The Vam Co Dong – A Watery Highway

by Howard Landon McAllister

On a dank, humid evening in 1969, minutes after after a river patrol boat put us ashore on a strip of dry land on the edge of the Vam Co Dong, a Wolfhound turned to me and said, “I grew up in Kansas. Seeing this much water would have scared me to death back then.” I understood. Growing up in Southwestern Virginia, except for the broad New River, I could swim across most streams in a few strokes. We had both been thrust into an environment as alien as a moonscape, and there was nothing to be done except make the best of it.

Today, I remember nothing of what happened that night, but at the time, I wrote the details of in a pocket notebook, and later transcribed the information into records that are still in my files. Most of the men had mixed feelings about officers from the battalion headquarters accompanying them on ambushes. There was a good reason for their attitude. On a positive note, they welcomed the presence of an additional radio on the battalion command net with the ability to provide artillery support within seconds. The presence of outsiders tends to break up the automatic habits that promote quick response to unforeseen events, so it is largely negative. But it was inescapable in that time. Infantry officers of that day were taught the slogan of Gen. Bruce Clarke—“a unit does well only the things the boss checks.” Few battalion operations officers of the Vietnam War who had been company commanders earlier in the war would resist the temptation to make the checks. I confess to being among them.

That night, for me, things had gone wrong from the beginning. Danny Klossner, the radio-telephone operator who had accompanied me, had twisted his ankle when he stepped off the patrol boat. I decided to carry his radio myself, and sent him back on the boat. Later, when we were settling into our ambush position, I remembered that all of the magazines for my CAR-15 were filled with tracer rounds, which were perfect for marking targets from a helicopter, but nothing could be worse in an ambush position, as they would mark the firer’s position.

I asked the soldier next to me if I could borrow a couple of magazines from him. I could not see his face in the dark, but it was just as well. “Major, if you are going to come out here like this with us, you need to get your shit together a little better,” he said, as he handed me the magazines.

The patrol leader was a young sergeant, but he had plenty of experience at what we were doing that night. For one thing, he knew the coordinates picked out for the location by the battalion operations section were nothing more than a location where recent enemy activity had been reported. The mission of the ambush patrol was to locate itself somewhere close to the site and to wait and see if anything turned up. More often than not, there was no contact with our enemy. That was not an issue with most of the patrol members. They knew that even a successful ambush with casualties inflicted on the enemy would require a search of the area the following morning, and wounded enemy soldiers who were trapped there would be far more dangerous than those who might escape being killed or captured.

By sound and touch more than sight, the patrol leader had set us up on the edge of a broad canal about fifty meters from where the canal joined the river. The site was muddy and waterlogged, but we settled in. Mosquitoes were already fierce. Poncho liners eased the bite of the chilly dampness, but not very much. We spent the night in physical misery, but without incident.

At first light, every man was alert. When we looked around us, nothing appeared as we had imagined it in the darkness. A dense, towering clump of bamboo stood nearby. Only the top of it had been visible against the night sky a few hours before. As we waited for the boats, we opened c-ration cans and made instant coffee warmed with heat tabs or bits of C-4 explosive lit with a match or cigarette lighter. It was just another day in Vietnam.

The two Wolfhound battalions learned how to operate in the humid, treacherous environment, but the experience was marked by the loss of many lives. Ambush patrols expect that men moving into their line of fire at night will be the enemy, but it was not always the case. Small reconnaissance patrols sometimes became disoriented, or were not in radio communications with the ambush patrols, and Americans were killed by other Americans.

In one sense, the river was a highway for all of the combatants in the war. The U.S. Navy operated two bases in the Wolfhounds area of operations. One was a large facility built near one of the old triangular French forts at Tra Cu and the other was located on the West bank of the Vam Co Dong at Go Dau Ha, at the bridge on Highway 1.

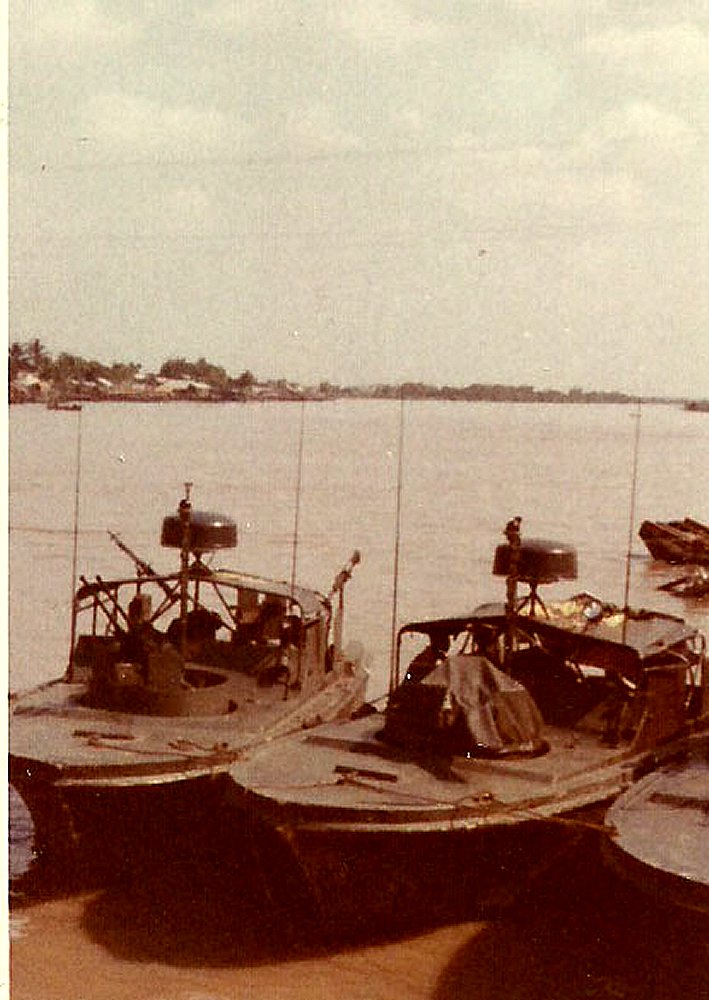

During the Vietnam War, the U. S. Navy had a force known as the “brown water navy,” using fast, lightweight, and lightly armed patrol boats called PBRs. The PBRs operated out of small riverside bases, with a complex system of larger vessels for repair and support, including fire support and troop housing on large barges that had to be towed into positions and anchored. Many of the support vessels were relics of World War II, retrofitted at incredible expense by Navy bureaucrats. A modern air force would have made a shambles of them, and they suffered more than a few indignities from primitive North Vietnamese weapons, from rocket propelled grenades on up. But Wolfhound infantrymen appreciated support from the PBRs. The .50 caliber machine guns they carried were powerful weapons in that environment.

Most Wolfhounds were familiar with the PBR base located on the western side of the Go Dau Ha bridge over the Vam Co Dong. It was many things to many Wolfhounds. It was a place to spend the night when traveling by jeep or truck from the western side of the river to Cu Chi. It was also a place to trade captured war trophies for cases of frozen steak and lobster tail. It was a place to enjoy a drink together after days of tense, dangerous field operations. In short, it was an oasis in a watery desert.

For all of the perils and physical discomfort of the river and river operations, most Wolfhounds preferred it to the nerve-wracking danger of moving on foot across rice paddies framed by hedgerows, with endless artfully camouflaged booby-traps. It is a choice that most Vietnam War Wolfhounds would have no desire to make today.

Copyright 2011 by Howard Landon McAllister