The Diamonds – Wolfhound Country Forever

by Howard Landon McAllister

Lieutenant Colonel Daniel B. Wilson, the present commander of the Second Wolfhounds in Afghanistan is looking for a name for a “hardstand” away from the main Forward Operating Base. Wilson has a sense of history, and he wants to impart it to all of the warriors he commands. Jerry McKinney, the honorary sergeant major of the regiment, has put out a call for suggestions. In due course we will learn what Wilson has decided to call it.

It reminds us of a couple of things. One of them is the unbroken line of tradition that unites Wolfhounds. But something is changing. I cannot put my finger on it, but I sense it. I can remember Larry and Gini Milfelt as the only Korean War representatives at Wolfhound reunions. I know Larry is a Wolfhound who is as fanatical as I am. But on 17 July 2011, I had a conversation with Tom Donovan, a Vietnam Wolfhound, and treasurer of our historical society. He told me a wonderful story about how many young Wolfhounds and former Wolfhounds are attending reunions these days. Years ago, reunions were related to single wars, leading to the unhappy events once memorialized on U.S. postage stamps. I remember two of them from my own childhood, honoring the final encampments of the Grand Army of the Republic and the United Confederate Veterans of civil war days.

It is no longer true. Today the links with our Wolfhound past are reminiscent of the same spirit that animates the “Long Gray Line” at West Point. It warms an old soldier’s heart.

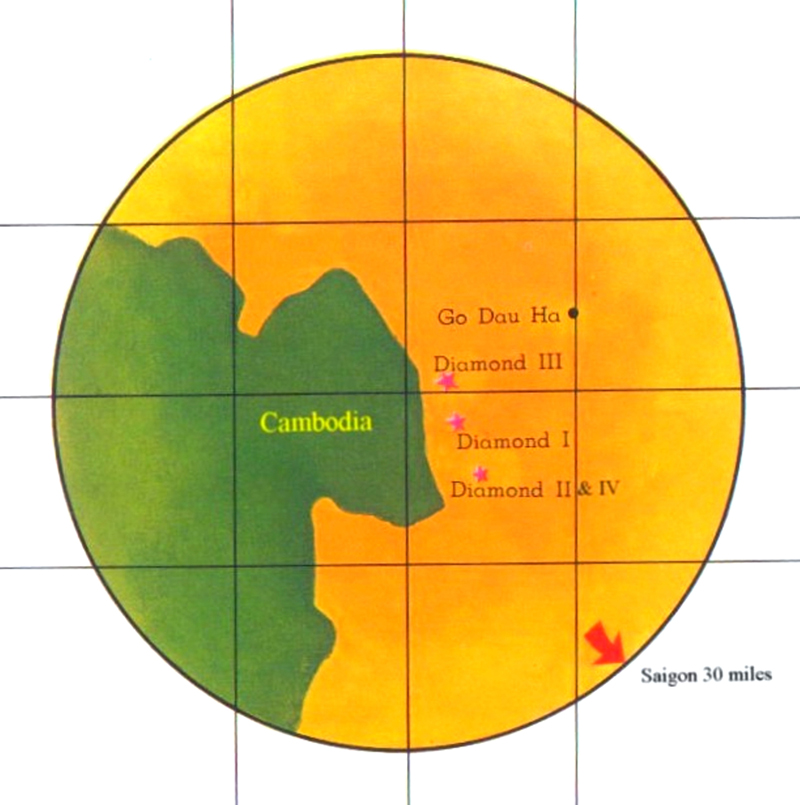

But to return to my tale, the Diamonds were the names given to a series of minuscule bases established by Wolfhounds in the Vietnam War. They were astride the An Ninh corridor, one of the main North Vietnamese resupply routes. They were called “patrol bases” There are two good accounts of how and why the bases were built in an earlier story here.

The tactical concept for the Diamonds was devised by Lieutenant Colonel Vincent J. Oddi, commander of the Second Wolfhounds in the last months of 1968 and early 1969. Oddi thought that small patrol bases built close to the border might tempt the enemy to openly attack them, bringing massive U.S. firepower on them. In telephone conversations exchanged with the author years many years later, when Oddi was in retirement in Florida, he said he had tired of the casualties the battalion took in earlier operations, when fighting almost always occurred on the enemy’s terms. The NVA and VC would set ambushes, spring them and then melt into their hiding places, more often than not across the border in Cambodia.

