Wolfhound Commanders II: Yellowhair Rides Again

by Howard Landon McAllister

When you're assigned to the Wolfhounds, you start to hear the names of legend like "Iron Mike" Michaelis, and Lew Millett, who led the last bayonet charge in the Korean War, perhaps the last in American military history. Vietnam had its own legendary figures – from August 1969 on, every man in the Second Wolfhounds knew about "steel pot" Rittgers, the battalion commander, who, after being painfully wounded, battered an enemy soldier to death with his steel helmet in a desperate struggle in a shell crater at the Bo Bo Canal. His wounds put him in the hospital, but he later returned to the division and served as commander of the 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry (Manchus). He tells the story of attending a division staff briefing after he returned, where he discovered that someone, thinking he had been killed, had named a patrol base for him. In the style of Mark Twain, he reminded them that rumors of his death had been premature.

Other Wolfhounds remember Major Sandy Meloy of the First battalion of the Wolfhounds, earlier chronicled in these pages, to be followed later by others. I never served with these officers, but I served with two of the best in 1970.

One of them was himself the descendant of an American military legend.

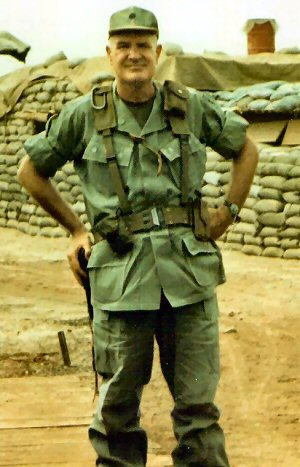

The first time I ever saw the command style of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer III, or perhaps I should say heard – he was making a loud pronouncement about something that had gone wrong in the Tactical Operations Center at Fire Support Base Jackson. I knew it was going to be a rough day. I had just followed the colonel into the fortified bunker after chewing out a Wolfhound near the helipad.

"So that's Yellow Hair," the man had said, after the Colonel had passed. I stopped and got in his face.

"What did you say, Wolfhound?"

"Somebody told me he was the grandson of General Custer, sir – and they used to call HIM Yellow Hair, or something like that."

I had to stifle a laugh. It was a good thing the colonel had been wearing his helmet. He didn't have much more hair on his head than Telly Savalas, the movie actor.

"Let me tell you something," I said. "This colonel is a badass. He hasn't got a hair on his head – he shaves it every night with a bayonet. Can you imagine how it would piss him off to hear you call him Yellow Hair?"

It didn't do any good. The name was just too appealing for the soldiers to forget it. Even the division newspaper played on Custer's name, linking it with that of a Tropic Lightning soldier who was a full-blooded Sioux whose Indian name was Chasing Horse.

I don't remember him ever talking about his famous Civil War ancestor, but there was no doubt where his loyalties would have been. One day he was flying over a Delta Company position, and he radioed the company commander, "Remove that flag from your radar tower. It's been obsolete since 1865!" Down came the Confederate flag. When the colonel got back to Fire Support Base Jackson, Major Charles "Butch" Darrell told him he had a Confederate flag at home that had been carried into battle by the ARVN 4/45th Infantry when he was their advisor. Custer turned on him instantly, "I hope it reminds you every time you look at it that we kicked your ass thoroughly, completely, and permanently."

He WAS a badass, and he was fearless – and I loved him. He was brusque, and unflinchingly honest, but there was a fatherly element in his manner, however hard he tried to conceal it. Butch Darrell and I, as the only two other field-grade officers in the battalion, were his closest confidants. He was closer to Butch than to me and always called him "you sonofabitch." In a way, I was a little jealous because he never called me that, and I recognized it as a term of endearment. He was rough, but he was not insensitive. One time, while we were waiting for a helicopter, he said, "Butch and Dutch – sounds like I inherited a goddam Vaudeville show." Then he put his arm around my shoulder, and said in his gravel voice, "but you two are my lions, and I am lucky to have both of you."

He always set the example, and we would have followed him anywhere. Major Darrell remembers an incident that set us apart from some of the other battalions:

"All right, you sonofabitch," Custer said, "Something's wrong. The Triple Deuce (2d Battalion, 22d Infantry) reports initiating 98 percent of their fights. We initiate less than half. Colonel Smith is angry. He says the enemy has the initiative in our area and that looks bad. I want you to fly over to the Triple Deuce and find out how they are reporting."

