the boonies was hot work, and the lesson was not lost on me. I acquired two more canteens.

We got back to the patrol base about 1600. This routine – a RIF and an AP each day, with a 'day off' every third day was how we operated for the next three months, when we were able to go back to Cu Chi for a 48-hour stand-down. Pounding the boonies wasn't easy, and it was dangerous, but once you caught on to its rhythm, it was in many ways more comfortable than pulling duty back at Cu Chi.

©1999, Richard Hamilton