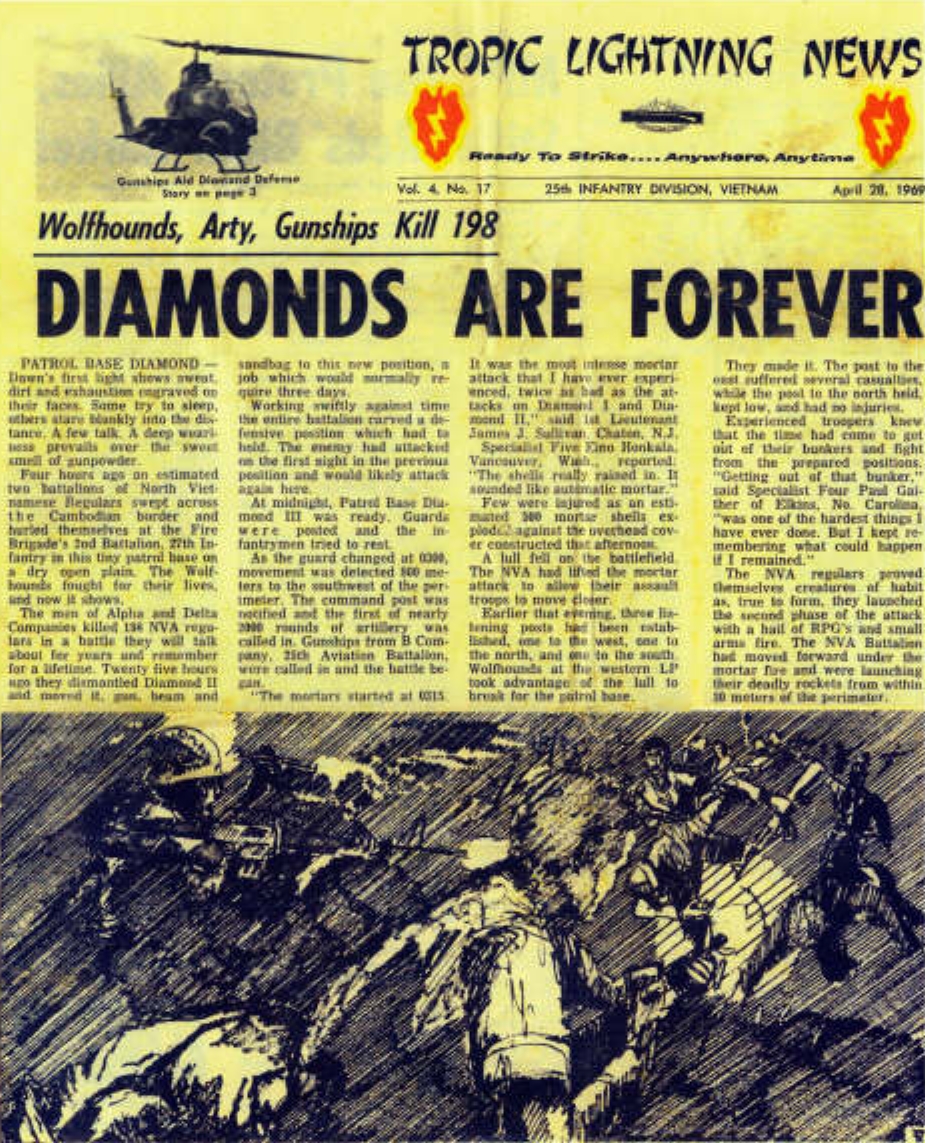

Oddi’s plan worked to perfection. The enemy attacked Diamond I on February 23, 1969 and again on February 25. The attackers’ losses were staggering, when massive artillery fire and airpower battered them. At the time, Major Charles C. Darrell, who was on the 25th Division staff, recorded the events at the division headquarters following the fighting:

“The radar picked up the NVA,” the G-3 reported to General Wiliamson. “The artillery engaged them, and this morning the infantry went out and counted the bodies and policed up their weapons.”

“That’s the way to fight, replied the general. “Use bullets, not bodies.”

The name Diamonds came from the shape of the first of the little bases. It was actually square-shaped, but someone thought calling the shape a diamond made a better name, and he was right. Then a writer at Topic Lightning News, the division newspaper, remembered a song and a name from an old James Bond film called “Diamonds are Forever.” From that day on, the Diamonds were etched in Wolfhound history.

It was dangerous real estate. The battalion continued to work close to the border. One of the later patrol bases was named PB Kotrc, for Captain James Kotrc, who was killed in the fighting at the Bo Bo Canal described in another Tale on this website. As battalion executive officer, I remember a conversation with one of the riflemen about working that close to the border.

“It looks to me like we are bait,” he said. I remembered that, to hunters, the concept is sometimes known as the tethered goat. The aim is not to sacrifice the goat, but to kill the predator that uses it as prey.

On April 14, the patrol base was moved about six kilometers to a new location called Diamond III. The Wolfhounds worked hard on their fortifications until dark. At 3 a.m., the NVA launched a massive attack, overrunning a listening post. The Wolfhounds in the listening post fought to the death, exhausting their ammunition. Again, air and artillery punished the enemy, and the Wolfhounds’ fire stopped them outside the wire.

The square or diamond-shaped configuration of the first Diamond patrol base lasted only ten days. It was a mistake that was not repeated. In the first enemy attack on it, the NVA hit two sides in one corner at the same time, and overwhelmed the defenders. Four bunkers were overrun, and Wolfhounds were killed in all of them.