When Major Darrell arrived at the Triple Deuce fire support base, he met an old acquaintance, a sergeant who had worked for him at Fort Polk prior to their Vietnam days.

"How are you guys managing to report 98 percent friendly-initiated actions?"

'It's all hogwash," the sergeant replied. "Last night, one of our foot patrols hit a booby-trap. One man was killed and two were wounded. We never saw the enemy, but we reported we had initiated the action."

A Triple Deuce major joined them. He was a year behind Major Darrell at West Point, but they did not know each other.

"Sergeant Hudnell and I are old friends. He told me about last night's action. How were you able to report that your patrol started the fight?"

The other major was a brave and good officer, and he understandably took offense.

"There would have been no fight," he replied, "If we had not sent out the patrol."

"What does the enemy have to do to get credit for starting a fight? By your reasoning, we start every fight, because none of this would have happened if the US hadn't intervened in the first place."

"Don't be so stupid," replied the Triple Deuce major. "You know how the system works. If your battalion commander hopes to be promoted, he'd better report that his troops are initiating the action and not just reacting to the enemy."

"Colonel Custer doesn't expect to be promoted," Major Darrell answered, "so it's all right for him to tell the truth."

But Custer was a realist, and he knew what would eventually happen in Vietnam. He told us on more than one occasion that we would eventually pull out of Vietnam and that the enemy would take over. He saw the grim mathematics of war as a waste, whether we won or not. He told Butch Darrell every life lost was a life wasted. "Some mother loses a son, some wife loses a husband, some child loses a father. Win or lose, every single death is a waste. Our job is to make sure that not one soldier dies because of our failure to fight as hard and as well as we can."

He was a Good Samaritan to the Vietnamese on many occasions. Once after he had flown into an unsafe village to pick up and fly a sick child and its mother to a hospital, I got as close as I ever came to chewing him out.

"Colonel, you're going to get yourself killed, flying into places like that village in this unarmed loach. You've got to stop doing this stuff."

He nodded, almost contritely, then turned on me, "You can't talk to me like that! I'm your commander," he said with a grin. I just shook my head and walked away from the helipad.

He was absolutely fearless, and his curiosity led him into harm's way at every turn. But he was lucky, too. I can't imagine how he could have exposed himself to enemy fire as many times as he did without getting killed or wounded. The Renegade Woods battle in early April of 1970 was the most important engagement of the entire year for the Second Wolfhounds, and at no other time were we as heavily engaged. Three companies of the battalion (A, B, and C) and two companies of the 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry (Triple Deuce) under our operational control fought two well-entrenched battalions of the 271 Regiment, 9 VC/NVA Division. I took command of our units on the ground, and Colonel Custer spent the next five days in the air over the battlefield, engaging in non-stop heroics. In the best tradition of his cavalry ancestor, he played Sky Warrior, dropping flame-baths and grenades from the Command and Control helicopter, hanging out of the open door, marking enemy positions with tracers using the Sergeant Major's M-16. I never learned how many hits the C&C helicopter took during the battle, but it must have been a considerable number.

I remember the voice of Captain Wendell Brown, one of the Forward Air Controllers (who was killed a few weeks later while supporting us) coming over the radio, in flat incredulous tones, "What...is...he...doing...now?" I think it was in his genes. He was competing with his ancestor. Yellow Hair rides again.

He was always combative. Once I remember a disagreement he had with the commander of another battalion during a meeting to plan a joint operation. He got red in the face and drew back his arm. I was sure he was about throw a punch at the other officer. Standing behind him and to the side, I was able to grab a handful of fatigue shirt. It defused the situation. Custer turned on me, flashed me the sunniest grin you ever saw, then wheeled and walked out of the room, with those pale eyes blazing.

I never saw him again after the war. He retired from the Army as a full colonel and died in 1991 of a heart attack at the age of 67.

© 2000, Howard Landon McAllister

photo of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer III courtesy of BG C.M. Agena, USA, ret.