The rest of the Diamonds were circular, and capable of delivering tightly interlocked and overlapped firepower. They provided no avenues of approach for enemy attack on the positions. But there was never enough preparation time. Paul “Gabby” Gaither, of Company D was at three of the Diamonds. He believes that confusion in the heavy firing caused men to count more incoming rounds than the bases actually sustained. In the short time they had to strengthen their positions before attacks, the wolfhounds had worked hard. But as Gaither said later, “We were never 100 percent ready for them.”

Vince Oddi knew he had to stay ahead of enemy reaction, so he frequently moved the patrol base to a new location. He gave it a new name each time. Diamond II was struck by the enemy on two successive days, April 5 and April 6.

On May 24, Wolfhound Gerald Maddock wrote to his wife at home: “Back at Jackson, Diamond IV is history, gone, no more. Supposed to pull out again tomorrow on another laager, this time, two days and one night, and hope that is all the longer it is. My ass is dragging, we’ve got to get a break soon. The human body can take just so much, and perform so long under such conditions. Heat casualties have become an almost every day occurrence lately. If it isn’t clouded over during the day, the sun kicks our young asses, and the old ones too. It rains at least once a day, and sometimes, two or three times. And it isn’t very pleasant laying out in the damned rice paddy all night soaked to the bone waiting for Charlie to stroll by on his way to setup a mortar tube, raid a village, or set some more booby traps. Only 146 days to go.”

It was over. The fighting was costly to the Wolfhounds. Altogether 36 men were killed in action in the Diamonds, including four men from Battery C, 1st Battalion, 8th Artillery. Headquarters Company lost two men; Company A had 13 KIAs; Company B had one man killed; Company C lost eleven men; Delta Company lost five. As bloody as it was, the enemy lost many more men. Collectively, estimates by various units were grossly exaggerated, but the Wolfhounds who picked up the weapons of the dead NVA, and searched their bodies for intelligence information saw how effective their firepower had been. Some Wolfhounds pinned ribbons from enemy uniforms to their jungle hats.

Some of the men in the Second Wolfhounds called the battalion commander “Sky” Oddi. But he was quick to get on the ground. It was his habit to jump out of a Command and Control helicopter even before it touched down, with one arm held out for an RTO to thrust the handset of the command net radio into it. Like all fine infantry battalion commanders, he wanted to judge a situation with his own eyes, if possible, before committing his units to a new course of action. Eventually, it would end his command of the battalion.

Soon after the heaviest fighting at the diamonds, Lieutenant Colonel Oddi lost a foot and part of his leg to an enemy booby trap, and the Wolfhounds lost a superb battalion commander. In this writer’s opinion, he was the finest tactical innovator to serve in the Second Wolfhounds in the Vietnam War. Some of his ideas were still being used by commanders and operations officers when the battalion was withdrawn from the border in 1970. Institutional memory in combat infantry battalions is a fragile thing, but the use of the little “hard spots” continued as long as the Second Wolfhounds worked close to the border.

When the Wolfhound battalions air-assaulted into Cambodian territory in 1970, it was payback time. The NVA supply, medical service and technical services troops manning their Cambodian bases ran like rabbits. Few were killed or captured. After our return to Vietnam, the area of operations assigned to the Wolfhound battalions was equal in size to the brigade AOs of earlier days.

But while in Cambodia, we captured and destroyed bases the enemy had run to after nearly every fight, to rebuild his strength and rearm and reequip. There was so much rice captured that little thought was given to evacuating to Vietnam. The preferred way of destroying it was breaking open the sacks, dousing the rice with diesel fuel and setting it on fire. “Diesel-flavored puffed rice,” explained one Wolfhound. Whole hospitals were captured. Tons of weapons, munitions, clothing, and complete maintenance and repair shops were inside the supply dumps. Larger pieces of equipment were transported to South Vietnam. Other things were destroyed in place. I watched a demolition man wire the bicycles from an NVA message center with blocks of explosive C-4, and detonation cord.

As I saw a Wolfhound break open a wooden crate of Chinese-made pistols to pass out to his friends, he looked up at me and said, “Wouldn’t 'Sky' Oddi have enjoyed this?" I nodded, and then thought about some of the other men who would have been sharing the moment if their luck had held. The names of the men who died in the Diamonds were still in a folded typewritten list in my green pocket notebook. I took it out and read down the list, trying to visualize all of the faces. I could remember many of them. Now and then, one of the names would arouse a special pang of regret. Once I got a flash of memory of a smiling, tanned face in a starched khaki uniform I had last seen when he was on his way to Bangkok or some other R and R vacation. I could remember someone opening a can of c-rations, or doing one of a hundred things that Vietnam War infantrymen did every day. My eye caught the name of David Gamboa on the list. I thought of his enthusiasm, and remembered his Mohawk haircut from a photo a stand-down in Cu Chi not long before his death. He had been hamming it up and having a great time. Suddenly, the Cambodia victory didn’t seem like such a big deal. At that moment, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

(Editor’s note: Complete lists of Wolfhounds and artillerymen killed in action in the Diamonds can be found on the Internet pages of Gary Assell, Gerald Maddock, and others.)

Copyright 2011 by Howard Landon McAllister